Tax Report The Great DividendTax Mystery

Post on: 3 Май, 2015 No Comment

Laura Saunders

Updated April 24, 2010 12:01 a.m. ET

Next year, what will the top tax rate on dividends be?

Investors like Clint Myers, an investment actuary in Georgetown, S.C. want to know. Some experts cite a 20% figure, while others say 39.6%, and still others talk about a tripling of the current 15% rate. Lately I have seen figures citing almost any rate you can imagine, Mr. Myers says.

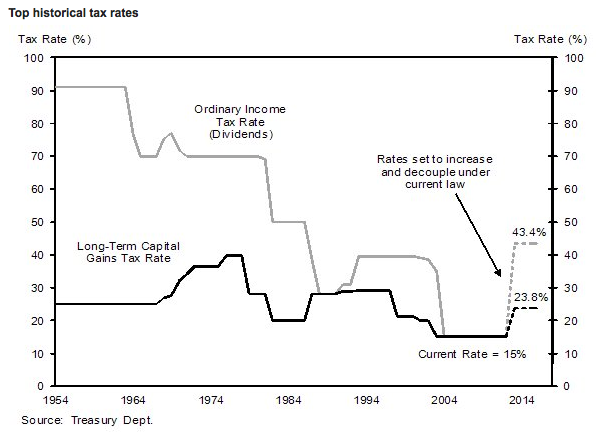

Next Jan. 1, a package of tax changes enacted under President George W. Bush expires. These provisions contained a historic change for dividends: For the first time, most were taxed at the same low rate as capital gains. Until then dividends had been grouped with interest, with both taxed at the higher rates levied on wages. In 2003 the nominal top rate on qualified dividends (usually, on stocks held longer than two months) dropped to 15%, where it has been ever since.

ENLARGE

Mark Matcho

If Congress doesn’t act, this reclassification will lapse at the end of 2010, and next year the top dividend rate would automatically revert to 39.6%.

But this lapse isn’t likely to happen, for a reason many have overlooked. Lawmakers can’t simply allow the Bush changes to expire in the way they did with the estate tax, because the lapse would affect even more low earners than high earners. When taxes were cut for those in top brackets, they were also cut for those at the bottom. According to the Tax Policy Center, letting the Bush changes expire would push six million lower-income households back on the tax rolls. The way the law is written, Congress can’t let some changes expire while retaining others unless it acts.

So Congress seems likely to do something. But what?

The Republicans favor extending the Bush tax changes outright, and Democratic lawmakers and the president himself have expressed a desire for lower dividend taxes. A provision in the Obama budget calls for leaving dividends in the same lower-rate category as capital gains. If this holds, the top rate on dividends could rise to 20% next year, the rate President Obama favors on long-term gains. That would be higher than the rate now, but barely half what some expect.

The big question is how to pay for it. Under complex pay as you go budget rules, says Clint Stretch of Deloitte Tax, lawmakers have to find money for a 20% rate. That is because even though this rate would be higher than the current one, it is considered a tax cut from the expected 39.6% rate.

You read that correctly: It is both a tax rise and a tax reduction. In an election year, there just isn’t any telling what legislators might do with a political football like that.

More in the Weekend Investor

Yet another issue affecting the outcome is that this year lawmakers already enacted a 3.8% tax on investment income for top earners to help fund health care. It takes effect in three years, and if lawmakers opt to resume taxing dividends like interest—presumably at a 39.6% rate—that would push the top nominal rate on dividends above 43% in 2013. The specter of this high rate is likely to provoke a firestorm in an election year. In the heat of legislation almost anything can happen, even a compromise that keeps the 15% rate a while longer. Mr. Stretch expects the issue to surface in Congress before the August recess.

No wonder Mr. Myers and others are dizzy with confusion. The upshot is that next year the after-tax value of a 4% dividend yield on $100,000 of stock could be anything from $3,400 to less than $2,500 (before state taxes), and higher tax rates could lower the value of the underlying holding. Hardest hit, says Robert Gordon of Twenty-First Securities, could be utility stocks and fixed-rate preferreds with no way to adjust upward. He suggests a portfolio review to check for vulnerable spots.

The outcome affects more than investors’ pocketbooks, though. The taxation of dividends also touches a crucial policy issue. For decades some economists have criticized the lopsidedness at the core of the U.S. tax system, which taxes the returns on debt once but the returns on equity twice. Payments of interest are deductible to a firm, whereas dividends aren’t; both are taxable to the holder.

This may sound arcane, but the distortions can be real. Some experts worry that the imbalance gives corporate executives an excuse to load up on debt or skimp on dividends in the name of sound capital allocation. During 1986’s major tax overhaul, an early version gave corporations a deduction for dividends, recalls former Treasury official Ronald Pearlman, an architect of the overhaul. But it disappeared. Large firms weren’t that interested or supportive of it, he says.

Still, notes Howard Silverblatt of Standard & Poor’s, over the past two decades dividends have accounted for more than 40% of the total return on the S&P 500-stock index, and they nearly erased this decade’s 18% loss. Since the law was changed in 2003, the tax cut on dividends has put more than $390 billion into investors’ pockets. The higher the tax rate on dividends, he says, the less incentive there will be for corporations to pay them.