Rethink Your Fixed Income Portfolio Strategy

Post on: 2 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Summary

- Many investors have locked in unattractive IRRs in their fixed income portfolios that make little sense after considering their investment time horizon and liquidity needs.

- Investors can estimate their expected future returns for fixed income portfolios by understanding the risk premia embedded in their portfolio. Unconstrained bond funds primarily just rearrange these risk premia.

- Investors can improve returns in fixed income portfolios by accessing the illiquidity premium through careful analysis of closed-end funds (CEFs).

Traditional Fixed Income Portfolios can no longer provide acceptable IRRs with low price volatility.

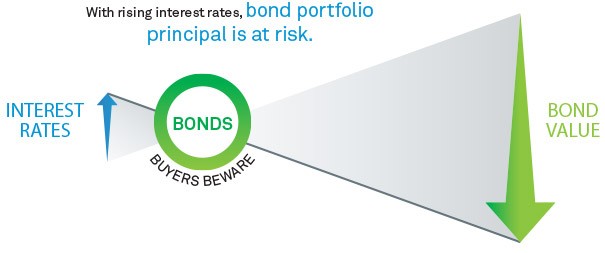

Family offices and individual private investors need to be asking hard questions when reviewing their current fixed income strategy. Many investors are currently making decisions with a myopic focus on the risk of short-term loss due to rate volatility or from rates rising. For investors who have managed fixed income portfolios during an environment of falling interest rates and have counted on a stable bond portfolio as a bulwark against volatile equities, the thought process often is Our bond allocation is for steady income, low volatility returns, and where we’re not supposed to lose money. The fixed income portfolio is supposed to be where the investor is in control and thus price volatility is bad.

The reality is today’s fixed income environment does not allow for acceptable returns without a healthy amount of price volatility and risk. Still, though, many investors cannot stand the idea of letting go of control of short-term price volatility in fixed income portfolios. It’s easier to hunker down and hope for higher rates. One example of this myopic focus is the recent surge of nontraditional/ unconstrained/ absolute return bond funds. It’s no secret that many RIAs and brokers have been recently advising their clients to reduce or even abandon their core allocation to intermediate bonds in favor of nontraditional bond funds. All of the sudden, since the fixed income sell-off of 2013, it has become a no-brainer to add a sizeable allocation to these non-traditional bond funds to protect against the always imminent rise in interest rates. Every wholesaler who contacts my office is pushing these funds hard now. Each eagerly tells me that they have had considerable success with this strategy and that most asset managers now consider an allocation to non-traditional bond funds to be an integral part of their balanced fixed income strategy. I think what they mean by this is that they, personally, have had success convincing their clients to turnover their portfolio and buy into a new fund, increasing their sales commissions. This is all well and good for mutual fund wholesalers, but investors need to do a better job of defining what success is for the portfolios they manage. And is success in fixed income investing even possible in this low rate environment?

Identifying success means defining what the investor’s long-term financial goals are and the spending needs associated with those goals. Crafting an Investment Policy Statement is an essential practice for developing a comprehensive understanding of an investor’s required return, risk tolerance, time horizon, liquidity needs, and tax considerations. After completing the draft of an IPS, it will frequently become clear that the best course of action is very different from the obvious advice a robo advisor would have given.

A common disconnect frequently occurs between the traditional obvious advice and the investor’s time horizon and liquidity needs. For example, an individual investor may be 5 years from retirement with a $2 million portfolio. He and his wife have a 30-year life expectancy. The investor wants to at least maintain the real value of the portfolio after inflation of 3% per year, while taking a distribution of 4% of the portfolio’s value ($80,000). A robo advisor may recommend a 40%/60% stock/bond portfolio. Let’s assume equities are volatile but will return 8% on average per year (I know that’s a stretch of the imagination for some) and taxes are 15%. Well, 8% x 0.40 x (1 — 0.15) = 2.7%, so equities almost take care of inflation. So, of course we put the remaining 60% in several intermediate bond mutual funds with an expected return of 2.5%, right? 2.5% x 0.60 = 1.5% (before taxes). But wait, rates are about to rise. We better shorten duration significantly by mostly reallocating to short duration and nontraditional bonds funds. Now, our expected return is 1.5%, so we throw in an allocation to high yield bonds to get our expected return back up to 2.5%.

