Macro Notes 4 Goods and Money Markets

Post on: 21 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

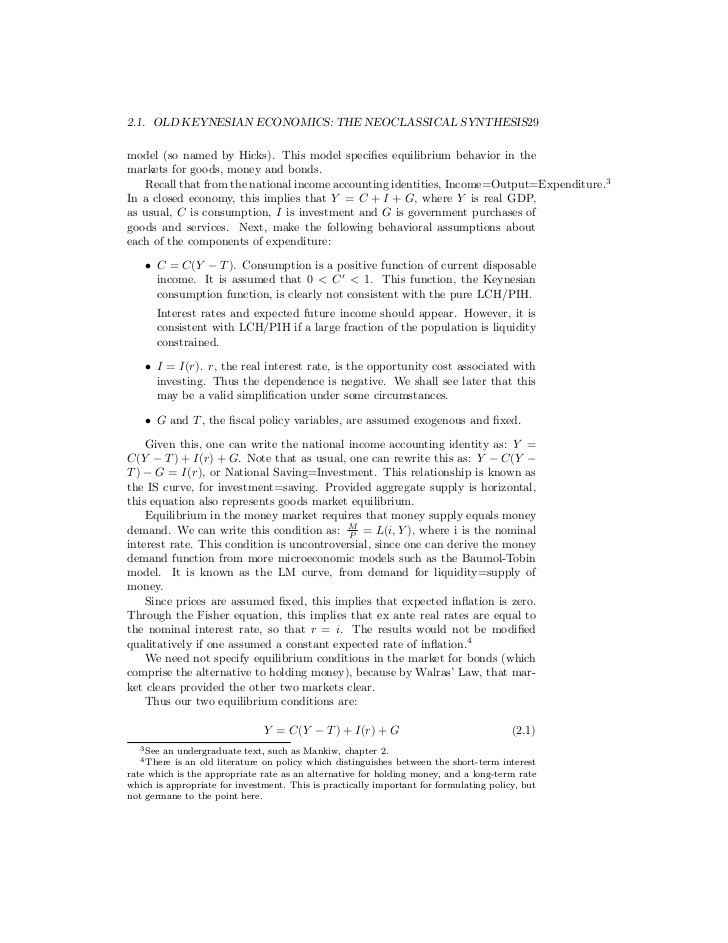

4.1 Interactions Between Goods and Money Markets

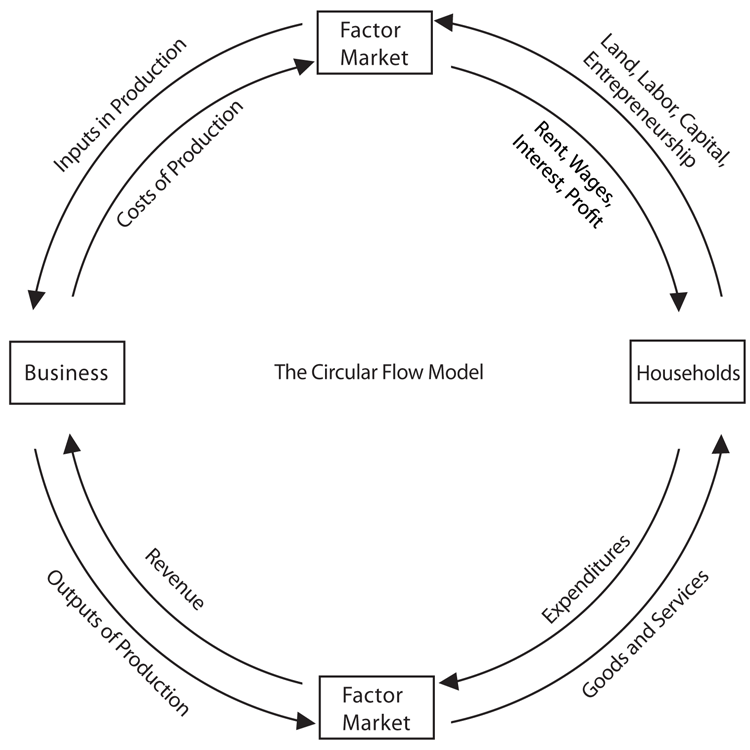

By Goods Market. we mean all the buying and selling of goods and services.

By Money Market. we mean the interaction between demand for money and the supply of money (the size of the money stock) as set by the Federal Reserve working through the banking system.

Now, once you have the goods market and money market firmly in mind, we can proceed to examine the interactions between the two.

