Using an Optimal Capital Structure in Business Valuation

Post on: 26 Сентябрь, 2015 No Comment

There is little question that the capital structure that a company’s management puts in place affects the company’s risk profile, the cash flows that are ultimately available to equity investors, and, consequently, the returns achieved by those investors.

It is also fairly well accepted that, when valuing a minority or non-controlling interest in a company under the fair market value standard, the company’s actual capital structure should be utilized by an appraiser when determining that company’s weighted average cost of capital (WACC). That is because a non-controlling owner would not have the ability to implement a change in the capital structure. The question is whether, under the fair market value standard, an actual or hypothetical capital structure should be utilized when valuing a controlling interest in a company.

During the course of our analysis, we often encounter companies that have little or no debt, even though they are generating significant cash flows that could be used to service a reasonable amount of debt, and the owners may be proud of their debt-free status. What these owners don’t understand is that, while the lack of debt certainly reduces the risk of owning an equity investment in that company, it also reduces the returns that are realized by the owner. This is where an appraiser has to remember that, under the fair market value standard, the owner of the company is a hypothetical owner, and a hypothetical owner does not avoid debt based on his or her personal risk tolerances.

We believe that, with minor exceptions, when valuing a controlling interest in a company under the fair market value standard, it is appropriate to utilize a hypothetical (or optimal) capital structure. This is because a controlling owner would have the ability to put an optimal capital structure in place, whereas a minority owner would not have such ability.

By implementing an optimal capital structure, a hypothetical owner tries to maximize returns without incurring undue risk. In addition, using an optimal capital structure when valuing a controlling interest avoids one of the biggest drawbacks created when using an actual capital structure in the appraisal of a business: that a company’s actual capital structure will frequently change as the market value of its equity changes and debt securities are issued and retired. Therefore, on a given day the company’s capital structure may not fairly represent management’s targeted capital structure, since making changes in capital structure can be a significant and lengthy endeavor.

Estimating the Optimal Capital Structure

There are several ways in which to estimate a company’s optimal capital structure. One way is to assume that other companies in the industry are operating at or near their optimal capital structures and to obtain published industry statistics from sources such as Ibbotson Associates’ Cost of Capital. While useful in some cases, these industry statistics are conglomerates of data and often include companies that are not sufficiently similar to the subject company. Also, the time frame in which the data was collected may be unclear or may not be in reasonable proximity to the date of valuation.

For these reasons, published industry statistics alone many not provide a meaningful or accurate measure of an appropriate capital structure. In the following paragraphs, we describe three other methods for estimating an optimal capital structure of a company.

Method One: Utilizing Guideline Companies. One way to estimate the subject company’s optimal capital structure is to utilize the average or median capital structure of the guideline companies employed in the market approach.

This approach is useful because the appraiser is well aware of which companies are included in the analysis and the degree to which they are similar to the subject company. The drawback is that, again, fluctuations in market prices and the staggered nature of debt offerings and retirements may cause the actual capital structure of a guideline company to be substantially different than its target capital structure. This issue is mitigated somewhat when numerous guideline companies exist and it becomes more likely that an average or median capital structure truly reflects an optimal capital structure.

Unfortunately, in many valuation engagements the subject company is relatively unique and the appraiser is unable to find publicly traded companies that are comparable. In these cases, it may be necessary to rely on methods that focus on the specific characteristics of the subject company.

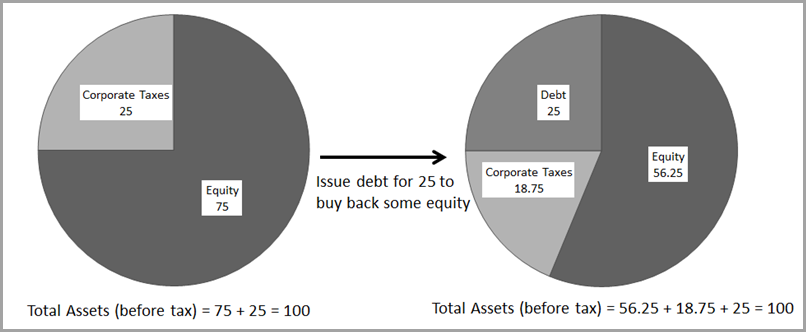

Method Two: Lending Guidelines. If the risk of a company did not change due to the nature of its capital structure, a company would want as much debt as possible, since interest payments are tax deductible and debt financing is always cheaper than equity financing.