What’s wrong with this picture? The portfolio was not structured to achieve the investor’s goals and return objectives. We treated $1.2 million (60%) of the investor’s assets as if he needed them in the next 5 years and locked in a 2.5% IRR over this time period before taxes. He was only planning to retire 5 years from now! At most, he needs one year’s worth of liquidity now ($80k) and maybe 2-3 years’ worth of liquidity ($160k — $240k) once he retires that can be invested in short-term instruments, probably brokered CDs. And again, his current time horizon is not 5 years; it’s 30 years that this financial capital needs to be invested for. The next several years of market volatility should have little effect on his ability to sustain the value of his portfolio over the next 30 years.

In the current rate environment, keeping 60% of this investor’s portfolio in predominantly low volatility fixed income instruments is highly questionable. A higher allocation to equities is likely part of the solution, but the investor needs to rethink his fixed income portfolio strategy. The current interest rate environment demands it.

Identifying expected returns

A healthy exercise is to identify the risk premia embedded in your portfolio and identify how well you are being compensated in returns over the risk free rate (now near 0%) for bearing those premia. A premium is a single-factor exposure that provides a source of time-varying returns. Those returns will vary (and may be negative) based on different economic environments, but measuring and separating different premiums is a helpful place to start when identifying expected returns and structuring portfolios going forward. This exercise is easier to do in the bond market than with equities for obvious reasons.

The two factor premia traditionally considered within fixed income include the interest rate risk (duration) premium and the credit risk premium. A variant of these premia is the carry-trade premium, which involves shorting low duration or lower yielding assets and going long higher duration or higher yielding assets. This naturally increases the expected returns and risk of the portfolio by increasing an investor’s exposure to the interest rate and/or credit premia.

Unfortunately, investors are not being compensated well to take either interest rate risk or credit risk in most cases now. A good proxy for the interest rate premium is the 10-year Treasury’s yield-to-maturity (YTM), which is currently at 2.50%. Most investors’ bond portfolios will have a shorter duration than the 10-yr Treasury though (approx. 8.5).

A good proxy for the credit premium is the BBB or BB option-adjusted spread over the comparable Treasury maturities, which currently provide a premium of 1.55% and 3.09%, respectively.

Determine what proportion of your fixed income portfolio is allocated to these two factors and where you are on the spectrum of each premia and that will give you a good estimation of your expected returns. Effectively, that is the internal rate of return (IRR) the market is providing you at the moment. This projected IRR is your total return before idiosyncratic factors a manager may take advantage of and fees. You do not have to pay anything (well probably 10bps) to access these returns/risk premia. The Vanguard Intermediate-Term Bond Index Fund will provide an IRR of 2.57% over the next 6.5 years approximately (duration is the appropriate measure of portfolio turnover). The problem with this picture is the coupon/yield is too low to keep your head above water in a 2013-like year. If rates rise 100bps over a year, you will probably lose 4% of your portfolio’s value if you are invested in this bond portfolio — and it doesn’t make any difference if you’re in individual bonds. So, what do you do? Most investors choose to shorten duration.

Shortening Duration Locks in Lower IRRs

Shortening the duration of a fixed income portfolio effectively lowers the interest rate premium or IRR an investor earns. Let’s use a Vanguard index fund as an example again since it’s representative of this section of the bond market. The Vanguard Short-Term Investment Grade Fund has a YTM of 1.59% and duration of 2.5, so the investor locks in a 1.5% IRR for the next 2.5 years approximately. The investor will earn less and is continually playing defense against the potential for rising rates (5 years and counting). The reality is all that has happened is the investor has locked in a lower IRR investment for a shorter time period, and is hanging their hope on a higher rate environment soon, which may or may not happen. Most private investors I know would find this IRR entirely unacceptable in the context of achieving their long-term spending needs.

