What Is Quantitative Easing Defined and Explained

Post on: 30 Август, 2015 No Comment

How Central Banks Create Massive Amounts of Money

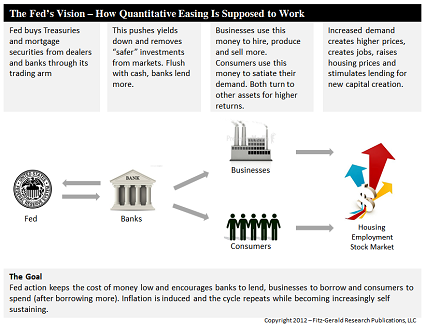

Definition: Quantitative easing (QE) is a massive expansion of the open market operations of a central bank. The bank buys securities from its member banks to add liquidity to capital markets. This has the same effect as increasing the money supply. In return, it issues credit to the banks’ reserves to buy the securities.

Where do central banks get the credit to purchase these assets? They simply create it out of thin air. Only central banks has this unique power. It has the same effect as printing money.

The purpose of this type of expansionary monetary policy is to lower interest rates and spur economic growth. Lower interest rates allow banks to make more loans. Bank loans stimulate demand by giving businesses cheap loans to expand, and shoppers more credit to buy things with.

By increasing the money supply, QE keeps the value of the country’s currency low. This makes the country’s stocks seem like a relatively good investment to foreign investors, and makes its exports relatively cheaper.

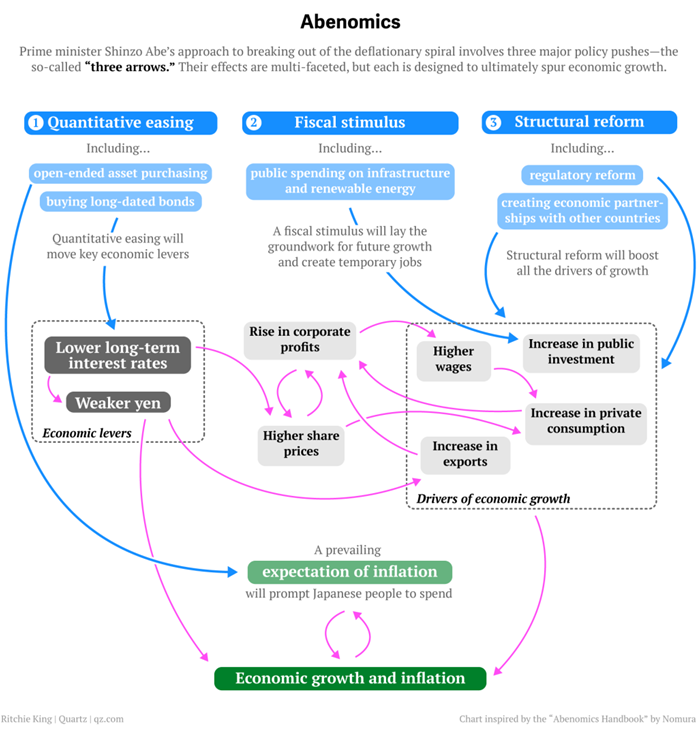

Japan was the first to use Quantitative Easing, from 2001 to 2006. It restated in 2012, with the election of Shinzo Abe as Prime Minister. For more, see Japan’s Economy .

The European Central Bank adopted QE in 2014, after seven years of austerity measures. It will purchase in an attempt to lower the value of the euro, which has already dropped. For more, see Euro to Dollar Conversion History .

However, the most successful QE effort was undertaken by the U.S. Federal Reserve. As a result, its balance sheet more than quadrupled, from $2.825 trillion in 2008 to $4.482 trillion in 2014. That makes the U.S. QE the most massive economic stimulus program in world history.

Federal Reserve Quantitative Easing Explained

How does quantitative easing work? The adds credit to the banks’ reserve accounts in exchange for MBS and Treasuries. The asset purchases are done by the Trading Desk at the New York Federal Reserve Bank.

The reserve account is the amount that banks must have on hand each night when they close their books. The Fed requires that around 10% of bank deposits be held either in cash in the banks’ vaults or at the local Federal Reserve bank. For more, see Reserve Requirement .

When the Fed adds credit, the banks have more than they need in reserves. They now have more to lend to other banks. As banks try to unload their extra reserves, they drop the interest rate they charge. This is known as the Fed funds rate. This rate is the basis for all other interest rates. (Source: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, What are the tools of U.S. monetary policy? )

Quantitative easing stimulates the economy in another way. The Federal government auctions off large quantities of Treasuries to pay for expansionary fiscal policy. As the Fed buys Treasuries, it increases demand, keeping Treasury yields low. Since Treasuries are the basis for all long-term interest rates. it also keeps auto, furniture and other consumer debt rates affordable. The same is true for corporate bonds. allowing businesses to expand more cheaply. Most important, it keeps long-term, fixed-interest mortgage rates low. And that’s important to support the housing market.

Even before the recession. the Fed held between $700-$800 billion of Treasury notes on its balance sheet. varying the amount to tweak the money supply.

QE1 (December 2008 — June 2010)

On November 25, 2008, the Fed announced it would purchase $800 billion in bank debt, U.S. Treasury notes and mortgage-backed securities (MBS) from member banks. The Fed created quantitative easing to combat the financial crisis of 2008. It had already dramatically lowered the Fed funds rate to effectively zero. For more, see Current Fed Interest Rates.

