What have we learned from the worst downturn since the Great Depression

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

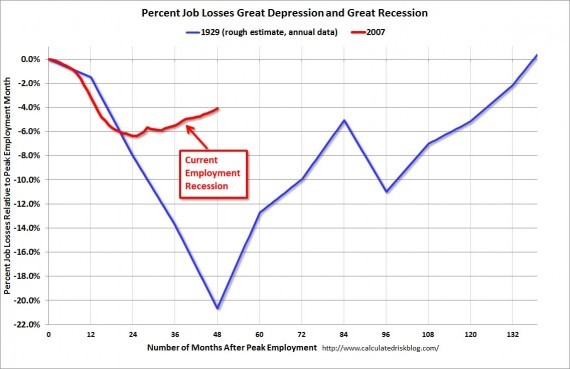

D enial. Complacency. Disbelief. Action. Those were the words that summed up the four phases of the deepest and most protracted recession to befall the British economy since the Great Depression of the 1930s. It was a downturn few saw coming, few thought would cause serious damage and few thought would last for very long. The experts – in the City, in government and academia – were wrong on every count.

Let’s turn the clock back almost two years to the early part of 2008 and six months after the realisation that the world’s banks were awash with toxic waste led to the seizing up of the financial markets. Alistair Darling was trying vainly to find a buyer for Northern Rock. while rumours were starting to swirl round Wall Street about the health of the investment bank Bear Stearns.

Before he became prime minister, Gordon Brown always liked to boast of how many quarters of growth Britain had enjoyed since the last recession in the early 1990s, and by the first three months of 2008 the number stood at 63. Analysts shared Brown’s view that the UK economy was fundamentally sound and was well placed to withstand the fallout from the US sub-prime crisis, pencilling in growth of 2% for 2009. In reality, the 63rd quarter of growth was to be the last; 2009 will see gross domestic product shrink by around 4.75% – the biggest fall in output of any year since 1921.

Denial gave way to complacency as the recession got off to a slow start. Unemployment started to rise slightly and the housing market softened but there was no sudden contraction in the economy. The flash estimate of GDP for the second quarter of 2008 was that output was flat; only later did the Office for National Statistics revise the figure down to –0.1%.

David Blanchflower, one of the members of the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee, spent the spring and summer warning there was something horrible out there, but was ignored. With oil prices rising steadily towards a peak of $147 a barrel in early July 2008, Threadneedle Street was more concerned about the prospect of inflation, which failed to materialise, than about a recession that was already happening. In August, a month before the collapse of the investment bank Lehman Brothers provided the catalyst for the most severe phase of the crisis, the Bank’s quarterly inflation report said the central projection was for output to be broadly flat over the next year or so, after which growth gradually recovers.

Between April and August, therefore, the Bank did nothing to help soften the imminent blow to the economy, even though doubts about the viability of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the companies that provide much of the mortgage finance for the US home loan market, were evidence of widespread financial distress. Interest rates were pegged at 5% between April and October, only being cut when the failure of the Bush administration to find a buyer for Lehman Brothers led to fears of global financial mayhem.

September 15 2008 was when complacency turned into disbelief at the scale of the threat. The first two dominoes to fall in the UK were symbolic of the shaky foundations on which the boom of the pre-crash years had been built: the Halifax was Britain’s biggest mortgage lender; the Royal Bank of Scotland had bought the Dutch bank ABN Amro for 50bn in the biggest ever financial deal.

Mayhem is a much over-used word in financial reporting, but is appropriate to describe what happened over the next four weeks. Share prices crashed and credit became almost impossible to obtain. There were fears not just about the viability of the world’s biggest banks but about countries as well. The Irish government was forced to give a blanket guarantee to depositors in its banks; Iceland was bankrupt in all but name. By early October 2008, two things were clear to policymakers: firstly, this was no longer a soft landing or even a common or garden recession but a potential re-run of the 1930s; secondly, they had to do something about it.

Action came in several forms. Nationalisation ceased to be a dirty word, with taxpayers’ money used to prop up the banks. John Maynard Keynes was rehabilitated as the Treasury cut taxes and raised public spending to blunt the impact of the downturn. Interest rates were cut swiftly and deeply to 0.5%, lower than at any time since the Bank was founded in 1694. There were specific measures to help the jobless, to prevent families from having their homes repossessed and to ease the tax burden on struggling companies.

The winter saw the worst of the retrenchment. Britain’s economy contracted by 1.8% in the third quarter of 2008 and by a record 2.5% in the first three months of 2009. Woolworths went bust, Honda shut its Swindon plant, the unemployment claimant count rose by 137,000 in a single month. Gradually, though, the burst of government activism started to have an effect. From the spring, the pace of decline started to moderate. House prices started to rise. Repossessions, business failures and job losses were all smaller than in the recession of the early 1990s, when the drop in GDP was not nearly so great. So rapid was the turnaround that the City was shocked when a sixth successive quarter of decline was reported in the third quarter of 2009.

The postmortem examination on the recession will continue long after today’s expected announcement of a return to growth. Some conclusions are obvious. It was bad, but not as bad as it might have been. It exposed the structural flaws in the economy – the over-reliance on debt-fuelled consumption and on the strength of the City of London. It leaves Britain with a legacy of public debt that will take years to pay down.

What is not yet clear is what happens next. After denial, complacency, disbelief and action comes a fifth phase. On past form, this will be recovery, relapse, rehabilitation or reform. It is unlikely to be amnesia.