The Fed s POMO Isn t Really Driving Stocks Higher

Post on: 6 Май, 2015 No Comment

Don’t fight the Fed has become the Fed won’t let stocks go down. Welcome to this market cycle’s new paradigm.

There’s an unquestioning, disquieting assurance pervading market channels thats shared by the sophisticated and simple alike: The Fed’s continued accommodative stance isn’t just an effort to be vaguely supportive of asset prices. It is pursuing fulfillment of a shadow mandate to actively guide US stocks higher.

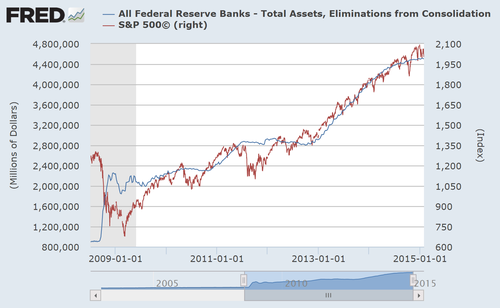

Apparently, the Fed is quite good at it, too, or so the following chart from YCharts would suggest. It plots the growth curve of the Fed’s balance sheet against the S&P 500 Index (INDEXSP:.INX).

20Chart.png /%

The relationship depicted in this chart is undeniable: Fed balance sheet growth (read: QE) has a high positive correlation to US equity market prices. Moreover, passages where the correlation does break down – mid-2010, mid-2011 – correspond to cessation (end of QE1 and QE2, respectively) in the Fed’s large-scale asset purchase (LSAP) efforts.

Recognition of this relationship is nothing new: It’s been a topic of constant and increasing conversation and debate since the data series began to show a perceptible correlation in early 2009. In fact, cognizance of the Fed’s presumed support of the US equity market is so widespread that the Zero Hedge-originating colloquialism BTFD has become a universally-acknowledged market meme.

Its not just dispassionate recognition, though. There is a capitulative sense of resignation among many (well-chastened) bears — not only in affirmation of the old don’t fight the Fed saw, but that stocks will not meaningfully decline while the Fed’s LSAP program continues at full steam.

Many (most?) market observers have signed on to this apparent inevitability, and as we’ve just seen, the data is superficially compelling. In short, stocks will go up while the Fed remains dovish, fait accompli .

Is the Fed Really Causing Stocks to Go Up?

There are two nagging problems here that not only refuse to go away, no matter how far out into the wilderness of slighted opinion they’re pushed.

- Is the Fed’s LSAP (QE) program causing equities to rise as a direct result of its stock and flow mechanisms via permanent open market operations (POMO), or are they only correlated ?

- How much of the rise in equity prices is attributable to positive market reflexivity rather than LSAP?

Fed antagonists like to argue (ardently) that the above chart represents a causal relationship. Their claim is a simple one: The Fed is pumping liquidity into the system via POMO, and most of those flows are ultimately directed into stocks by proxy of the Primary Dealers.

It’s a fascinating narrative, carrying a plausible nuance of conspiracy theory. Whose curiosity isn’t piqued by the story of a massive program of systemic byzantine intrigue whereby the Fed – in complicity with an elite, massively profitable banking cabal – relentlessly pushes stocks higher?

Those who overlay this cause narrative on the chart above appeal to the data to press its credibility.

The problem? The data thats appealed to doesn’t do the necessary explanatory work. Correlations are easy: recognize a relationship between two variables and the work is done. Causality is something else.

Recent market commentary is replete with examples that attempt to make the case. Take Zero Hedge’s coverage of the US Treasury’s recent admission that It’s All POMO. After the breathless reporting is done, the positive correlation between POMO and the S&P 500 is very well established; but however compelling the argument (never mind the Treasury really doesn’t admit anything), it does not add up to a causal link.

The common rejoinder? Maybe no one has empirically demonstrated this relationship with incontrovertible proof built from concrete data, but the chart strongly alludes to it, and that’s enough.

So the Fed Isn’t Directly Causing Stocks to Go Up. So What?

But, it’s not enough – not for what is really a very radical claim. No one has proven this claim, and no one has falsified it. The data to do one or the other exists, but much of it is proprietary or otherwise inaccessible. In the absence of that evidence, the burden of proof rests on those making this cause claim, and thus far they have failed to meet it.

Does it matter? Yes, because if the Fed isn’t causing this; it may not have the market’s back in the manner or to the degree that is widely assumed. If the presumption that the actual POMO mechanism is bidding stocks is not accurate, the assurance that this relationship exists has created a significant moral hazard, or as Ross Heart sharply observed recently, a bubble in certainty. Isn’t the Fed’s entire communications effort an attempt to remove the element of monetary policy surprise and the volatility it can create?

Maybe POMO Isn’t the Cause. but Then What Is?

Consider the eurozone’s debt crisis for a moment.