Its other monetary policy tools were also maxed out. The discount rate was near zero. The Fed even paid interest on banks’ reserves.

By 2010, the Fed bought $175 million in MBS that had been originated by Fannie Mae. Freddie Mac. or the Federal Home Loan Banks. and $1.25 trillion in MBS that had been guaranteed by the mortgage giants. Initially, the purpose was to help banks by taking these subprime MBS off of their balance sheets. In less than six months, this aggressive purchasing program had more than doubled the central bank’s holdings. Between March and October 2009, the Fed also bought $300 billion of longer-term Treasuries, such as 10-year notes .

The Fed halted purchases in June 2010 because the economy was growing again. Just two months later, the economy started to falter, so the Fed renewed the program. It bought $30 billion a month in longer-term Treasuries to keep its holdings at around $2 trillion. For more, see QE1.

QE2 (November 2010 — June 2011)

On November 3, 2010, the Fed announced it would increase quantitative easing, buying $600 billion of Treasury securities by the end of the second quarter of 2011. For more, see The Federal Reserve’s Quantitative Easing 2 .

Operation Twist (September 2011 — December 2012)

In September 2011, the Fed launched Operation Twist. This was similar to QE2, with two exceptions. First, as the Fed’s short-term Treasury bills expired, it bought long-term notes. Second, the Fed stepped up its purchases of MBS. Both twists were designed to support the sluggish housing market. For more, see What Is Operation Twist? .

QE3 (September 2012 — October 2014)

On September 13, 2012, the Fed announced QE3. It agreed to buy $40 billion in MBS, and continue Operation Twist, adding a total $85 billion of liquidity a month. The Fed did three other things it had never done before:

- It announced it would keep the Fed funds rate at zero until 2015.

- It said it would keep purchasing securities until jobs improved substantially.

- The Fed acted to boost the economy, not avoid a contraction. (Source: CNBC, Three Things the Fed Did Today It’s Never Done Before. September 13, 2012)

QE4 (January 2013 — October 2014)

In December 2012, the Fed announced it would buy a total of $85 billion in long-term Treasuries and MBS. It ended Operation Twist, instead just rolling over the short-term bills. It clarified its direction by promising to keep purchasing securities until one of two conditions were met: either unemployment fell below 6.5% or inflation rose above 2.5%. Since QE4 is really just an extension of QE3, some people just refer to it as QE3. Other refer to it as QE Infinity because it didn’t have a definite end date. For more, see QE4 .

News

On December 18 2013, the FOMC announced it would begin tapering its purchases, as its three economic targets were being met: The unemployment rate was at 7%, GDP growth was at least 2-3%, and the core inflation rate hadn’t exceeded 2%. The FOMC would keep the Fed funds rate and the discount rate between zero and 1/4 points until 2015, and below 2% through 2016.

Sure enough, on October 29, 2014, the FOMC announced it was ending its purchases. Its holdings of securities had nearly doubled from $2.825 trillion to $4.482 trillion, It would continue to replace these securities as they came due to maintain its holdings at current levels. (Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Financial Crisis Timeline ; Federal Reserve. Open Market Operations )

The Fed planned to raise interest rates in mid-2015, if the economy continued to improve. At that time, it would gradually reduce its QE holdings by not replacing them once they matured. For the latest updates, see FOMC Meetings.

Did Quantitative Easing Work?

QE achieved some of its goals, missed others completely, and created several asset bubbles. First, it removed toxic subprime mortgages from banks’ balance sheets, restoring trust and therefore banking operations. Second, it also helped to stabilize the U.S. economy, providing the funds and the confidence to pull out of the recession. Third, it kept interest rates low enough to revive the housing market. Fourth, it did stimulate economic growth, although probably not as much as the Fed would have liked.

However, it didn’t achieve the Fed’s goal of making more credit available. It gave the money to banks, which basically sat on the funds instead of lending it out. Banks used the funds to triple their stock prices through dividends and stock buy-backs. The large banks also consolidated their holdings, so that the largest .2% of banks now control more than 70% of bank assets.

That’s why QE didn’t cause widespread inflation. as many feared. If banks had lent out the money, businesses would have increased operations and hired more workers. This would have fueled demand, driving up prices. Since that didn’t happen, the Fed’s measurement of inflation, the core CPI, stayed below the Fed’s 2% target. (Source: WSJ, Confessions of a Quantitative Easer. November 12, 2013)

Instead, QE created a series of asset bubbles. In 2011, commodities traders turned to gold, driving it price per ounce from $869.75 in 2008 to $1,895. In 2012, investors turned to U.S. Treasuries, driving the yield on the 10-year note to a 200-year low.

In 2013, investors fled out of Treasuries and into the stock market, driving the Dow up 24%. This followed Ben Bernanke’s announcement on June 19 that the Fed was considering tapering. This threw bond investors into a panicked selling spree. As demand for bonds fell, interest rates spiked 75% in three months. As a result, the Fed held off the actual taper until December, giving the markets a chance to calm down.

In 2014, the value of the dollar rose 15%, as investors created a bubble in that asset. This is the opposite of what’s supposed to happen with QE. However, the U.S. dollar is a global currency, as well as a safe haven. Article updated February 1, 2015.