Is investing in Russia still a risky game of roulette Spend Save Money The Independent

Post on: 19 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Sceptical about investing in Russia, James Daley visits Moscow to hear the sales pitch

Just over a year ago, I sat down to lunch with one of Britain’s leading investors in Russia, Robin Geffen, who tried to persuade me of the merits of investing in the world’s largest country. As I reeled off a list of concerns, such as Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s megalomaniac tendencies, Russia’s refusal to cooperate in the Litvinenko investigation, and Putin’s handling of the Yukos affair (where the Russian government effectively seized a private company’s assets and sold them back to the state at a knock-down price), he sat back and rolled his eyes. For each of these objections, he offered an alternative and perfectly reasonable view of the situation, insisting that the Western media continues to ignorantly paint Russia in a bad light.

Yet, the more he objected, the harder I found it to buy his arguments. After all, as the manager of one of the only UK-based retail funds that invests in the region, he had more than a vested interest in talking the market up. And how could I ignore the scepticism voiced in numerous articles I had read in respectable magazines such as The Economist and newspapers such as my own?

Acknowledging my scepticism, Geffen vowed to take me, and a handful of other British journalists, to Moscow to see Russia’s promise for ourselves – and nine months later, four days after a Russian team had lifted the Uefa cup and on the very day that the national ice hockey team won the world championship, he made good on his promise.

Bust to boom

It is hard to dispute that Russia’s journey over the last decade has been remarkable. Since the devaluation of the rouble and the financial crisis that ensued in 1998, growth in Russia has steadily increased to almost match that of China and India. Last year, it recorded a real growth rate of just over eight per cent, maintaining its average of seven per cent annually over the past decade.

Equity markets in the country have performed even more impressively. Over the past five years, the Russian stock exchange has delivered average annual returns of more than 30 per cent, while Geffen’s fund – the Neptune Russia and Greater Russia fund – has trebled investors’ money since its launch at the end of 2004.

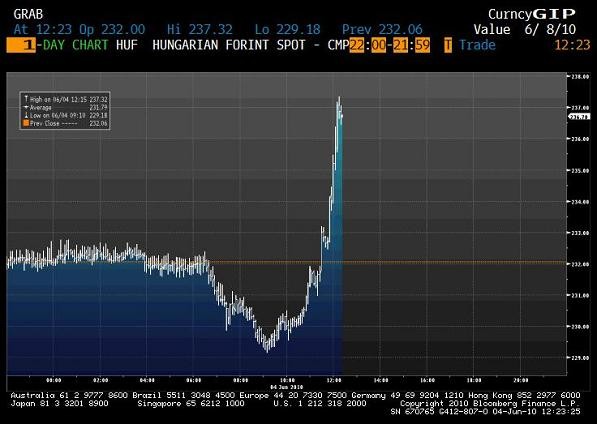

One of the main concerns among Western investors, however, has been the country’s dependency on oil and gas, which accounts for nearly two-thirds of Russia’s exports. This has been reflected in the stock market in recent weeks. Since the end of May, the Russian market has fallen more than 20 per cent, at first in anticipation of, then in response to, a fall in the oil price – which has dropped around 20 per cent in less than a month, to below $120 a barrel this week.

However, Elena Shaftan, the manager of Jupiter’s Emerging European Opportunities fund, which invests more than half of its portfolio in Russia, says Russia’s dependency on the energy sector is exaggerated. The economy is likely to be in a pretty healthy position, even if the oil price falls, she says. Around 80 per cent of growth today is driven by consumers and investment. So even if oil falls to $80 a barrel, the economy is still likely to grow at seven per cent.

Rise of the consumer

Anyone thinking of heading over to Moscow for a nice, cheap weekend should think again. I nearly choked on my beer when I was asked to pay £11 for a pint in my hotel – twice as much as you’d be charged in any of London’s Park Lane hotels. Such extortionate prices are a by-product of the small but growing number of super-wealthy Russians: Moscow is now home to more billionaires than any other city in the world.

But it is Russia’s expanding middle class that most excites Geffen and Shaftan. Russia has the eighth largest population in the world, around 140 million people – most of whom have been getting slowly wealthier for the past decade and are spending an increasing amount of their income on luxury goods, services and even holidays.

Unlike most other emerging markets, Russians much prefer their own brands to anything that the West has to offer. Hence, companies such as Wimm-Bill-Dann, which produces everything from fruit juice to baby food under brand names that’ll never see the light of day in Asda or Waitrose, have been growing at a great pace as consumers trade up to more expensive foods and drinks. The company has been a core holding in Geffen’s fund.

Though Shaftan has her reservations about Wimm-Bill-Dann, she has chosen to play the consumer boom by investing in vodka producers such as CEDC and Synergy, and the over-the-counter drug company Pharmstandard.

Similarly, domestic airlines, such as the national carrier Aeroflot, have huge potential as more Russians start to travel. Aeroflot has a domestic stranglehold, Geffen says. Domestic air travel – which we had assumed would grow at about nine per cent per annum – actually grew at 18 per cent last year, which is colossal.

Though Aeroflot suffers from the same image problem that car manufacturers such as Skoda once did, it has spent billions upgrading its fleet and now feels much like any other major airline (with slightly gruffer cabin staff). Over the last five years its shares have increased eight-fold, and Geffen has been along for much of the ride.

Natural Resources

Oil and gas play a major part in the Russian economy, accounting for at least one-quarter of GDP. But these are not the only natural resources to be found in abundance in Russia. The mining and production of precious and non-precious metals is an enormous industry in the country, with great promise.

