What Short Interest and Institutional Ownership Tell You

Post on: 13 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

When I go to look up company facts, I find myself a bit bewildered by short interest and institutional ownership. I know these numbers are of great value but they’re difficult to understand. How I can use these statistics to better complete a given company’s analysis?

— Doug Bailey

Doug,

Short interest and institutional ownership can tell you the type of investors who own a stock.

Someone who shorts a stock is often negative about that stock’s prospects and is making a bet that it’s going to fall. Institutional ownership reveals how much stock is owned by fund companies, pension funds or other big organizations.

By themselves, these statistics cannot tell you whether a company is healthy or weak, or if the stock is a gem or a dog. However, they can certainly give you some insight into the market’s overall sentiment toward a stock or a sector.

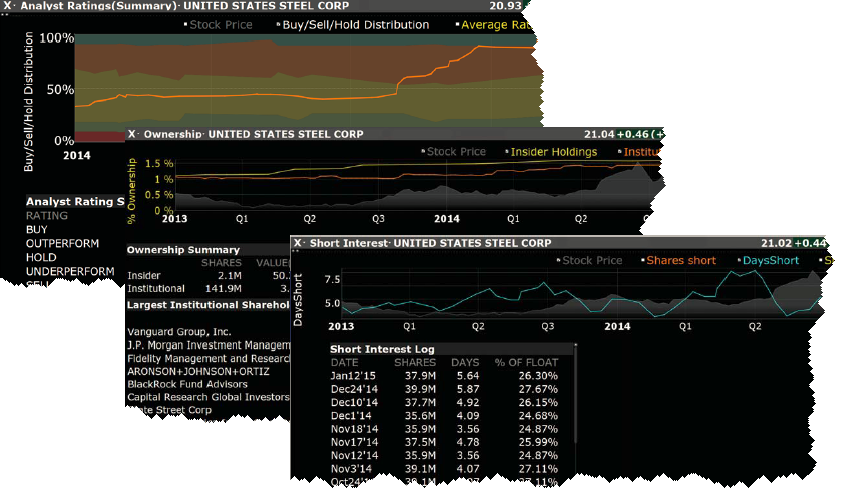

Short Interest

In a short sale, an investor borrows securities from a broker and sells them into the market with the understanding that the shares will have to be bought back and returned to the broker at a later date. If the stock falls, the investor buys back the stock at a cheaper price, making money on the trade. If the stock rises, the investor must fork over more cash to buy it back, thereby losing money.

The short interest in a stock, a widely available statistic, represents the total number of shares that have been sold short and not yet repurchased. This raw number won’t tell you much on its own.

Instead, you need to look at short interest as a percentage of the stock’s float, or the number of shares that are actively tradable in the market. This statistic will let you compare one stock’s short interest with that of others.

Many investors will short a stock because they think it’s going to fall. However, other investors might be short the stock for different reasons. You have no way of knowing from the statistics who is shorting, for what reasons. You may have better luck reading tea leaves than accurately interpreting these short-interest numbers.

If the majority of a stock’s tradable shares are being sold short, you can infer that a good number of investors are negative on that name. One fund manager offers this rule of thumb: Be concerned if more than 10% of a stock’s float is short.

In some instances, the message is obvious. Look at Globalstar Telecommunications (GSTRF ). the struggling satellite communications company that’s been experiencing weak subscriber growth among other problems.

A large chunk of this company’s shares is held short. Almost 62% of the stock’s float was short as of the middle of July, a high number by anyone’s measure.

But in this case, as in many others, the high short interest statistic doesn’t tell you anything you don’t already know from a look at the company’s fundamentals. It’s more a reflection of well-documented troubles.

Deciphering the short interest in other stocks can be difficult and fraught with risk.

I think it’s very difficult to make a judgment call on what short interest means, says Bernard Picchi, director of U.S. equity research at Federated Investors and the former head of U.S. stock research at Lehman Brothers.

Oftentimes, no real value judgment can be made, particularly if you see a very large short position for

big companies like

Why? Not everybody shorts a stock because he thinks it’s headed for the dirt.

For one, investors who are long the stock, or think it’s going to go up, might be short some shares to hedge their bets in case the stock does fall. The short offsets part of the long position and reduces the total exposure to the stock.

Brokerage firms will frequently short stocks when they don’t have the merchandise to sell to their customers. They will borrow the stock and pass it on to the customer, but ultimately have to close the short by repurchasing the shares in the market.

Other investors might short a stock as part of an arbitrage play in an attempt to profit by exploiting the price differences of identical or similar financial instruments.

To arbitrage two companies that are merging, you go long the company that’s being acquired, expecting its stock to rise, and short the company that does the buying, expecting its shares to fall.

This trade isn’t based on the thinking that something is fundamentally wrong with a stock or a company. It’s short-term speculation.

Too, some investors might short an otherwise strong stock because they think it’s overvalued and poised for a short downturn.

By glancing at the short-interest number, you cannot easily tell why investors are short. However, rising short interest is often interpreted as a near-term contrarian indicator, or a sign the stock could actually rise. Anyone with a short position must buy back those shares at some point in the future. If a lot of people are forced to buy the stock at a given time, its price will surely rise, which can happen during what’s called a short squeeze.

A squeeze occurs when a stock that has been shorted by many investors rises. More and more short-sellers start buying shares to cover their positions, driving up the stock price.

If you’re interested in buying a stock and discover that it has a large short interest, you may want to investigate it further to find out why people seem to be so negative. You might be hearing great things about that stock from a broker, but obviously some people don’t like it.

On the other hand, a stock’s short interest might not reflect any of the negative sentiment surrounding a stock. For example, you can’t short a stock if you can’t borrow the shares. But there are other ways to make money on falling prices like buying put options.

Institutional Ownership

Many mutual-fund managers and other large investors who wield billions of dollars like to see a high percentage of institutional ownership.

To these investors, a large number of institutional owners means the shareholder base is strong and investors are in the stock for the long haul. Of course, maybe these managers just want to feel secure in knowing that other big investors agree with their thinking.

More importantly, you may want to look at which institutions own a particular name.

Some investors want to see a firm like Fidelity and Janus in a stock. For one, these firms have dozens of analysts who are doing immense amounts of research on a company. Too, these money managers have been incredibly successful in the past, so their presence might tell you something.

Conversely, Federated’s Picchi says he stays away from names that are heavily owned by well-known momentum investors. (Think Pilgrim Baxter and Van Wagoner.)

At the slightest sign of trouble, they’re going to dump their shares.

Even if you’re a buy-and-hold believer in a stock, this quick-trigger selling could create volatility that you should be prepared for.

Ultimately, heavy institutional ownership won’t tell you definitively if a stock’s a solid investment or a shaky one.

Remember Cendant (CD ). This stock was a darling of many big money managers, and it fell flat on its face a couple of years ago.

Professional investors make mistakes, too.