Another way to shorten the duration of the portfolio is for the investor to hire a nontraditional/absolute return bond fund manager. Supposedly, this nontraditional, absolute return bond manager, who probably has a background running a fixed income hedge fund, will be able to near perfectly time interest rate movements and credit spreads to provide a high enough return over 2.5% on average in the next 6.5 years to justify his fees and some additional alpha. And supposedly, the investor will have talent to pick the equivalent of a successful fixed income hedge fund manager, rather than the hoard of other nontraditional managers who will likely underperform the Barclays U.S. Aggregate after fees and mis-timing interest rates and credit spreads.

And, you can bet that many will very likely underperform. There is nothing magical about a hedge fund/absolute return strategy that will lead to outperformance. Liquid fixed income markets that can accommodate billions of AUM are very efficient with hundreds of fixed income analysts scratching around for a few extra basis points to gain a competitive advantage. Assuming the average hedge fund manager can find enough truly idiosyncratic opportunities to cover their fees, what primarily is going to drive their returns is how they choose to rearrange risk premia. For instance, a very likely strategy is to hedge out most interest rate risk (duration of close to zero) by shorting Treasury bonds or futures, while simultaneously going long corporate credit, probably high-yield bonds. This is simply a credit spread carry trade designed to capture the credit spread premium discussed earlier. You are being compensated to carry credit risk, and like most carry trades, this one is susceptible to permanent losses if it needs to be unwound during an economic crisis when credit spreads invariably widen. It is a profitable trading strategy in most environments, but do recognize that for the most part we are just rearranging risk premia.

If you are considering an absolute return bond fund, a fair question to ask is do you have a historically good track record of picking hedge funds? Has this track record led to superior performance or equal performance with lower volatility? My guess is the overwhelming answer to this question would be No. I think that we will look back five years and the conversation on nontraditional bond funds will be very similar to the current conversation on hedge funds: more fees and nothing to show for it.

The fact is it’s incredibly difficult to select bond fund managers ex ante that will outperform significantly after fees. The risk factors or premia that define an investor’s portfolio are far more influential than the sum of small idiosyncratic tilts an individual mutual fund manager will take. Understanding these return/risk premia is a critical first step to understanding what a portfolio’s expected and required IRR is likely to be over an extended time frame.

How to Access the Illiquidity Premium

So, if a 6.5-year IRR of 2.57% in your fixed income portfolio is unacceptable, what are your options? Many investors have shifted their allocations increasingly to the high yield section of the bond market and into higher yielding dividend stocks. Depending on the client’s circumstances, both of these options can be very sensible, especially a diversified portfolio of high yielding dividend stocks if the time horizon is long enough. In the former case, the investor is taking advantage of a greater credit premium (higher risk), and in the latter, the even greater equity market premium.

However, what many investors have overlooked is a less visible illiquidity premium. The illiquidity premium is available across the capital structure, and like every other factor premium it varies across time periods. You cannot count on it each year, but over the extended life of a portfolio, you can count on it adding excess returns and compensating you for the risk of higher price volatility — all other things equal. The best example of the illiquidity premium is in the equity markets among small-cap and micro-cap stocks. However, fixed income markets also offer a sizeable, time-varying illiquidity premium. This return premium is difficult to access in open-ended mutual funds with daily liquidity at NAV and is non-existent (maybe even negative) in ETFs due to their constant need for liquidity.

