State Pensions Rethink HighFee Hedge Funds but Love Private Equity

Post on: 24 Май, 2015 No Comment

Photograph by Melanie Stetson Freeman/Getty Images

At the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, the biggest public pension in the U.S. 1.6 percent of the assets were invested in hedge funds

(Corrects the amount invested in a hedge fund in the second paragraph.)

Two basic principles of investing hold up remarkably well: Past results really don’t predict future performance, and high fees eat away at your returns. Smart investors don’t chase performance (as much as they can help themselves) and keep costs to a minimum. Unfortunately for taxpayers, the experts who run public pension funds aren’t following these rules. What’s more, they have little incentive to start.

First, the good news: Public pensions in California, Ohio, and New Jersey have been reducing their investments in hedge funds, noting high fees and poor performance, the Wall Street Journal reported. The Los Angeles Fire and Police fund invested $500 million in a hedge fund that returned less than 2 percent over the last seven years; the fund had comprised just 4 percent of Fire & Police’s portfolio but 17 percent of investment fees paid.

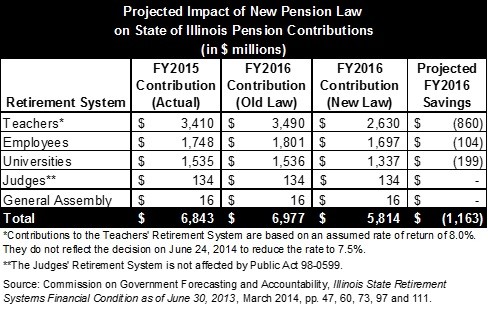

The pension plans reconsidering these high-fee, low-performance investments include those with allocations to hedge funds ranging from 1.6 percent to 15 percent of assets, according to the Journal. What they share, though, is dismal returns: The average hedge fund return for public pensions was 3.6 percent for the three years ended March 31, a period when returns from stocks were up more than 10 percent.

But for all the griping about hedge funds’ high costs and lousy performance, it doesn’t appear pension funds have learned their lesson: They are maintaining their investment in private equity, in some cases, even expanding it. Private equity funds invest in non-publically traded assets; like hedge funds, they also promise higher returns—in exchange for high fees and often more risk. And historically, private equity has been a bust for pensions, too. Research by economists Josh Lerner, Antoinette Schoar, and Wan Wong found public pensions underperformed in private equity relative to other institutional investors such as endowments, private pensions, and insurance companies. In the period they looked at (funds raised from 1991 to 2001), the pension funds’ private equity investments didn’t do much better than an equity index fund.

So why the preference for private equity? It sure looks like performance chasing. According to the Journal. private equity investments returned more than 10 percent to large pension funds in the last three years. Accordingly, pension funds have dived in.

Just 0.6 percent of Ohio’s state pension assets were invested in private equity in 2002. By 2013 it took up more than 9 percent. The California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) increased its investment from less than 1 percent to more than 12.4 percent of its assets between 2001 and 2013.

In 2013, Ohio celebrated its move: The five-year return on private equity was almost 12 percent—one of its best-performing asset classes. That means either pension fund managers have been luckier since 2001, more skilled, or private equity is having its day. Private equity is risky, and you’d expect high returns some of the time. The question is, can they keep it up?

Fund managers have every reason to be bullish. After all, they’re tacitly rewarded for chasing investments that promise higher returns. The funds use their expected return on their assets to figure out what they expect to owe pensioners in the future. The higher the expected return, the smaller their future liabilities appear. The only way to jack up the expected return is to pay for it, either by paying for access to more exclusive markets (like private equity) or by taking on more risk, or both. If pension funds invested only in low-cost index funds, it would be harder to justify the 7 percent to 8 percent return states currently forecast. This leaves pension fund managers with an incentive to constantly chase the latest, greatest, and most expensive assets.