Tax Loss Harvesting

Post on: 17 Август, 2015 No Comment

Your e-mail has been sent.

It’s on many year-end to-do lists—“harvest” your investment gains or losses. In plain English, that means selling stocks, bonds, and mutual funds that have lost value to help reduce taxes on capital gains realized from winning investments. Tax-loss harvesting can be an important strategy, especially for high-income investors, because of last year’s three tax increases:

- The highest tax rate on long-term capital gains increased to 20%, from 15%;

- A new 3.8% Medicare surtax for high-income taxpayers pushed the highest effective long-term capital gains tax to 23.8%; and

- The top tax bracket is 39.6% for ordinary income, nonqualified dividends, and short-term capital gains. The previous top rate was 35%. With the Medicare surtax, the effective rate can now be as high as 43.4%.

Even if you aren’t hit by higher rates, tax-loss harvesting can still be an effective tax strategy, potentially helping to reduce the costs of rebalancing. Rebalancing is a key to ensuring your investment mix (i.e. stocks, bonds, and short-term investments) is aligned to your investment time frame, financial needs, and comfort with volatility.

How much can you save?

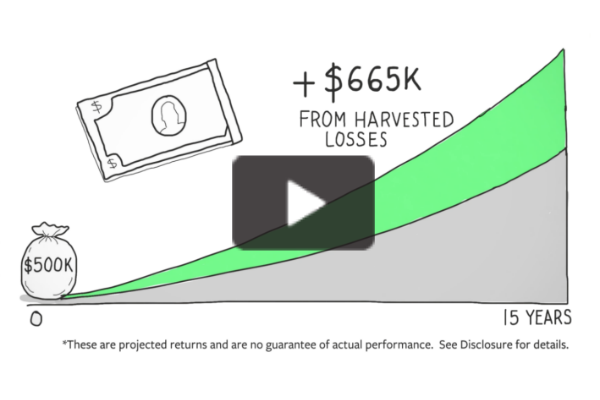

The size of the potential benefit from tax-loss harvesting depends on two key factors: your income level and the amount of short- and long-term capital gains, minus any current losses that you may have already realized or any losses carried forward from other years.

Short-term capital gains are those realized from investments that you have owned for one year or less, and they’re taxed at the marginal rate you pay on ordinary income. The top marginal tax rate on ordinary income is 39.6%. For 2014, it applies to couples filing jointly with income above $457,600, and single taxpayers with income above $406,750. For those subject to the Medicare surtax, the effective rate can be as high as 43.4%. And with state and local income taxes added in, the rates can become even higher.

Long-term capital gains. those realized from investments held for more than a year, are taxed at significantly lower rates. You won’t owe any long-term capital gains tax if your 2014 taxable income is below $73,800 and you are married filing jointly, or $36,900 if you are a single filer. For the majority of taxpayers—those with taxable income between $73,801 and $457,600 (married, joint filers) and $36,901 and $406,750 (single filers)—the long-term capital gains rate is 15%.

High-income taxpayers, on the other hand, are subject to higher rates. If your taxable income is more than $457,600 (married joint filers), or $406,750 (single filers), your marginal rate for long-term capital gains is at least 20%.

However, the 3.8% Medicare surtax means that the actual long-term capital gains tax rate for high earners can be as much as 23.8%, and the actual rate applied to other investment income can be as high as 43.4%. The surtax is levied on the lesser of (1) net investment income or (2) the amount by which modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) exceeds $250,000 for couples filing jointly, and $200,000 for single filers.

For example, a couple with MAGI of $270,000, of which $50,000 was net investment income, would owe the 3.8% surtax on $20,000 (the amount by which their MAGI exceeded the $250,000 threshold, which is less than the $50,000 in net investment income). If the couple had $330,000 in MAGI, of which $50,000 was net investment income, they would pay the surtax on $50,000 (the amount of their net investment income, which is less than the $80,000 excess of their MAGI over the $250,000 threshold).

Prioritizing your tax savings

2014 vs. 2013 tax rates

To help maximize your tax savings, you should apply as much of your capital loss as possible to short-term gains, because they are taxed at a higher marginal rate. This is particularly true for high-income investors.

For example, if you’re in the top tax bracket, the difference between short- and long-term gains can be as high as 19.6% (43.4% versus 23.8%). However, if you’re in the 25% tax bracket—$73,801 to $148,850 for joint filers and $36,901 to $89,350 for singles—the difference between the short- and long-term gains rate is 10% (25% versus 15%).