The reality, however, is that a company’s risk profile does increase as more debt is added, since the company’s debt coverage ratios deteriorate and its ability to survive a downturn shrinks. Therefore, the required rates of return for both debt and equity holders increase as debt is added, since investors require additional returns to compensate for the increased risk.

The objective of the business valuation professional is to determine the level of debt at which the benefits of increased debt no longer outweigh the increased risks and potential costs associated with a financially distressed company.

Because a company would want to maximize the amount of leverage in its capital structure without incurring undue risk, an appropriate gauge for determining the level of debt is the amount that lenders would be willing to loan to the company. If the subject company’s industry attracts specialty lenders (e.g. franchise restaurants, real estate, etc.), the appraiser may be able to talk to loan underwriters or obtain literature that would indicate the criteria used for making loans.

Shannon Pratt, in his Business Valuation Update. will periodically publish bank lending parameters. For instance, in the October 2001 issue, Total Debt to EBITDA ratios were shown to range from 3.5 to 4.0 times. The appraiser could also speak with local business brokers and M&A advisors to get a feel for the current lending criteria.

The advantage of using lending parameters is their ease of acquisition and their ease of use. However, the disadvantage is that lending parameters are generic, often broad in scope, and may not be applicable to the subject company.

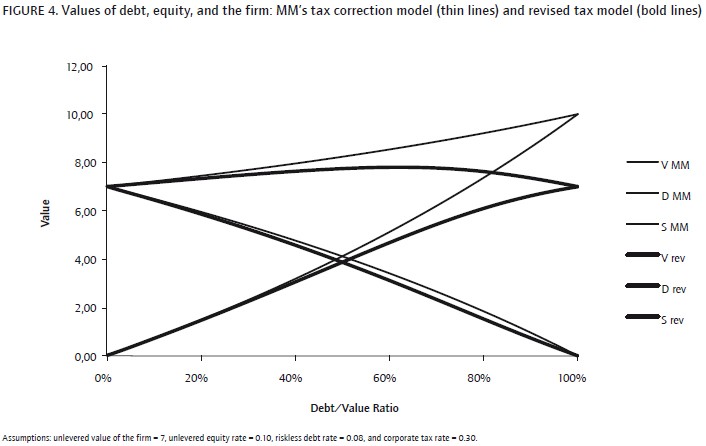

Method Three: Synthetic Cost of Capital Curve. The most complex of the various methods for estimating an optimal capital structure is through the construction of a cost of capital curve. The curve illustrates the company’s weighted average cost of capital at all combinations of debt and equity financing.

Utilizing a Cost of Capital Curve

The most complex of the various methods for estimating an optimal capital structure is through the construction of a cost of capital curve. The cost of capital curve illustrates the company’s weighted average cost of capital at all combinations of debt and equity financing. This approach is discussed in detail by Aswath Damodaran in his book, The Dark Side of Valuation. The methods for estimating the cost of debt and cost of equity as the capital structure changes are described below.

Estimating Cost of Debt for Each Level. The cost of debt measures the current cost of borrowing funds to finance operations. In general terms, a company’s cost of debt is determined by the following variables: the current level of interest rates; the default risk of the company; and the tax advantages associated with debt.

While the company’s cost of debt implied by its current capital structure may sometimes be readily available, estimating the company’s cost of debt assuming different levels of debt in its capital structure is a theoretical exercise. It requires the appraiser to impute a cost of debt at each point on the cost of capital curve.