Early last year, EZ periphery sovereign bond yields were at crippling levels. Harsh fiscal austerity regimes were the norm, political ineptitude was all-pervasive, and an endless parade of block-wide acronym-riddled crisis-management progams (remember the EFSF and ESM?) populated international financial news headlines.

Then ECB President Mario Draghi used the phrase whatever it takes. By assuring markets of the ECB’s commitment to make the euro irreversible, Draghi leveraged the central bank’s strong credibility to stem (for the moment at least) the sweeping tide of pessimism over the future of the Euro area and currency.

What did the ECB do? Nothing but issue a verbal commitment to its mandate and an implicit dare to those who doubted it.

The introduction of the ECB’s Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) program epitomizes this. Draghi has celebrated the program’s potency as a fully effective backstop against EZ member insolvency. That the program does not exist is of secondary importance: The assurance that it could exist was enough to reinstate confidence and decisively break the hold euro-skepticism was beginning to assert with authority over bond markets. Nothing substantive needed to change in the eurozone to effect the great shift that followed in bond yields and equity prices. The ECB effectively sparked a positive belief, the market picked it up, and the positive cycle of reflexivity did the rest.

It’s true the Fed has done much more than issue verbal commitment (though it has done that with mixed success through its communication policy). The various crisis-mitigating and rehabilitative facilities and programs it has employed since the dark days of 2008 have added almost $3 trillion to its balance sheet, though much of it with negligible direct success .

Communication policy well-executed is not unlike propaganda. The Fed’s Open Market Committee (FOMC) dangles select and minimally sufficient information about its sentiment, forecasts, and projectes rate path into the expectations channel by various media (e.g. speeches, statements, Q&A, papers) to manage the perception of its observers. Increasing acknowledgement of the apparent success of this more transparent approach to market suasion coincides with the current forward guidance policy fad that has swept global monetary policymakers.

Where’s there’s credibility, communication will inspire confidence. As the ECB has almost effortlessly demonstrated, that (and a token tip of the hat to hard policy execution) is often enough to induce markets to march in the desired direction.

All You Need Is Love (or Confidence)

With that in mind, revisit the second question above: How much of the rise in equity prices is attributable to positive market reflexivity rather than LSAP?

The virtuous feedback loops markets are capable of, where confidence is instilled and fostered, can have immense consequences.

In the current market environment, where the concrete efficacy of the LSAP mechanism ends, the BTFD-POMO meme-propelled positive feedback loop takes over to do the heavy lifting. In the parlance of Fed economists. the rate-suppressing impact of the stock effect – and all its supposed second-round effects – does its work; but its the implicit form of policy communication realized through the ongoing flow effect (i.e. POMO) that is responsible for keeping the loop spinning.

I’m not suggesting QE flows aren’t going into equities. Undoubtedly some are.

The proportion, though, is probably minimal. Others have noted this (take Mark Dow’s brief but persuasive rebuttal. for instance), but the position is not popular.

But what does that matter when a market closely fixated on the POMO schedule sees that the Fed is juicing the Primary Dealers to the tune of, for example, $4 billion of Treasuries and/or MBS on a given day? If the shared supposition held by the market is that this day-in, day-out activity is a constant reaffirmation of the Fed’s got my back, speculative yield-chasing, return-chasing capital will flow into stocks. One need look no further than the tight price reflexivity engendered by the constant injections listed in the above schedule to explain the quality of the balance sheet/SPX correlation.

Take a look around: A brief search through social media reveals this supposition is very widely held. The cloak-and-dagger, conspiratorial aspects of it may not be, but recognition of the feedback loop (POMO), its presumed cause (the Fed, Primary Dealers) and its apparent results (S&P 500 +160% since March 2009) can be found everywhere. Some genuinely adhere to the cause thesis, while other, more opportunistic parties simply recognize a trend to exploit.

POMO Money, POMO Problems

However it gets there and wherever it comes from, flows are chasing the POMO meme. In this way, one could plausibly argue that POMO is causing the S&P 500 to rise; but it isn’t (or isn’t just) the mechanism itself – it is the meme inspired by the underlying program held in the mind of the market program that does the least of the work.

How much confidence the Fed has inspired through POMO and what proportion of the S&P 500′s cumulative 5-year performance is predicated on it is impossible to say. But the beneficial reciprocity shared by market prices and the confidence the Fed has engendered do point to at least a shared cause relationship with the actual POMO mechanism – one where nothing more than the momentum of shared belief may be driving stocks up.

If that is the case – and it is, otherwise non-Fed market sentiment, whether optimistic or pessimistic, has been rendered entirely meaningless – the gap/air pocket/bubble between what the Fed is actually doing/will do and what market participants believe it is doing/will do is a major discrepancy.

A discrepancy of moral hazard ironically created by the Fed’s failure to effectively and prudently communicate in this era of peerless transparency.

This article by Andrew Kassen was originally published on See It Market .