Caution: Never use the word money for income or savings or investment, and never use the word investment to describe the purchase of stocks, bonds and financial assets. We need to be very careful with terminology because we want to carefully distinguish between what is happening in the goods markets (which describes a flow equilibrium between the production and purchase of real goods and services in a given year) and the money market (which describes a stock equilibrium between the demand and supply of money holdings and financial assets at a given point in time). The secret to doing well in this material is using words very carefully.

The interactions are very straightforward:

A. The money market determines the interest rate. The demand for money in the money market is affected by income (which is determined in the goods market).

B. The goods market determines income, which depends on planned investment. Planned investment in turn depends on the interest rate (which is determined in the money market).

Thus:

If something changes in goods markets and affects Y, this in turn will affect Md and hence affect r.

If something changes in money markets and affects r, this in turn will affect Ip, and hence affect Y.

That’s it.

4.2 The Interest Rate and Planned Investment

Back when we first set out the goods market, we had to leave Ip as fixed — exogenously set. Now, finally, we have a theory about why Ip might change.

The argument is as follows: interest rates reflect the cost of borrowing in order to finance investment projects. (Interest rates are not the only thing that determines decisions, but they are the variable we will focus on since they give us the links between the money market and the goods market). Other things being equal, as interest rates rise, it becomes more expensive to finance investment projects. Thus, as r increases, the number of investment projects planned will decline. This will reduce the level of investment expenditures in the goods market.

So Ip increases as r decreases, and Ip decreases as r increases.

A more extensive explanation would go like this: a firm may have a number of different capital investment projects in mind. If we assume that it can consider each one separately, and attach an expected rate of return to it with confidence, then at an interest rate of ten percent a firm will undertake all the projects that will generate a ten percent rate of return or better, but it will not borrow at ten percent to finance a project that will produce only a nine percent return. If the interest rate falls to eight percent, though, that project that offered a nine percent return now looks pretty good. So the lower the interest rate, the larger the amount of capital equipment firms will acquire, or the higher will be Ip.

4.3 Planned Investment and the Equilibrium Level of National Income

As shown above, as r decreases, Ip increases. Now as Ip increases, aggregate expenditures increase. And, as aggregate expenditures increase, equilibrium Y increases.

This works exactly like an increase in G: it’s additional demand for goods, which will call forth additional output of goods. As output (Y) rises C rises, which means even more demand for goods, more output, more C, etcetera. So the multiplier process will produce a larger change in equilibrium Y than the initial increment in Ip.

So we have the whole picture in place. When the Fed increases the money supply, it lowers the interest rate. This causes Ip to increase, and thus causes aggregate expenditures to increase. This in turn will set loose our multiplier and cause income to increase.

When the Fed reduces the money supply, this causes interest rates to rise, this in turn causes Ip to fall, and thus causes aggregate expenditures to fall. This is turn will let loose our multiplier process and cause income and employment to decrease.

Thus, expansionary monetary policy means that the Fed is either reducing the required reserve ratio, lowering the discount rate, or buying bonds. Any of these policies will increase the money supply, which should reduce interest rates and cause investment, and hence expenditures, and income and employment, to increase.

Contractionary monetary policy is when the Fed practices a policy of tight money. This involves either raising the required reserve ratio, raising the discount rate, or selling bonds. Any of these policies will reduce the money supply (hence tight money), which will increase the interest rate. This causes investment to fall, which in turn will cause expenditures, income and employment to decrease.

4.4 Impact of the Goods Market on the Money Market

We’re not quite done yet.

We’ve have looked at how the money markets affect the goods markets, but not examined the reverse in any detail.

The argument is: as Y increases, Md increases. As Md increases, ceteris paribus, r will increase.

Let us say that the government cut taxes. This will cause Y to increase. As Y increased in the goods market. Md increases, causing r to increase. As a result, Ip will fall.

Similarly if Y falls, Md falls. As Md falls, ceteris paribus, r will fall.

On the other hand if government spending were cut, the resulting lower Y would reduce Md, and r would fall. Ip would then rise.

(We also noted earlier that if the price level changed Md would change. We’ll get to price-level changes later.)

4.5 Interactions Between Fiscal and Monetary Policy

How the Effects of Fiscal Policy are Modified by the Money Market In section 1.10. when we described fiscal policy, we developed some simple multipliers without paying attention to the interactions between the goods and money markets. We now have to modify our discussion to take these interactions into account.

Let us start by assuming that the government undertakes expansionary fiscal policy to increase Y and hence to increase employment. Let us say the government increased G.

When the government increases G, we already know that aggregate expenditures, and hence aggregate income, will increase.

But, as Y increases, Md will increase. And, as Md increases, r increases.

