Making Sense of Spinoffs EBAY HPQ TWX TIME PFE Investing Daily

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

By Chad Fraser on October 8, 2014

If you’ve been following the business news lately, you’ve probably heard a lot about spinoffs.

In fact, 2014 will see the largest number of corporate breakups in more than a decade. According to research firm Spin-Off Advisors, 62 spinoffs will likely be completed this year. To see a number higher than that, you have to go all the way back to 2000, when there were 66. This year’s expected total is also far ahead of last year’s tally of 37.

The trend looks like it will continue into next year, with a number of already-announced spinoffs poised to take effect in 2015.

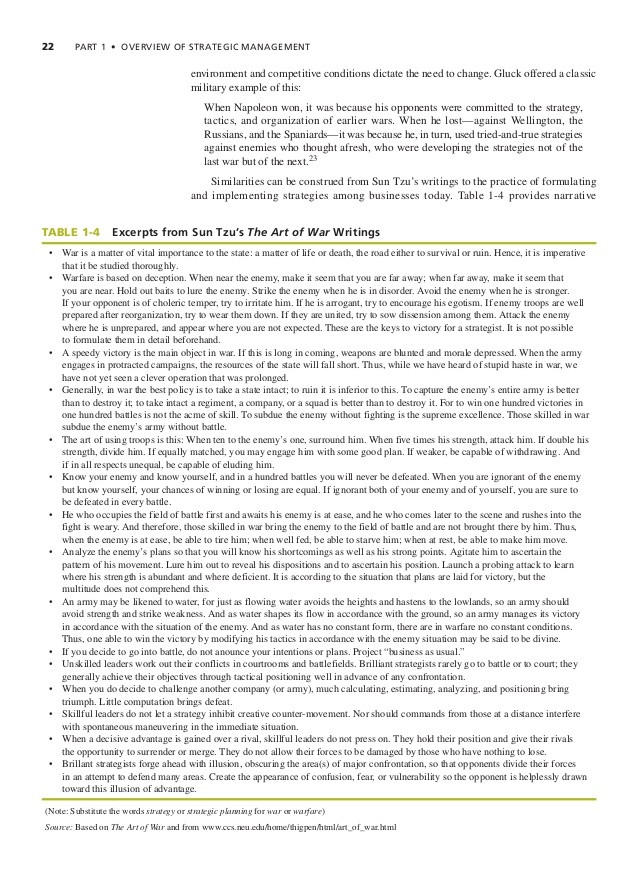

Among them are eBay’ s (NasdaqGS: EBAY) recently announced plan to set up its PayPal payment-processing business as a separate company and Hewlett-Packard’ s (NYSE: HPQ) just-announced move to split its PC and printer units off as a separate firm.

Further on, we’ll look at how spinoffs (and their parents) typically perform after going their separate ways, and whether a spinoff is a sign of a good investment.

But first, let’s take a closer look at how spinoffs work and why companies undertake them.

Spinoffs in a Nutshell

A spinoff, as the name implies, occurs when a parent company turns one of its business units into an independent firm. There are a couple different ways it can go about this.

The usual course is for the parent to distribute 100% of its interest in the subsidiary to its own investors as a stock dividend. Typically, shareholders don’t have to pay taxes on the shares of the new company they receive until they sell them.

A recent example is media giant Time Warner Inc. (NYSE: TWX). which completed the spinoff of its publishing business in June. Time Warner shareholders received one share of the new company, called Time Inc. (NYSE: TIME) for every eight Time Warner shares they held.

Another way a company can complete a spinoff is by letting its investors exchange their existing shares for stock in the new company, often at a discount.

Alternatively, a company could choose to carry out what’s called an equity carve-out, or partial spinoff, where it sells a minority interest in a subsidiary (usually less than 20%) in an initial public offering (IPO).

In these cases, the newly spun off firm enjoys greater autonomy from the parent (with its own board of directors, CEO and financial statements) but still maintains close ties, so it benefits from the parent’s expertise and resources. Carve-outs often result in full spinoffs later on.

One company that went this route is drug giant Pfizer Inc. (NYSE: PFE). when it divested its animal-health subsidiary, now called Zoetis Inc. (NYSE: ZTS) .

In February 2013, Pfizer sold roughly 17% of Zoetis in an IPO. Then a few months later, it spun off its remaining stake by offering its shareholders the opportunity to swap their Pfizer shares for Zoetis stock at a 7% discount, giving them about $107.52 worth of Zoetis stock for every $100 of Pfizer shares they exchanged.

Breaking Up Has Benefits…

Numerous studies have shown that both spinoffs and their parent companies tend to perform well following a split.

For example, a 2012 Credit Suisse study examined companies involved in spinoffs over the previous 17 years and found that, on average, newly spun off firms outperformed the S&P 500 by 13.4% in the first 12 months after the breakup, while parents topped the index by 9.6%.

There are a number of ways spinoffs can unlock hidden value. For one, they allow each firm’s management to zero in on its main business, something that investors—including activist investors—have been clamoring for in recent years.

“Over the past four or five years, there’s been a push toward corporate clarity and a push toward getting back to core businesses,” Robert Kindler, Morgan Stanley’ s (NYSE: MS) global head of mergers and acquisitions, told CNBC yesterday. “It’s institutional investors as much as activists who want to have companies focus on a core business.”

Accordingly, the new company’s management, freed from the former parent’s corporate structure, may be able to tap into new growth opportunities that were previously unavailable.

The PayPal spinoff provides an example. As a subsidiary, a certain segment of the fast-growing e-commerce market could be tough for PayPal to access, because companies like Amazon.com (NasdaqGS: AMZN) and Chinese powerhouse Alibaba Group (NYSE: BABA) are eBay competitors. However, as an independent firm, it’s now free to pursue opportunities like these.

“One of the objectives of this is to give PayPal maximum flexibility to work with whomever they would like,” eBay CEO John Donahoe said in a September 30 USAToday article. “How that works out we have no idea—but this allows PayPal that kind of independence and freedom.”

…But the Early Days Can Be Choppy

Something else to keep in mind: even though they tend to outperform in the longer term, shares of both a spinoff and parent can turn in underwhelming performances in the days after the split goes into effect.

For example, the Credit Suisse study found that spinoffs underperformed the S&P 500 during the first 28 days before moving ahead of the benchmark, while parent firms took 27 days to do so. By day 60, both the parent and spinoff had returned on average 2.2% more than the S&P 500.

There are a number of possible explanations for this weakness. For one, investors are receiving shares in the new company—not choosing to buy them—and may feel the stock is inappropriate for them, prompting them to sell. Moreover, there is usually scant analyst coverage of the newly spun off firm, and outside investors may choose to hold off until the stock establishes more of a history before jumping in.

“You tend to see weakness early on as people sell it, and they’re not familiar with the company,” Paul Hickey, founder of Bespoke Investment Group, said in an August 21, 2013, CNBC article. “After a couple of weeks, the child usually outperforms the parent by a wide margin.”