How Should Investors Forecast Earnings Growth

Post on: 17 Июль, 2015 No Comment

Unless you’re a deep value / bargain investor focused on buying £1 worth of assets for 50p. a company’s future growth rate is likely to be of some interest to you. Whether you are doing a DCF valuation. or simply trying to figure out what the PEG ratio looks like, forecast growth is a key input to help determine your target price or stock selection criterion. So what are the options for good and reliable forecasting? To get wiser in this area, it’s definitely worth taking a close look at Professor Damodaran’s The Dark side of Valuation (available on Amazon). He’s by far the clearest thinker we’ve come across in this space and, in broad terms, he argues that there are two easy but bad ways to forecast (i.e. relying on the past or other people) and one good but hard way (i.e. forecasting from fundamental determinants).

Can you trust the past?

The first thing that investors tend to do when forced to consider the future is to look at the past. Unfortunately, this is an approach that is likely to lead nowhere in terms of forecast accuracy for a number of reasons. First, historical growth rates tend to involve considerable noise — this is especially true of earnings due to the number of adjustments involved versus sales. In a famous study, Little (1960) coined the term ‘Higgledy Piggledy Growth because he found almost no evidence that firms that grew fast in one period continued to grow fast in the next period. In addition, historic growth measurement is not straightforward — rates may be complicated by the presence of negative earnings, or they may differ greatly depending the period or methodology selected (e.g. an arthmetric average, a geometric average, a log-linear regression model or more sophisticated statistical techniques like time-series models). Even time-series models (despite requiring a lot of historical data) don’t seem to be that accurate if you’re looking to forecast over longish time-periods.

Can you trust the management?

If not the past, how about the revenues and earnings forecast provided by the company management? While this practice has the advantage of simpliciity or indeed laziness, it is also flawed. The main issue is bias — clearly, company management are not going to be neutral about the company’s future prospects and their own skill. Management forecasts may represent wish lists, or alternatively management may play down expectations if their compensation is tied to beating the forecasts provided. Finally, management forecasts can be inconsistent (e.g. by assuming revenue growth of 10% a year for the next 10 years but with little or no new capex over the period). While there is clearly useful information in these management estimates, it needs to handled with care and an independent perspective that checks for internal consistency.

Can you trust the analysts?

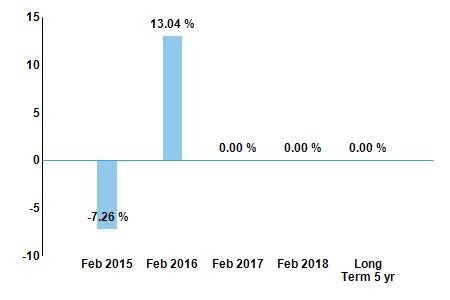

So if neither of those approaches work, what about trusting analysts that follow the firm to come up with the right growth estimate? Unfortunately, the evidence suggests that analysts are hopeless forecasters, especially over the long-term. Analysts often make significant errors, either by relying on the past (see above), using erroneous or misleading data sources or by overlooking significant shifts in a firm’s prospects. Furthermore, when managers provide forecasts, analysts usually jump at the opportunity by arguing that managers know more about the company than they do without recognising the bias issues mentioned above.

David Dreman discusses the appalling track record of analyst forecasting in his book, Contrarian Investment Strategies. More recent work by James Montier found that:

In the US, the average 24-month forecast error is 93%, and the average 12-month forecast error is 47% over the period 2001-2006. The data for Europe are no less disconcerting. The average 24-month forecast error is 95%, and the average 12-month forecast error is 43%. To put it mildly, analysts don’t have a clue about future earnings.

According to Damodaran, the general consensus is that analyst forecasts are better than extrapolating from historical growth over the very short-term (up to 1 year) but not over longer time frames. He suggests several factors/questions that can help determine the weight assigned to analyst forecasts:

- How much recent firm-specific information is there? Have there been significant changes in management or business conditions in the recent past, for example, a restructuring?

- How many analysts follow the stocks? Generally speaking, the more there are, the better informative the consensus (although there is also a risk of herding)

- What much disagreement is there? Because of this herding phenomenon, the extent of disagreement between analysts, for example measured by the standard deviation in growth predictions, is also a useful measure of the reliability of the consensus forecasts.

- Quality of analysts following the stock (although this can be difficult to judge in many cases).

The Answer: Listen to the Business Fundamentals

Given the inherent limitations of these approaches, Damodaran suggests another interesting approach which leverages the Sustaintable Growth Model. Rather than treating growth as being divorced from the operating details of the firm, he argues that it’s better to make it endogenous, i.e. to make it a function of how much a firm reinvests for future growth and the quality of its reinvestmen t.

He points out that the expected growth in operating earnings for a stable firm should be a product of the reinvestment rate (the proportion of after-tax operating income that is reinvested back into new assets) and the return on capital the firm makes on its investments:

Expected growth in EBIT = Reinvestment Rate * ROC.

In the same way, growth in earnings per share or net income is a function of the proportion of net income that is invested back into the business (the retention rate), and the return made on just the equity investment (the return on equity):

Expected growth in Earnings = Reinvestment Rate * Return on Equity.

So if the company’s retention rate is 20% and its return on stockholders’ equity is projected to be 25%, then its growth for the coming year should be 5%.

He argues that forecasting this way is useful at two levels: firstly, it recognises that growth is never costless, i.e. to grow faster, you have to reinvest more, which means less is available for dividends. Secondly, it allows you to distinguish between growth that creates value vs. that which destroys value. Of course, this approach then just creates the problem of having to estimate a company’s reinvestment rates and marginal returns on equity and/or capital in the future. While this is difficult to do, the point is — how can growth-based valuation to be meaningful without first thinking hard about the firm’s reinvestment policy and its return rates? As Damodaran notes:

I do not see how any company can be valued without making assumptions about these variables. Note that those who use analyst or historical growth rates are implicitly assuming something about reinvestment rates and returns, but they are either unaware of these assumptions or do not make them explicit.

Don’t Forget Mean Reversion

Finally, whether considering growth rates on their own, or the fundamental determinants of growth like ROE, it’s critical to factor in mean-reversion. Mean-reversion refers to the fact that above average performance tends not to last. The human tendency is to look at fast-growth firms and wrongly assume that they are inherently fast-growth firms or vice versa — this is an example of “anchoring bias” where we overweigh the significance of recent observations when forming expectations about the future. It also ignores the competitive pressure which is at the heart of the capitalist system.

Even for a stellar company, the growth rate cannot forever be higher than the GDP growth rate. In the US, historic GDP growth has been 5.3% from 1790 to 2010 and 6.6% from 1945 to 2010. Even these numbers may be optimistic if the US economy itself mean-reverts! One piece of research, based on five decades of data, showed that only 10% of large U.S. companies had increased their earnings by 20% for at least five consecutive years. only 3% had grown by 20% for at least 10 years straight, and not a single one had done it for 15 years in a row . According to Montier, most studies show mean reversion in profitability at around 30% to 50% a year.

We will be building some of this thinking on forecasting into Stockopedia Premium (learn more here ), so any comments are of course welcome!