Is There a Biotech Bubble

Post on: 19 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

I’m bringing you a special Outside the Box today to address a very specific question that is on many investor’s minds: is there a bubble in biotech? To answer that question, Patrick Cox, editor of Mauldin Economics’ Transformational Technology Alert, teases apart the data on stock performance in the biotech space and then goes beyond the data to show us how the unique characteristics of the sector bear on the question of bubble or no bubble.

The answer isn’t a simple yes or no, but Patrick’s clear, deeply informed perspective can help us make smart investment decisions in an industry where both gains and losses can be precipitous and outsized.

Is There a Biotech Bubble?

By Patrick Cox, Editor, Transformational Technology Alert

FDA approvals for new drugs have accelerated over the last few years.

In 2013 alone, the FDA approved 27 new drugs. That followed a banner year in 2012, in which 39 novel drugs were approved—the most in 15 years.

Demographic trends will support the need for continued growth in the sector for years to come, as the aging US population increases demand for pharmaceuticals and other healthcare services. However, is this new paradigm enabling the growth potential of biotech firms or fueling the fire of yet another bubble?

A Brief History Lesson

The S&P 500′s biotech stocks are up more than 250% from the March 2009 bottom, versus a gain of roughly 180% for the rest of the market. This figure—although staggering on its own—does not include the hundreds of small- and mid-cap biotechs that have gone up even more.

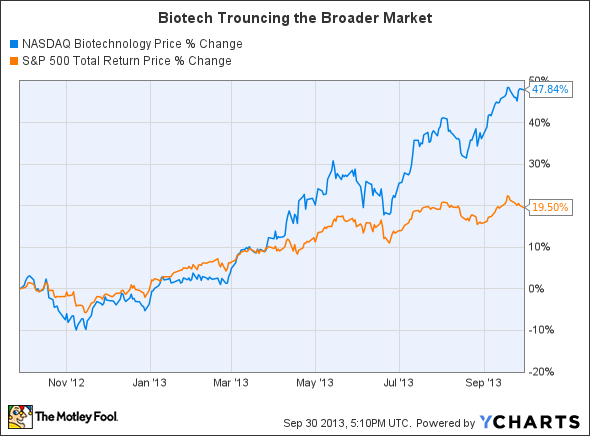

The Nasdaq Biotechnology Index, which does include some of these smaller names, gained 66% last year, double the S&P 500′s return. In fact, biotech was the #1 performing sector in each of the last three years.

Since 2012, biotech stocks also began a full-scale invasion and colonization of the healthcare sector.

For comparison, here’s a look at the percentage of biotech market-cap weighting in the healthcare sector SPDR (XLV) by year:

The pace of biotech stock growth is accelerating, but this isn’t enough evidence to say that we’re in a bubble. To properly label biotech’s rise and fall, let’s look at how the performance came about in the first place.

Numbers are being tossed about to show very high total returns, but they ignore the preceding sluggish period.

As shown below, biotechs were one of the laggard groups in the 2009-2011 period, outperformed handily by the Nasdaq Index, where the majority of biotech firms trade:

The chart above shows how the boom can be broken down into three phases:

- 2009-2011 = underperformance

- 2012 = catch-up performance

- 2013-recent = outperformance.

From 2009 through 2011, there was little to no public market capital for anything remotely risky, and so young biotech companies were forced to sell out to larger drug companies on the private market. This makes sense, as valuations on the private market were actually much better.

Meanwhile, as sluggish global growth persisted, investors began to favor large-cap biotech companies, such as Gilead, Pfizer, and Amgen. Unfortunately, there weren’t enough reputable biotech franchises to go around, thanks to a period of industry consolidation that included a buyout of Genentech by Roche for $46.8 billion, Merck acquiring Schering-Plough for $41.0 billion, and Sanofi taking over Genzyme for $20.0 billion, coupled with a shortage of public offerings. All the while, institutions took the remaining large biotech stocks to all-time highs.

Spreading the Wealth

In most markets, there are examples of both huge winners and terrible losers, and biotechnology is no different.

Here’s what the distribution of returns looks like for 172 US biotechs with a 12-month performance return:

While there were many small companies with monstrous returns, the returns were widely distributed, suggesting that this market is more selective than we would expect from a general bubble. However, it remains possible that many of these individual companies carry inflated valuations.

In the first quarter this year, there were about 50 IPOs; 45% of these offerings were for pre-profit biotechnology companies. In other words, they all lost money, yet they were valued at a median of $199 million.

Half of those biotech IPOs had no revenue at all. For those that did have some, the median 12-month sales amounted to only $200,000. That compares with median revenue of $125 million for non-biotechs with initial offerings.

However, although this may look fishy to the untrained eye, it’s not unusual for a small biotech company to have no earnings or revenue, as the company’s value is derived from potential future earnings and revenue from a product that’s currently in development.

That said, the bubbly part of this IPO market is that the average gain for these new biotech offerings is over 50%.

There has also been a spike in deal activity: last quarter M&A in the life-sciences sector spiked 24%, as 31 companies were bought for a total of $37 billion.