The best way for individual investors to access this illiquidity premium is through closed-end funds (CEFs). The source of so many of the inefficiencies in the CEF market is due to CEF’s illiquidity and an initially unsophisticated pool of original retail investors who purchase the CEF at the IPO at the standard 5% premium to NAV. After the IPO, the CEF structure lends itself to capturing the illiquidity premium in several ways:

1) Because the pool of capital is not subject to redemptions, the Portfolio Manager can overweight illiquid securities significantly whereas an open-ended mutual fund must limit its allocation to these illiquid securities (i.e. structured credit: CLOs, ABS, non-Agency RMBS and CMBS) to a fraction of the portfolio or risk fire-sales in the event of heavy investor redemptions. The portfolio manager can plan further out without the constant distraction or worry over fund flows.

2) A CEF can obtain relatively cheap but moderate leverage through which it can execute attractive carry trades. Very few open-ended funds do this because of the potential for large redemptions.

3) Finally, because there is no liquidity at NAV, CEFs are routinely available at double-digit discounts to their underlying asset values. However, there is far more short-term volatility associated with the market price of a CEF than its NAV. The discount is what compensates a CEF investor for the extra volatility. These discounts were particularly abundant late last year following the route in fixed income securities.

A good example of how these structural advantages play out in the market can be found in comparing the TCW Strategic Income Fund (NYSE:TSI ) with the MetWest Total Return Bond Fund (TICKER: MWTIX ). TCW’s portfolio managers direct both portfolios with the support of the team’s deep bench of analysts. The TCW Strategic Income fund has been running the same strategy since March 2006 when it switched from a convertible bond fund strategy to its current growth and income strategy (broader mandate). The primary difference between the asset allocation of TCW Strategic Income and MetWest Total Return Bond was TSI’s substantially larger allocation to securitized products (77%), primarily ABS (46%) and Non-Agency RMBS (24%) (Source: Morningstar ). I ran a portfolio characteristics analysis on TSI in Bloomberg and 117 of the

390 fixed income securities did not price. 98% of the illiquid securities were Non-Agency MBS. Of those securities that did price, the characteristics are listed below. What should immediately stand out is the wider OAS available on the securitized debt, which was more than double the OAS available on Corporate Debt. That’s a portion of the measurable illiquidity premium.

Compare these option-adjusted spreads to MetWest Total Return Bond Fund’s allocation to securitized products (39%), including ABS (12%) and Non-Agency RMBS (8%) (Source: Morningstar ). Below are that portfolio’s characteristics:

Again much of the pricing for the securitized products was not picked up, but as a broad representation, these characteristics are informative. The lower OAS in securitized debt is likely due to a higher allocation to Agency MBS, but it is also many of the higher yielding illiquid Non-Agency MBS did not price and are not well represented.

There is a significant difference in how the talented fixed income managers at TCW are allocating temporary, liquid capital and permanent, long-term capital. The allocation to less liquid Non-Agency RMBS as well as other securitized products has been a significant source of outperformance for both funds relative to the Barclays U.S. Aggregate. TSI ‘s significant overweight to the securitized sector has allowed the CEF to significantly outperform the open-ended fund and the Barclays Aggregate across all reported time periods as of 6/30/14.

The TCW Strategic Income Fund is currently trading at a modest 5% discount to NAV with a distribution rate of 5.4% vs. the open-ended MetWest Total Return Bond Fund’s TTM yield of 2.5%. Neither fund currently uses leverage. A significant part of the TCW Strategic Income Fund’s success is its permanent capital base, but the CEF structure also creates a much higher level of market volatility (standard deviation) even though the underlying NAV standard deviation is far lower. TSI’s advantage is extremely obvious over the past 3 years (the beginning of a period of ultra-low Treasury rates) as the CEF’s NAV returns have generated by far the best Sharpe ratio and alpha, while the CEF’s market price return have blown away the open-ended fund’s performance and the Barclays U.S. Aggregate Index.

Three years is admittedly cherry-picking and too short of a period to judge performance, so let’s look at how TSI stacks up against open-ended funds and Barclays U.S. Aggregate over the last 5 years

Okay, that did not include the crash, so let’s go back 10 years now.

