View issue 15 Navigating the risks and opportunities in emerging markets

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

By Harry Broadman

Harry Broadman is Chief Economist and Leader of PwC’s Emerging Markets practice.

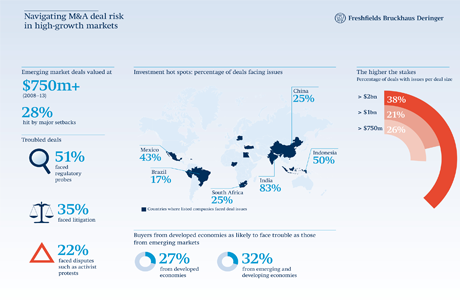

One question increasingly on the mind of a lot of corporate senior executives today is: What are the risk/opportunity tradeoffs of investing in emerging markets? Of course, emerging markets—a term that typically refers to all developing countries—are not a monolith. They are a very heterogeneous group. But the fact is that, as a whole, the rate of growth in emerging markets for the past decade and a half has been twice that of advanced countries, and this trend is unlikely to abate anytime soon. This is why there is increasing interest in emerging markets by companies in advanced economies, where growth has been much slower. Importantly, these growth differentials reflect a secular transformation in the structure of the global economy, not a cyclical phenomenon occasioned by the current economic/financial crisis. This is a critical distinction that too few corporate executives appreciate.

Understanding the challenges and rewards

There are, however, significant misperceptions about the challenges and rewards of doing business in emerging markets. In many cases, the risks are either highly understated or grossly overstated. The same is true with opportunities. Take China, for example. Many executives of large companies believe they should—and can—do business there. 1 From my experience having worked for two decades in China, the investment environment there is far more nuanced and complex than most investors appreciate. In my view, it’s a classic case of a place where the on-the-ground investment risks generally are understated. At the other extreme, consider Africa. Most corporate managers whom I talk to in developed countries lack accurate information about market conditions on the African continent. They don’t know that about one-half of the population in sub-Saharan Africa lives in countries where GDP growth, adjusted for inflation, has averaged more than 5 percent per year over the last two decades, or they don’t know that there is a burgeoning African middle class (and I’m not referring to South Africa alone, by any means). Indeed, a large number believe there simply aren’t any realistic investment opportunities in Africa. At the same time, people see African markets as fraught with excessive risk. There are, of course, appreciable risks of investing in Africa—just as there are substantial risks of investing in Latin America, Asia, the Middle East, the former Soviet Union, and so on. But the perceived risks in Africa are grossly overstated. In fact, according to recent data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Africa offers the highest risk-adjusted returns on foreign investment among all emerging economies.

It’s not just advanced country CEOs who are pondering investment in emerging markets. Powerhouse multinationals out of Brazil, China, India, and South Africa—among others—are themselves competing across their own geographies. At the same time, such firms are becoming bona fide contenders for market share in developed markets (North). Indeed, not only are the traditional trade and investment flows continuing between developed and developing economies, but there is tremendous growth in commerce among emerging markets (South-South). South-South trade now accounts for a sizable 20 percent of all global trade, and one-third of foreign direct investment outward flows originating from the South go to the South.

Implications for strategy and operations

What does this transformation mean for business strategy and operations of advanced country multinationals? They’re confronting a host of new risks and opportunities as they aim to compete not only with their longtime rivals from developed countries but also with world-class emerging market firms. Consider the athletic footwear industry. Most of the major athletic footwear firms are headquartered in the North but produce a majority of their output in the South, especially in China. And, as it happens, a sizable portion of Chinese production in this sector is exported to Brazil. The result is that Brazilian athletic footwear manufacturers feel they cannot effectively compete against the Chinese—so much so that Brazil believes these products are being dumped at an artificially low cost into the Brazilian market. Consequently, Brazil’s government placed a duty on imported Chinese athletic footwear. This ensuing trade war among the governments of two large emerging markets has sideswiped the world’s major branded athletic footwear companies, cutting their sales revenues and leaving these companies with little recourse for remedies in the short run.

In light of all this, how do Northern multinationals move forward to exploit the new opportunities arising in the fast-growing emerging markets while mitigating the risks? The first critical step is to ensure you know your customers, your partners, the particular government with which you’re dealing, and other stakeholders. The best way to do this is to carry out tailored due diligence, employing different types of lenses and techniques and especially by using independent, verifiable sources.

To be sure, carrying out world-class due diligence can be more difficult in emerging markets since, by definition, their institutions are nascent and their information frameworks less developed. I frequently see companies rely on self-proclaimed experts in the local economies, only to discover that these people themselves are not the best people to have relied upon. The ability to perform world-class due diligence comes from having done it repeatedly throughout challenging parts of the world so there is the capacity to recognize similar problems when they crop up, and the information is collected and interpreted by parties who are independent to the transaction and are mutually trusted by all sides.

Such due diligence can be applied in a number of ways by foreign investors to effectively mitigate risks and maximize opportunities. One approach is to establish business-to-business (B2B) alliances. For example, a multinational electric power company might establish a B2B agreement with an oil company in Vietnam because that’s a high-risk, high-return market. If the B2B performs well, the two companies could replicate the relationship elsewhere in Southeast Asia or in another region.

Business-to-government agreements or public-private partnerships are another avenue. A multinational engineering and construction company recently signed a 15-year master service agreement with the government of Gabon to become an anchor investor and provide management and technical support to the government as it develops a national infrastructure master plan. Similarly, a major beverage multinational has formed a partnership with a large private foundation, three African governments, and a project management entity that provides for local fruit farmers to sell juice to the beverage’s supply chain, substituting for juice imports. Win-win solutions like these expand the bottom line and also fulfill legitimate objectives on the part of a government to spur growth and create jobs.

For more ways corporations can manage risk while exploiting opportunities, see the graphic below.

This list, of course, is not exhaustive. But it illustrates the type of tactics that, if adopted, can significantly reduce a firm’s exposure to risks.

Adapting to change

The industrial landscape of the world market has changed unalterably. But this is just the beginning. There will be multiple growth nodes from here on out and not just between the advanced countries and the emerging markets—but within emerging markets. The effect on companies from the developed world will continue to be profound. Adopting an investment strategy informed by accurate information and trusted partners with deep local insights and experience is the best way to navigate the risk-opportunity tightrope. But the biggest risk in emerging markets could be just ignoring them.

1 For a recent discussion on China, see “Pearls, pitfalls, and possibilities,” Marketmap. Issue 1, 2011.