THE EFFICIENT MARKET HYPOTHESIS ON TRIAL

Post on: 22 Июль, 2015 No Comment

1. Efficient Market Hypothesis

la. The Specifics

First, what do we mean by an Efficient Market Hypothesis? The simplest explanation would be that securities prices reflect information. Fama (1970) made a distinction between three forms of EMH: (a) the weak form, (b) the semi-strong form, and (c) the strong form. However, it is the semi-strong form of EMH that has formed the basis for most empirical research.

The strong form suggests that securities prices reflect all available information, even private information. Seyhun (1986, 1998) provides sufficient evidence that insiders profit from trading on information not already incorporated into prices. Hence the strong form does not hold in a world with an uneven playing field. The semi-strong form of EMH asserts that security prices reflect all publicly available information. There are no undervalued or overvalued securities and thus, trading rules are incapable of producing superior returns. When new information is released, it is fully incorporated into the price rather speedily. The availability of intraday data enabled tests which offer evidence of public information impacting stock prices within minutes (Patell and Wolfson, 1984, Gosnell, Keown and Pinkerton, 1996). The weak form of the hypothesis suggests that past prices or returns reflect future prices or returns. The inconsistent performance of technical analysts suggests this form holds. However, Fama (1991) expanded the concept of the weak form to include predicting future returns with the use of accounting or macroeconomic variables. As discussed below, the evidence of predictability of returns provides an argument against the weak form.

While the semi-strong form of EMH has formed the basis for most empirical research, recent research has expanded the tests of market efficiency to include the weak form of EMH. There continues to be disagreement on the degree of market efficiency. This is exacerbated by the joint hypothesis problem. Tests of market efficiency must be based on an asset-pricing model. If the evidence is against market efficiency, it may be because the market is inefficient, or it may be that the model is incorrect. The literature documented below presents evidence of inefficiencies based on existing models and more recent research findings that cast doubt on these models.

lb. The Initial Euphoria and Subsequent Discontentment

The EMH has provided the theoretical basis for much of the financial market research during the seventies and the eighties. In the past, most of the evidence seems to have been consistent with the EMH. [1] Prices were seen to follow a random walk model and the predictable variations in equity returns, if any, were found to be statistically insignificant. While most of the studies in the seventies focused on predicting prices from past prices, studies in the eighties also looked at the possibility of forecasting based on variables such as dividend yield (e.g. Fama & French [1988]), P/E ratios (e.g. Campbell and Shiller [1988]), and term structure variables (e.g. Harvey [1991]). Studies in the nineties looked at inadequacies of current asset pricing models.

The maintained hypothesis of EMH also stimulated a plethora of studies that looked, among other things, at the reaction of the stock market to the announcement of various events such as earnings (e.g. Ball & Brown [1968]), stock splits (e.g. Fama, Fisher, Jensen and Roll [1969]), capital expenditure (e.g. McConnell and Muscarella, [1985]), divestitures (e.g. Klein [1986]), and takeovers (e.g. Jensen and Ruback [1983]). The usefulness or relevance of the information was judged based on the market activity associated with a particular event. In general, the typical results from event studies showed that security prices seemed to adjust to new information within a day of the event announcement, an inference that is consistent with the EMH. [2] Even though there is considerable evidence regarding the existence of efficient markets, one has to bear in mind that there are no universally accepted definitions of crucial terms such as abnormal returns, economic value, and even the null hypothesis of market efficiency. To this list of caveats, one could add the limitations of econometric procedures on which the empirical tests are based.

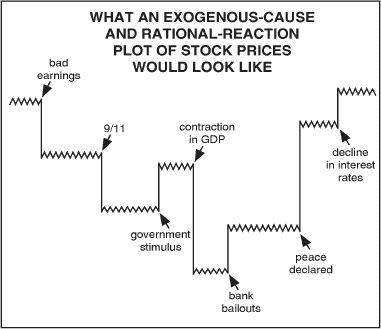

The early euphoric research of the seventies was followed by a more cautioned and critical approach to the EMH in the eighties and nineties. Researchers repeatedly challenged the studies based on EMH by raising critical questions such as: Can the movement in prices be fully attributed to the announcement of events? Do public announcements affect prices at all? and What could be some of the other factors affecting price movements. For example, Roll (1988) argues that most price movements for individual stocks cannot be traced to public announcements. In their analysis of the aggregate stock market, Cutler, Poterba and Summers (1989) reach similar conclusions. They report that there is little, if any, correlation between the greatest aggregate market movement and public release of important information. More recently, Haugen and Baker (1996) in their analysis of determinants of returns in five countries conclude that none of the factors related to sensitivities to macroeconomic variables seem to be important determinants of expected stock returns.

1c . The Current Debate

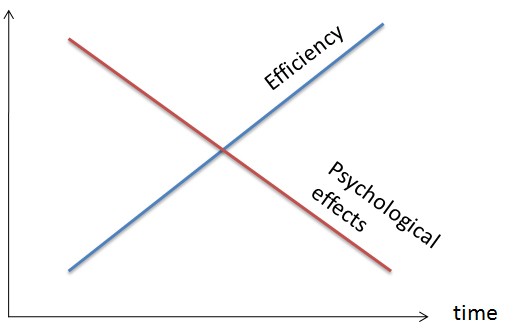

The accumulating evidence suggests that stock prices can be predicted with a fair degree of reliability. Two competing explanations have been offered for such behavior. Proponents of EMH (e.g. Fama and French [1995]) maintain that such predictability results from time-varying equilibrium expected returns generated by rational pricing in an efficient market that compensates for the level of risk undertaken. Critics of EMH (e.g. La Porta, Lakonishok, Shliefer, and Vishny [1997]) argue that the predictability of stock returns reflects the psychological factors, social movements, noise trading, and fashions or fads of irrational investors in a speculative market. The question about whether predictability of returns represents rational variations in expected returns or arises due to irrational speculative deviations from theoretical values has provided the impetus for fervent intellectual inquiries in the recent years. The remainder of this paper is motivated largely by this issue, and places greater emphasis on the speculative aspect.