During my trip to Moscow, I met the investor relations team at Polyus Gold, Russia’s largest gold miner. Polyus is developing new mines that it claims will more than treble its output by 2015. If it manages only half this, it will have been an amazing success.

Polyus, however, is a good example of a company that makes Western investors nervous. Its two main shareholders are oligarchs – each owns 25 per cent – who have fallen out in recent months, delaying the spinoff of the company’s exploration arm, which the management believes will release more value for shareholders.

To date, however, Polyus’s corporate governance processes have worked well. In April, when one of the oligarchs, Vladimir Potanin, tried to increase his influence in the company by changing its board structure, he was outvoted at a shareholder meeting, fair and square. And Geffen insists that the Russian government would not let either of the two major shareholders do anything to jeopardise the other private investors’ interests.

Politics

For most people, it is the politics of Russia that remain the biggest turn-off when it comes to investing – a state of affairs that has not been helped by the recent deterioration of relations between Russia and the UK.

Vladimir Putin’s move from President to Prime Minister in May, after serving the maximum two terms in the top job, has also been a bone of contention. Many believe that the new President, Dmitry Medvedev, is merely a powerless stand-in, with Putin holding the real power.

Russian observers beg to differ. Last month, when Prime Minister Putin announced an investigation into alleged overpricing by the Russian metal producer Mechel and publicly criticised both the company and its chief executive, Medvedev was clearly angered. Days later, the President made a speech calling on government agencies to stop interfering in business, and tried to reassure private investors that Mechel was not shaping up to be the next Yukos. Shaftan sees this as the first sign of a rift between the two leaders, and proof that Medvedev is no puppet.

When it comes to the Mechel case, Shaftan adds that, in her opinion, Putin is merely trying to tackle Russia’s soaring inflation, which is now well into double digits. She doesn’t believe it is likely to have any wider affects for other businesses, though she is keeping a watchful eye on the situation.

The Mechel affair epitomises the political problems of investing in Russia. While professionals such as Shaftan are relatively confident that Putin does not pose any great threat to the prosperity of the market, she concedes that situations such as these do nothing to encourage investor confidence. While his methods may be clumsy, Putin’s main objective is to make Russia richer and stronger, she says. Putin’s government is not driven by considerations of personal gain, nor is it about to revert to the Communist era. Although his objective of strengthening the country may cause some volatility in the short term, it is supportive of the long-term case for investing in Russia.

Neil Cooper of the Russo-British Chamber of Commerce also dismisses the suggestion that Russia’s politics pose any threat to the prosperity of foreign investors and businesses. Even as Britain and Russia have reached new lows in their post-Cold War relations, British businesses are prospering, Cooper says. The data shows Britain is doing better than it’s ever done before [in Russia], he says. I don’t think British investment in the country will be affected in any way by the problems we have. The relationship between Britain and Russia is too important. You only need to look at the number of Russians with investments in Britain – 50 per cent of premium properties in London belong to Russians.

Cooper insists that Russia’s managed democracy has in fact helped to provide the stability that every investor wants. He believes that the country’s biggest challenges at the moment are the poor state of its infrastructure, along with rising inflation, a shrinking population and an unwieldy bureaucracy.

Corruption is another major worry for investors, and on this point, most observers admit that there is still a problem – particularly among some of the smaller companies, whose accounts are not particularly transparent. However, Geffen disagrees that there is a problem when it comes to the Russian blue chips. The oligarchs have been rewarded by the share price for their increased transparency, he says. They’re not going to do anything to jeopardise that in the long-run.

The risk – where minorities might be treated badly – is in some of the small companies in non-strategic industries. Not surprisingly, Geffen adds that this risk can be mitigated by letting a professional fund manager pick the right stocks for you.

Is it for me?

My two days in Moscow, meeting the investor-relations representatives of some of the country’s largest companies, as well as independent analysts and lobbyists, certainly helped me frame a different view of Russia and understand the frustration of the likes of Geffen regarding the country’s portrayal in the Western media.

The growing strength of the consumer, and the continued reform of the country in general, undoubtedly offer great potential for investors. Nevertheless, the risks should not be underplayed. While all the signs are that President Medvedev wants to maintain Russia’s strong growth and to sustain the high levels of inward investment it enjoys, the political situation still feels finely balanced.

This is certainly not a market into which investors should be pouring their savings. But for those willing to take the risk, it is worth considering allocating a small percentage of a portfolio to a fund such as those run by Geffen and Shaftan, who know the market well enough to try to ensure that your money does not fall into an unexpected black hole. Investing directly in Russian securities is certainly a risky business.

Shaftan’s fund does not just invest in Russia but also across the rest of emerging Europe, in countries such as Turkey, the Czech Republic and Poland. Credit Suisse European Frontiers and JP Morgan New Europe – all of which invest around 60 per cent of their portfolio in Russia – offer similar diversification. Geffen’s fund invests only in Russia, but to date has had by far the best returns. JP Morgan also has an investment trust that invests solely in Russia, while Barings and Pictet offer Eastern European investment trusts. For more information on how these various trusts have performed, visit www.trustnet.com.

Unless you’re a sophisticated investor, it’s well worth taking financial advice before you invest your money. To find an independent adviser in your area, visit www.unbiased.co.uk.

James Daley was a guest of Neptune Investment Management in Moscow

Russia in numbers

* Population: 140 million (world’s eighth largest)

* Size: 17.1 million sq km (world’s largest)

* GDP: £640bn (world’s 11th largest)

* GDP growth rate: 8.1 per cent