Investing in the Mittelstand Home is where the capital is

Post on: 20 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

More exciting than a savings account

GERMANS are wary savers and investors, shunning houses, stocks and corporate bonds in favour of low-yielding savings accounts and stingy private pension plans. But even Germans are chafing at the euro zone’s ultra-low interest rates. Many of them are turning to a more daring and yet somehow comforting investment: small bonds issued by Germany’s medium-sized Mittelstand companies.

The Mittelstand comprises less a set of private, often family-owned firms and more an idea. Typically they are first-rate producers of banal industrial components, such as car locks or refrigerator compressors. Robert Wardrop of Cambridge’s Judge Business School surveyed Germans about their views of big companies, big commercial banks, small co-operative or savings banks and Mittelstand firms. The Mittelstand was by far the most popular, with the least variation in attitudes.

In this section

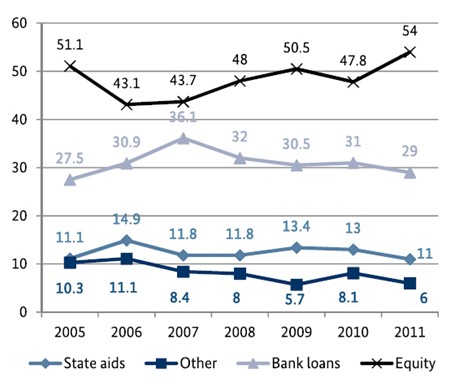

This came in handy when the credit crunch hit, leaving Mittelstand firms struggling to borrow from banks. In 2009 Klett, which publishes textbooks, raised €30m ($42m at the time) directly from small investors in just two weeks, with teachers particularly keen. Underberg, which makes a bitter digestive liqueur, raised €30m in 2014. These two at least have well-known brands. But other Mittelstand firms in obscure industrial niches have managed the same trick: Franken Guss, which makes car parts, raised €12m last year. The overall market of bonds issued by Mittelstand firms has grown rapidly since 2009, to an estimated €10 billion in 2013, including some Austrian and Swiss companies.

PCC, a chemicals group, was perhaps the first Mittelstand firm to tap this reservoir of goodwill, in 1998. It was forced to do so by Russia’s financial crisis that year, after which banks refused to lend to any firms with Russian clients, no matter how successful, according to Thomas Meuthen, PCC’s treasurer. Sixteen years later, it has made 41 issues of €500m in total to about 7,500 investors, some of whom have continued buying since 1998. PCC advertises the bonds on its website and through television ads, but Mr Meuthen says most buyers come via word of mouth.

Companies do not necessarily get better rates from small investors than they do from banks. PCC reckons it pays 2-2.5 percentage points more. But the bonds allow them to borrow when the banks are unwilling (or, due to their own financial problems, unable) to lend more—hence the boom in issuance since the credit crunch.

Intriguingly, Mittelstand firms have found that when British and German investors look at the same set of accounts, the Germans are willing to lend at lower interest rates. Mr Wardrop thinks that is due to their affection for the Mittelstand. He asked German buyers how they would define the Mittelstand ; they mentioned family ownership and humane management more often than the size of the companies or their legal form. Many feel that their banks, by contrast, are mercenary pushers of commission-driven products.

Ironically, something similar may be happening with Mittelstand bonds. Christian Hoppe of anleihen-finder.de, a website that helps individuals find bonds to invest in, worries that some companies are being convinced by advisers on commission to issue more debt than they need or can service. There have already been a few small bankruptcies, including that of Prokon, a renewable-energy developer.

Happily, ratings agencies specialising in Mittelstand bonds have sprung up; not all of them are given top ratings. But the appeal of investing in the Mittelstand will only really diminish if interest rates start rising again or Germans lose their faith in their economic model. Neither of those things seems imminent.