That should do it. I think the main takeaway here is that the CEF structure of permanent capital can lead to significant long-term advantages for investors who are willing to give up their control over market volatility. The need to maintain adequate liquidity to accommodate investors’ on-demand capital withdrawals and their emotional preferences for lower volatility can place a significant drag on long-term returns. The CEF structure avoids these pitfalls and allows investors to capture the illiquidity premium. However, an allocation to these CEFs also raises the bar on due diligence there’s a lot of junk to weed through.

For investors with a greater risk appetite, two CEFs that I think are very attractive currently are Brookfield Mortgage Opportunity Income Fund (NYSE:BOI ) and First Trust Intermediate Duration Preferred & Income Fund (NYSE:FPF ). Both funds have previously been covered in detail on Seeking Alpha here and here. and both yield north of 8% with double-digit discounts to NAV. Both CEFs were busted and orphaned after IPOs in 2013 and have exhibited stable NAV returns since then. FPF just slightly increased its distribution. I think that over the next several years, the IRRs on these two investments will be in the high single digit range, especially considering the current 10%+ margin of safety embedded in the current NAV discounts. It’s important to note that both these CEFs use moderate leverage to finance very profitable carry trades currently, but their duration exposure is quite attractive (BOI =

0, FPF =

5.5). In the case of FPF, rates would have to rise by

200bps before the Company’s margin of safety from its NAV discount was eroded.

Reasons Financial Advisors Avoid Busted CEFs

There are multiple reasons many successful financial advisors avoid busted CEFs. Below are a few:

1) Most financial advisors managing fee-based accounts use portfolio management rebalancing software that accommodates fairly seamless trading across funds that provide adequate liquidity (i.e. ETFs and open-ended mutual funds). Most CEFs do not have adequate liquidity in the secondary market to accommodate a large rebalancing across all of a large RIA’s portfolio models. Depending on the size of the trade, a RIA might have to deal with the headache of trying to fill an order over the course of a week for a CEF, instead of the next day liquidity an open-ended fund provides.

2) Advisors working on a commissioned basis (brokers) are heavily incentivized to only market CEFs at the IPO date to earn the traditional 5% commission off the top of the fund. As soon as the CEF begins trading in the secondary market, the only material way to make money off the client is advise them to sell at a small commission for whatever reason and/or buy into a new CEF IPO.

3) Most CEFs use moderate amounts of leverage and are marketed as Yield Co investments. That scares away many RIAs. There are structural issues unique to CEFs (fund’s leverage structure, UNII, return of capital, etc.) that add complexity to these funds. In my experience, most advisors are confused by these structural issues or are unwilling to take the time to research the sector carefully to separate healthy total return opportunities from Yield Cos holding suspect over-leveraged investments.

4) CEFs are simply not on most advisors’ radar screens. Wholesalers never pitch busted CEFs as actionable ideas. No one is going to throw a conference to talk about the latest strategies in busted CEFs. For most advisors, there’s simply no incentive to cover this space. out of sight, out of mind.

In conclusion, investors with the time and energy to devote to researching closed-end funds can pick up a sizable illiquidity premium. This strategy is appropriate for investors with at least an intermediate time horizon. Currently, there are good opportunities in the fixed income CEF space that enable investors to capture attractive mid-high single digit IRRs, but investors need to fully understand the associated risk premia providing these returns before putting their hard-earned financial capital to work.

Returning to our earlier example of the investor retiring in 5 years with a $2 million portfolio, if he could reallocate that 60% of his portfolio to best idea CEFs, what type of IRR could he count on? —Probably 5-10% long-term based on the examples discussed earlier. Yes, he is moving out on the risk curve, and yes, his portfolio will experience greater market volatility. But, that’s what it is going to take to achieve the required goal in this case.

Disclosure: The author has no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours. (More. ) The author wrote this article themselves, and it expresses their own opinions. The author is not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). The author has no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.