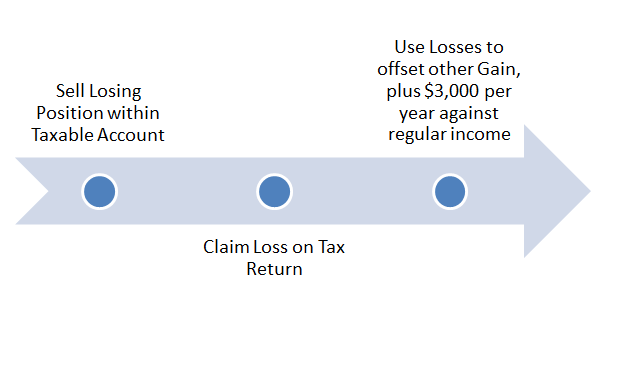

According to the tax code, short- and long-term losses must be used first to offset gains of the same type. But if your losses of one type exceed your gains of the same type, then you can apply the excess to the other type. For example, if you were to sell a long-term investment at a $15,000 loss but had only $5,000 in long-term gains for the year, you could apply the $10,000 excess to any short-term gains.

Realizing a capital loss can be effective even if you didn’t have realized capital gains of either type this year. The tax code allows you to apply up to $3,000 a year in capital losses to reduce ordinary income, which is taxed at the same rate as short-term capital gains and nonqualified dividends. If you still have capital losses after applying them first to capital gains and then to ordinary income, you can carry them forward for use in future years.

The least effective implementation of a tax-loss harvesting strategy, on the other hand, would be to apply short-term capital losses to long-term capital gains. But, depending on the circumstances, that may still be preferred over paying the long-term capital gains tax.

Keep in mind

Don’t let lowering your current-year taxes undermine a diversified investment portfolio. A tax-loss harvesting strategy should always fit with your overall investment strategy. Good candidates for tax-loss harvesting are depreciated investments that no longer fit your strategy, that have poor prospects for future growth, or that can be replaced by other investments that are similar (but not exact matches) to the ones you are considering selling.

It is possible to sell a depreciated investment that you still want in your portfolio by investing the proceeds from the sale in another asset that is not “substantially identical” (as defined by the IRS), then selling it and buying back the original investment more than 30 days after the sale date. If you repurchase the investment too soon or invest in something the IRS deems substantially identical to the original security, such as a call option on it, the IRS “wash sale” rule will generally disallow the loss deduction. There’s also a risk that the substitute investment you buy will increase in value during the 30-day waiting period, and you’ll realize a short-term gain if you sell it. On the other hand, if the substitute does not rise in price over the 31-plus-day period, but the original asset does, you may miss out on some of the gain.

If you want to maintain exposure to the industry of the stock held at a loss, you might consider using an exchange-traded fund (ETF) as a substitute following a tax-loss harvest sale. Read Viewpoints. “Tax-loss harvesting using ETFs .”

What to do now—and next year

If you plan to implement a tax-loss harvesting strategy to offset a portion of your gains, be sure to research your records carefully on any asset you are considering selling. You’ll want to be certain about the cost basis (the price you paid to purchase a security plus any additional costs such as broker’s fees or commissions) of your depreciated investments—which determines the extent of your loss—before you make your move. To check the amount of capital gains and losses in your nonretirement Fidelity accounts—and determine whether they’re short or long term—use our tax loss harvesting tool (login required).

Also, take some time to determine how changes in the value of your investments within your portfolio have affected your mix of investments. Routine portfolio rebalancing is recommended for keeping your portfolio aligned with your goals. It often provides an opportunity to reexamine lagging performers that could be candidates for tax-loss harvesting. For more on this, read Viewpoints. “Do rising markets mean rising risk? ”

Ideally, tax planning should be a year-round activity, and that includes tax-loss harvesting. Keeping good records will help you track your cost basis and anticipate any capital gains tax liability long before the end of the year.

Also keep in mind that selling a depreciated investment that no longer has a place in your portfolio can be a good move even if you don’t anticipate having capital gains to offset it. You can use the proceeds to invest in something with better prospects that may better suit your needs. The loss can be used to lower your tax bill through reducing ordinary income by $3,000, or carried over into future years if not needed immediately.

Learn more

- See whether you can help offset taxes on realized gains by selling currently losing investments with our tax loss harvesting tool (login required).