The Cure for Low Oil Prices

Post on: 7 Июль, 2015 No Comment

The downward trajectory of oil prices since the beginning of November has caused consternation in many parts of the world—particularly those economies reliant on oil exports. A meeting of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) at the end of November failed to stem the fall. But as global oil prices head toward levels considered unsustainable, Colin Morton, vice president and portfolio manager, Franklin UK Equity Team, reckons the laws of supply and demand will take over.

Colin Morton, Vice President, Portfolio Manager

Franklin UK Equity Team

Colin Morton

We’ve been as surprised as anybody by the speed of the decline in the price of oil, but there’s a saying in the oil sector, attributed to various commentators over the years: “The cure for high oil prices is high oil prices.” And we think the corollary is also likely to be true: “The cure for low oil prices is low oil prices.”

Of course, we recognise that it is very difficult to come up with a definitive number for what the oil price should be. But we believe that over the medium term, it should likely pick up from its current level for a variety of factors.

The price per barrel of Brent crude oil had been above US$100 for a number of years and seemed relatively stable around that area, while West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil had also seen spikes above US$100. Indeed, both oil benchmarks traded between US$100 and US$115 this past summer. But in recent weeks prices have collapsed, with both global oil benchmarks falling below US$70 per barrel.

We believe there have been two reasons for that: The demand for oil is not as high as people thought it would be, and the supply has held up better than predicted.

On the demand side, we’ve seen reductions in forecast for demand, particularly in Europe, which economically has been performing poorly. The emerging world, notably China, also has not generally achieved the sustained growth that some observers had predicted.

Although the US economy has reported good growth figures this year, some disappointing economic data from parts of Europe, China and Japan (officially declared to be in recession in November 2014 after two quarters of contracting GDP) have prompted central banks to take action to stimulate their respective economies. Eurozone GDP growth was a mere 0.2% in the third quarter of 2014, 1 and China’s third-quarter GDP growth was 7.3%, the lowest annual growth rate since the first quarter of 2009. 2 The divergence in growth expectations between the United States and the rest of the world is also reflected in currency markets, as you can see in the chart below from the US Energy Information Administration.

Meanwhile, despite tensions in the Middle East, as well as in Russia and Ukraine, supply has held up very well. Some observers were expecting supply disruptions because of those conflicts, but so far we’ve not really seen significant supply issues.

At the same time, we have the added contribution to global oil supplies from the production of shale oil, particularly from the United States.