This in turn causes Ip to decrease.

As Ip decreases, this dampens the impact of fiscal policy and income does not rise by as much.

The effect of fiscal policy on money markets causes the interest rate to rise and thus causes investment to fall. This is sometimes called crowding out, where the government’s expansionary fiscal policy can reduce investment and thus harm growth.

Note that these repercussion effects and crowding out would not happen if the fed had increased the money supply as Y increased, and thus prevented r from rising when the Fed does this, the Fed is accommodating the expansionary fiscal policy to prevent crowding out and to thus prevent fiscal policy from harming future growth.

Can you describe what happens when the government practices a contractionary fiscal policy?

How the Effects of Monetary Policy are Modified by the Goods Market As noted above, the Fed can affect the goods markets by changing the money supply and hence affecting r. This in turn affects Ip, which affects Y.

Suppose the Fed bought bonds and increased the money supply. As we know from our theory, this will cause r to drop as the money market seeks a new equilibrium. The drop in r raises Ip. As Ip rises, Y rises.

But: as Y rises, Md rises, and as Md rises, that will push r back up just a little. Therefore: r will not fall by as much once we take the interactions between the two markets into account.

Can you describe what happens if the Fed buys bonds?

4.6 Investment and the Interest Rate Revisited

Note that in the story of crowding out under fiscal policy, the key question that we have to address is exactly how much investment will change as r changes. In other words, the question of crowding out due to fiscal policy depends on the interest sensitivity of investment.

Similarly, for monetary policy the ability of monetary authorities to affect the goods market via monetary expansions depends on the extent to which investment responds to the interest rate.

Thus, in assessing the interactions between goods and money markets, the key factor that will determine the extent of the repercussions between goods and money markets will be the extent to which planned investment responds to changes in the interest rate.

Caution: Remember that we have been careful to use the word investment for one thing and one thing alone—the purchases of actual goods and services to increase future production. When we discuss the interest-rate sensitivity of investment we are examining whether the actual plans to invest in plants, machinery, and other such productive activities increases. This is not the same thing as asking, do people buy more or less stocks and bonds when the interest rate changes. So, don’t confuse the responses in the purchases and sales of financial assets with the interest rate sensitivity of investment.

While investment depends on the interest rate, it also depends on many other things. Two key variables that can determine planned investment are firms expectations about the future prospects for sales in goods markets, and the level of unutilized or underutilized capital they already have. If firms have a low expectation of future sales because they are nervous about a recession, or if firms already have a lot of unused production capacity, firms will not increase planned investment very much even if interest rates drop. Thus, the interest rate sensitivity of planned investment will depend on the expectations and capital utilization rates that firms have.

4.7 The Macroeconomic Policy Mix

As we have seen above, the government can use both fiscal and monetary policy to affect income and employment, though this may be easier said than done. In the United States fiscal policy (taxing and spending) is controlled by Congress, while monetary policy is controlled by the Federal Reserve, which is largely independent of Congress (or the Presidency).

Let’s run through the possible combinations:

a) Expansionary fiscal policy with contractionary monetary policy: this would help to boost demand and employment, but hurt investment and hence long-term growth. The extent of this impact depends on how sensitive investment is to the interest rate.

b) Contractionary fiscal policy with expansionary monetary policy: this should favor investment, since the combination of fiscal contraction and monetary expansion will lower interest rates. However, again, the net effect on income will depend on how sensitive investment is to the interest rate. If investment increases, but not enough to compensate for the drop on government expenditures, then income and employment will decrease.

c) Expansionary fiscal policy with expansionary monetary policy: as long as the money supply is increased by the appropriate amount to ensure that interest rates don’t rise, the fiscal expansion will cause income and employment to increase without hurting investment and growth: both G and Ip will rise.

d) Contractionary fiscal policy with contractionary monetary policy: the reduction in G lowers Y and also lowers Md which would normally lower r and boost Ip, but we also lower Ms at the same time so that r is not as likely to fall, and may even rise, in whihc case both G and Ip fall.

There is no hard and fast rule about the appropriate mix to follow. The correct mix will depend on how bad the recessionary pressures in an economy are, and how strongly investment responds to the interest rate.

But we can say this: if Ip is highly sensitive to r, then monetary policy is quite effective, and the monetary repercussions of fiscal policy will tend to dampen its effects. So if Ip is very sensitive to r, use monetary policy to change Y. On the other hand if Ip is not very sensitive to r then you’re better off using fiscal policy: not only will monetary policy be weak, but if you go with fiscal policy the dampening repercussions through the money market will be insignificant.

©1998 S. Charusheela and Colin Danby.