Price to Earning Ratios (P

Post on: 26 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

It is important for us to find out what the entire business is selling for. In other words, if I want to buy the entire company, how much should I pay for it? The “cost” of acquiring the entire business is called market capitalisation. It is calculated by taking the number of outstanding shares of stocks and multiplying it by the current price per share.

Market capitalisation = Number of outstanding shares x current price per share

Knowing this can keep us from overpaying for a stock. At one point during the period of the Internet boom, most dot com or technology companies had similar, if not higher market capitalisation than other blue chip companies which were decades old. However, a look at their earnings reveals that, dot com or technology companies were earning much lesser. In fact, some had not generated a single dollar of profit. Hence, it is important for us to have a way to measure share price together with earnings. One number that will help us knowing how much we are really paying for a stock is the Price to Earning Ratio (P/E). The price/earnings ratio, commonly identified as P/E, PE or PER (I will stick to P/E in this blog) is computed by dividing the market price of shares by their EPS.

Price over earning per share,

P/E =

For example, if the price of stocks is $8 and the EPS is $0.40, the P/E is 20 ($8 / $0.4).

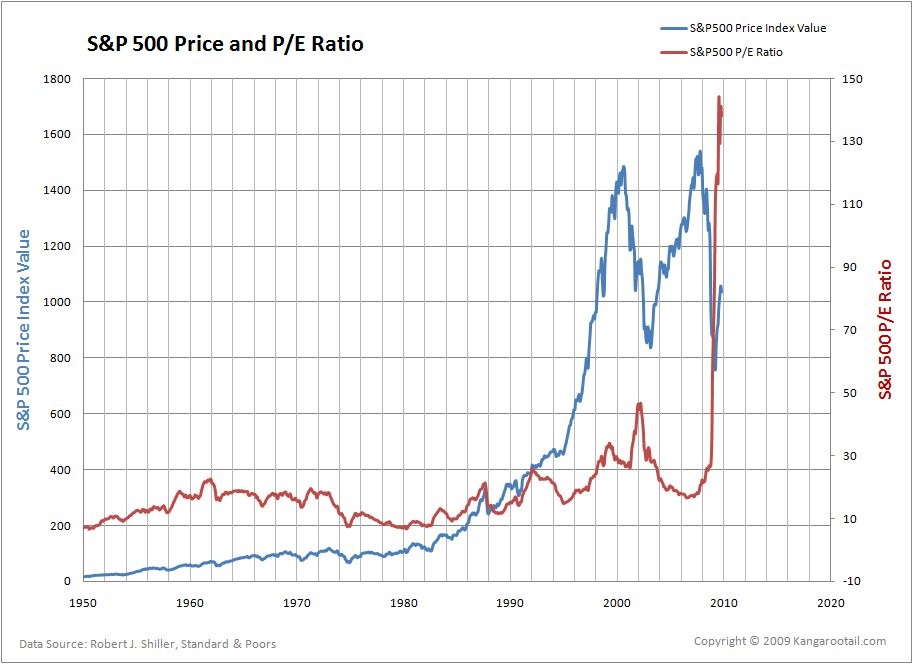

P/E can be considered an important ratio because it gives us a quick idea of how many times the price is a multiple of the earnings. P/E normally rises in tandem with the stock price, meaning that when the stock price rises, the P/E rises too, and vice versa, supposedly. In other words, shares purchased at a P/E of 30 means that the share price is 30 times larger than the current earning capacity of the share. That is, assuming the EPS remains unchanged (EPS growth rate is 0 percent every year), it would take 30 years for the earnings to equal the buying price. For instance, if the P/E is 30 and the EPS is $1 yearly, you will need 30 years to get back your $30.

Different analysts have different interpretations of P/E. So how do we interpret the P/E of a company? Let’s look at an example. Company A and Company B are in the same industry and have a P/E of 5 and 20 respectively. This means that:

- The market values the stocks of Company A at $5 for every $1 of its earnings whereas

- It values the stocks of Company B at $20 for every $1 of earnings.

One analyst may find that Company A is more attractive since it costs less for the same earnings of $1. A second analyst may reason that Company B is more attractive as a higher P/E means that the stocks are more valuable in that the company has a higher potential to deliver attractive returns. So, which is the best, a low or high P/E?

If stocks have passed the tests of ROE, EPS growth rate and D/E, the lower the P/E, the better the stocks. I will go for the lowest P/E.

Bear in mind, P/E can be reliable only if:

- The EPS is stable and does not fluctuate by a great deal. If year 1, EPS is $1, Then, it rose to $5 on year 2 before dropping to -$2 (making loss) in year 3. Something was taking place. You need to find out the reasons. I often do not consider invest in such stocks because it does not give the consistency I want.

- Remember that P/E = . Hence, the Earning per Share has to be within the positive range, which shows the company is not losing money; otherwise (when the company is losing money or not earning money), the EPS has a negative value. There are varying opinions on how to deal with this situation. Some say the P/E should be negative; others give it a value of zero (0) and the majority may say that P/E does not exist. I would not consider looking at a company which does not have earnings or an EPS until it posts a sustainable positive EPS. This has helped me eliminate unprofitable companies from my list of companies I am considering investing in.

Some people said that comparing P/E of companies is useful only if they are in the similar industry. I used to have the same thought too. For example, utility companies typically have low P/E because they have low growth but they are in a stable industry. In contrast, the technology industry is characterised by phenomenal growth rates and constant changes. Comparing a technology company to a utilities company is like comparing an apple with an orange. Only compare companies in the same industry, or to the industry average. However, for me, I still believe that we should go for lower value of P/E. I can never convince myself to buy stocks with P/E value of 40 just because it is a technology stock.

Some analysts provide a P/E range calculated using the highest and lowest value for a given year or period. I think this is fair. As with all other numbers (ROE, EPS growth rate, etc.), it is more valuable to look at P/E over time (past 5 to 10 years) in order to determine the trend.

Average P/E will allow us to relate the current P/E to the range of P/E experienced by the shares in the past. Ideal stocks must have a P/E which is at least below mid range. For instance, the average highest P/E of a company for the past 10 years is 30 while its average lowest is 10:

Average P/E =;

If these stocks were selling at a P/E of 22, I would not buy them. I would consider buying them when the P/E is lower than 20. This is not a definite number, but it provides me with a good baseline to evaluate the stock.

I have received many e-mails about the calculation of average P/E. Below is an example:

Year 2000: Highest P/E = 20; Lowest P/E = 10

Year 2001: Highest P/E = 40; Lowest P/E = 30

Year 2002: Highest P/E = 30; Lowest P/E = 20

Method 1:

Average highest P/E from year 2000 to 2002 = (20 + 40 + 30 ) / 3 = 30