The Investment Implications of Lower Oil

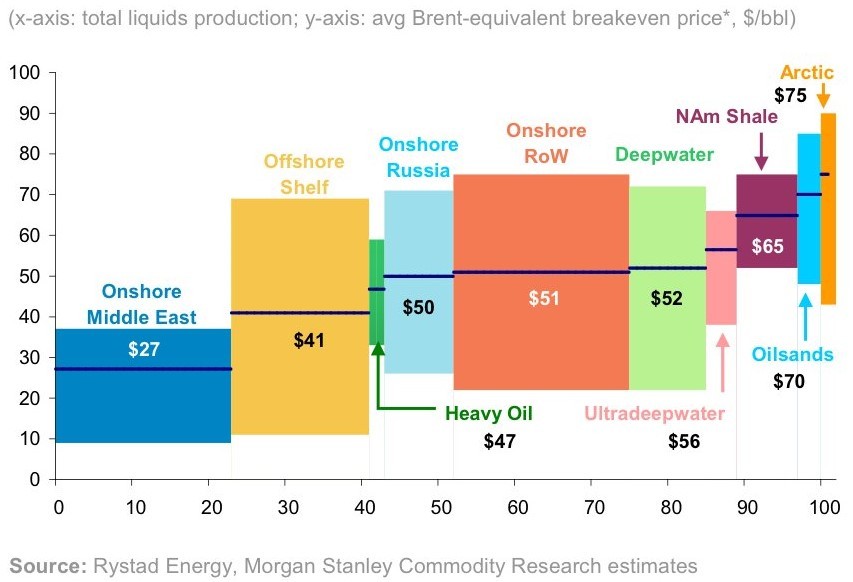

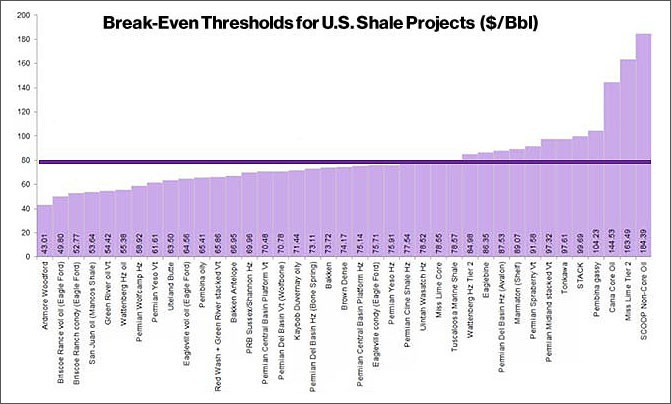

Our analysis now centres on an estimation of the break-even price of oil and, in particular, how much it costs to get a barrel of oil out of the ground, because that will likely have significant implications on investment in the sector in the future.

For example, our research suggests US shale oil tends to start to look a bit more worrying from a margin perspective at around US$65 to US$70 a barrel. A lot of these shale projects in the United States are quite short-term projects. Once you’ve decided to extract oil, the process might last only a year or so, and then you have to move somewhere else. So in our view, oil prices around that US$65 to US$70 break-even level or lower will make investment decisions more difficult in the future.

We’re also considering where the new production of oil is coming from over the next five to 10 years. We think that in order for the investments required to make future production commitments viable, the price of oil will likely need to be significantly above US$70 per barrel. US$90 per barrel seems closer to the number a lot of companies are using in their forecasts.

Amid lower prices, we believe upstream companies are likely to be much more careful about investment decisions going forward and that, in turn, could result in a reduction of production going forward.

But what we also don’t think people are taking into consideration enough is the likely increase in demand, which stems from lower prices.

Certainly, we realise a low oil price is good for the consumer in the short term; consumers should be able to see the effect at the fuel stations and reflected in their energy bills and transportation costs.

However, there’s a danger that if oil prices stay low for longer, the energy firms may have to take more drastic action on costs, including cutting back spend on exploration and research and development, which in turn could mean that if and when prices do rise again, they may go to a price higher than they would otherwise have been, which would likely be bad news for the consumer longer term.

We remain long-term investors, but at the moment we’re not letting the current low level of oil prices have a huge influence on our investing decisions. We are not using this situation as an opportunity to buy loads of consumer stocks as we’re not convinced the price of oil is likely to stay low for the long term, but equally, we’re not prepared to put a lot of money into oil stocks at the moment either, because we don’t know how long the current situation will last.

In summary, we remain very much of the view that oil prices should be higher than they are now, but we really don’t have a solid short-term idea of where prices will be in the next six to 12 months. Over the medium term, we think oil should see a recovery price back above the cost of extracting it.

The comments, opinions and analyses are the personal views expressed by the investment manager and are intended to be for informational purposes and general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice. The information provided in this material is rendered as at publication date and may change without notice and it is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region, market or investment.

Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton Investments (“FTI”) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. FTI accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information and reliance upon the comments, opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user. Products, services and information may not be available in all jurisdictions and are offered by FTI affiliates and/or their distributors as local laws and regulations permit. Please consult your own professional adviser for further information on availability of products and services in your jurisdiction.

What Are the Risks?

All investments involve risk, including possible loss of principal. The value of investments can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Stock prices fluctuate, sometimes rapidly and dramatically, due to factors affecting individual companies, particular industries or sectors, or general market conditions. Special risks are associated with foreign investing, including currency fluctuations, economic instability and political developments. Investments in the natural resources sector involve special risks, including increased susceptibility to adverse economic and regulatory developments affecting the sector.

Get more perspectives from Franklin Templeton Investments delivered to your inbox. Subscribe to the Beyond Bulls & Bears blog.

For timely investing tidbits, follow us on Twitter @FTI_Global and on LinkedIn .

1. Source: Eurostat, 14 November 2014.