One way to estimate a company’s cost of debt at various hypothetical capital structures is to review the range of debt coverage ratios for the subject company assuming a certain level of debt. The appraiser then assigns the subject company a hypothetical bond rating (AAA, AA, A+, etc.) based on the typical ratios for companies with debt rated in each category assigned by one of the rating agencies.

Once a synthetic rating is determined, the appraiser can apply the average default spread for debt in the rating category. For instance, if companies with public debt rated in the AAA category have an average spread of 0.5% above the risk-free rate, that spread can be added to the current risk-free rate to estimate the current cost of debt for a AAA-rated company.

As debt is incrementally added to the capital structure, a company’s financial ratios will deteriorate, its synthetic debt ratings will worsen, and its estimated cost of debt will increase. The appraiser may need to subjectively add a small premium to each of the market-observed spreads, since the ratings are generally applied to large publicly traded companies. Obviously, a smaller privately held company will have a higher likelihood of default, and the incremental risk should influence the determination of the cost of debt.

Estimating the Cost of Equity at Each Level. The cost of equity must also be estimated at each point on the cost of capital curve. Application requires that the appraiser have an estimate of the company’s beta, as well as an estimate of the company’s debt/equity ratio.

This is straightforward when the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) was utilized to develop the subject company’s cost of equity at its existing capital structure. The appraiser simply has to calculate the unlevered beta (the beta as if the company had no debt) and then re-lever the beta at each level of debt. The re-levered betas are then used in the CAPM formula to estimate the company’s cost of equity at each level of assumed debt.

Estimating the WACC and Optimal Capital Structure. Once the company’s cost of debt and cost of equity are estimated at various capital structures, a weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is computed at each debt level. It is important to use a tax-affected cost of debt when computing the WACC in order to account for the tax benefits associated with debt.

The optimal capital structure for the firm is determined as that capital structure for which the company’s WACC is the lowest. The lower the company’s WACC, the higher the value of the firm, since the value of any company is the present value of the expected cash flows to the firm discounted at the WACC.

It should be apparent that an appraiser does not need to compute a WACC at every possible capital structure. Limiting the analysis to rounded increments (e.g. 10% debt, 20% debt, etc.) should provide a reasonable indication of an optimal capital structure.

Feasibility Testing

Once an optimal capital structure is derived using the method described above or one of the methods described in Part I of this article, the appraiser should perform an analysis to ensure that this capital structure is feasible for the subject company. This analysis simply entails calculating debt service payments on the prescribed level of debt to verify that the subject company generates enough cash flow to cover the debt payments and provide equity investors with a reasonable rate of return.

Because the optimal capital structure is hypothetically assumed to always be in place, one could assume that the business would need to generate only enough cash flows to cover interest payments. However, we believe that it is more prudent to encompass the payment of principal as well, since “real world” lenders require the repayment of principal, and continually rolling over the debt may not always be an option. Therefore, reasonable terms for debt repayment should be assumed, and an amortization schedule should be generated for the analysis.

If the feasibility analysis reveals that the cash flows of the subject company could not support the optimal capital structure indicated, the appraiser should incrementally reduce the level of debt in the analysis until the coverage ratios and rates of return to equity investors are reasonable.

Assumptions

In conclusion, we believe that a hypothetical (optimal) capital structure should be utilized when valuing a controlling interest under the fair market value standard, with the overriding assumptions being that (a) the ownership interest being valued would have the power to implement the capital structure; (b) the implied level of debt is attainable to the company at the estimated cost of debt; and (c) the cash flows of the business would be able to support this capital structure.

Like business valuation in general, estimating an optimal capital structure is not an exact science and requires the appraiser to rely on certain assumptions and exercise judgment that comes with experience. However, with a variety of methodologies at his or her disposal, the appraiser should be able to determine a reasonable and supportable optimal capital structure. ■