So yes, 2013 was a banner year for biotechnology IPOs—there’s no denying that. But when you look at the long-run trend, biotechs had been depressed for a decade. The truth is that there are hundreds of small startup companies that have great ideas, great products, and great futures, but they have yet to go public.

What’s lost in the hubbub about all these new IPOs soaring are two things:

- First, a lot of them have gone down in value, not up.

- Second, and more importantly, the surge in IPOs only reflects the shortage of biotech IPOs in the last 10 years. 35 or so IPOs in one year for biotechs may seem like a lot, but averaged out over the last 10 years, it’s nothing. Predictions are for another 35-40 to go public in 2014, for an annual total of almost 100.

From these mostly small, focused companies can come blockbuster, patented products. Once a privately funded biotech has reached a certain level in its development, an IPO can furnish it with the funds necessary to move through the next stages. Not all of these companies will be successful, but for the ones that are, the payoff can be large—even enormous—and that’s what keeps investors interested and willing to pay a premium for the opportunity.

Valuing the Biotech Market: One Size Does Not Fit All

Here’s the big picture via Brendan Conway of Barron’s:

“The price-earnings ratio of the SPDR S&P Biotech ETF is a rich 33 times trailing earnings, versus the S&P 500′s 17, says Morningstar. But Morningstar removes unprofitable firms from the tally. Add them back in and tally the losses against the prices, and the P/E multiple would be a negative 19, according to ETF.com’s Matt Hougan–if such a thing were possible.”

Some companies look more expensive and some look more reasonable today, compared to 2000. The real challenge with these companies is whether or not they’ll be successful in pushing their products through the pipeline and into the market.

Based on earnings forecasts, large-cap biotech companies including Amgen, Celgene, and Gilead are trading at 13.5x 2016 earnings and 11.7x 2017 earnings, which is cheaper than 14.2x and 13.5x, respectively, for the S&P 500. Of course, these are based on the assumption that the biotechs will recognize 21.5% annual earnings growth through 2017, versus 5.5% for the S&P 500—and both of these assumptions may prove to be too optimistic.

However, biotechs are often improperly “group analyzed.” Each company is in its own mini-field, at its own development stage, with its own potential return and risk outlook. Most currently listed biotechs have some sales, but few have positive earnings. Yet we read that the stocks are overpriced because the average P/E ratio is high. Here are the key statistics:

- All listed US biotechs = 215

- Some sales = 173 (80%)

- Meaningful sales (a price/sales ratio of 10 or less) = 45 (21%)

- Positive current earnings = 29 (13%)

- Positive estimated (forward) earnings = 35 (16%).

There’s a wide disparity among the 215 companies. Looking at market capitalizations, we can see a great divide between the few mega- and numerous mini-biotechs:

More to the point is the relationship between market cap and earnings yield (E/P). This graph shows the great number of money-losing, smaller biotechs.

Clearly, using a one-size-fits-all traditional industry analysis and valuation comparisons misjudges biotechs. Each company must be analyzed individually, as no two companies are addressing the same market with the same product and the same stage in their development.

But as a whole, the biotech sector still looks attractive when factoring in its growth potential. The price-to-earnings growth ratio (which is similar to earnings per share; however, it takes earnings growth into account) for biotech is around 0.7, around half the value of the S&P 500.

Broader Market Implications

Growth stocks are on their own tracks and will proceed according to their own developments and investor views.

In short, it’s beginning to look a lot like 1999 or early 2000, but not for the whole market or large-cap stocks. Those crucial areas could be overvalued after five years of enormous gains, but the numbers suggest that the overall Standard & Poor’s 500-stock Index compares favorably with the stratospheric prices that investors routinely paid in 2000.

In 2000, for the 10 biggest stocks in the S&P 500 by market cap, the P/E ratio was 62.6. Today, the comparable figure is only 16.1. Back in March 2000, Cisco had the highest P/E ratio among the 10 biggest stocks, at 196.2, followed by Oracle, at 148.4. Those figures were so high that when sentiment turned, the stocks plummeted.

Today, only one stock in the big 10 has a P/E above 30: Google, the sole Internet company in the group. Its P/E is 33, double the current average for the S&P 500’s 10 biggest companies, but compared with the levels that prevailed in 2000, it’s reasonably priced. If earnings grow rapidly, Google could conceivably be profitable for investors at its current valuation.

The point is that even if prices are high in the overall market, they’re being backed up by earnings to a much larger extent than in 2000. That’s important, because—as I’m sure many of you remember—when the dot-com bubble burst, the downdraft brought most companies down with it.

Moving Forward

Many of our subscribers have written to us asking how the most recent selloff will affect our analysis moving forward.

In short, not at all. We examine individual companies based on the merits of their technology. We evaluate the potential market value of their products and adjust for the probability that they’ll pass through clinical trials based on their particular stage of development. This results in a highly defensible valuation for the company that changes as the company’s products move through clinical trials.

The important factor that many analysts ignore is the probability for a product’s success, which varies by the clinical trial phase and therapeutic area. This, among other factors, is how many of the high valuations have been justified.

Our analysis, however, remains grounded in reality. Even the best companies can be priced too high or too low, and our recommendations focus on the best companies with the best risk-adjusted returns.