Industries Prone To Bubbles And Why_1

Post on: 13 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

A bubble (sometimes called an asset bubble, financial bubble or investment bubble) exists when the market prices of assets in a particular class far exceed those assets’ true value. These inflated values are unstable and eventually fall dramatically. (For more on bubbles, see 5 Steps Of A Bubble. )

Dozens of bubbles have inflated and burst over the course of history. While some bubbles appear to be one-time events, certain industries have seen bubbles form repeatedly, with investors seemingly never learning from past mistakes. Let’s examine a few of these industries and what appears to make them bubble-prone.

Precious Metals

In times of economic turmoil, many investors view precious metals as assets with intrinsic, long-term value. In the past, gold was used as currency or was used to back the value of paper currency; today it is not legal tender in the United States, but it still has valuable uses as a commodity in jewelry making, ornamentation, dentistry, electronics manufacturing and medicine because it is attractive, malleable and durable.

Throughout history, gold prices have largely been stable. Its average price per ounce in 1833 was $18.93. Its price hardly budged until 1919, when it moved up slightly to $19.95 an ounce. Through 1967, its price rose and fell incrementally, reaching a peak of about $35. In 1968, the U.S. government decided that its paper currency would no longer be backed by gold, and the metal’s price began to rise markedly. In the late 1970s, gold prices began to increase rapidly and by 1980, they spiked to $615.00 an ounce, but quickly fell and largely hovered in the $300s for the next 20 years. Not until 2006–2007 did prices return to the 1980 high; in 2011, gold reached over $1,500 an ounce.

Like gold, silver is also considered a safe store of value during difficult times. It also has numerous uses in both industrial and consumer goods. Since 1975, there appear to have been two bubbles in silver: one that peaked at $49.45 in 1980 and one that began in the late 2000s and was still inflating at the time of publication. After the sharp 1980 increase, silver’s price fell to around $5 by 1982. It hovered around this level until 2004 when it began to climb again.

Precious metals must be mined from the earth; they cannot be manufactured. Some metals are rarer than others, but in general, their limited supply helps to support their prices. Precious metals can also act as a hedge against inflation. (For further reading, see A Beginner’s Guide To Precious Metals .)

New Technology

Investors throughout history have become overly excited by the prospects of new technology. You know what happened with Internet stocks in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but do you know about the technology bubbles that preceded the dot-com bubble ?

The railroad industry provides an early example of a new-technology bubble. The first railroad began operation in 1825. In the 1840s, a rapid run-up in the prices of railroad company shares began. The average price of railroad shares doubled in the United Kingdom over a three-year period; a crash ensued in October 1845.

A telegraph bubble followed the railroad bubble. In his book, Pop! Why Bubbles Are Great for the Economy, Daniel Gross writes that from 1846 to 1852, the United States saw an increase in telegraph miles from 2,000 to 23,000. Too many lines were built, causing prices and telegraph companies to tank, with the exception of Western Union. Investors in companies such as the Illinois & Mississippi Telegraph Company and People’s Telegraph lost large investments.

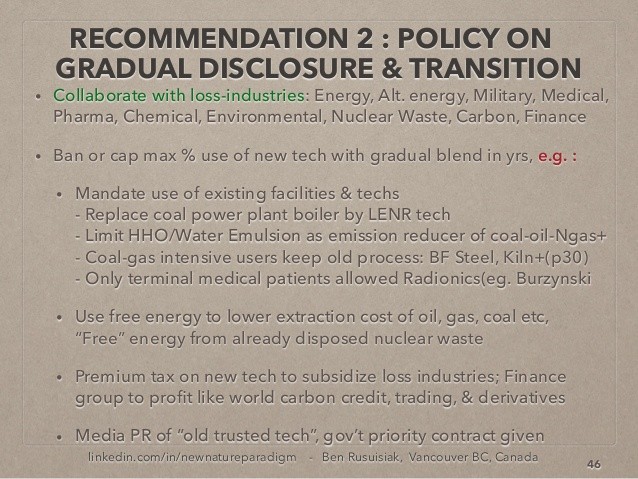

There are some indications that green technology (such as solar panels, wind mills and biofuels) and social media (such as Facebook, LinkedIn and Groupon) could be the bubbles of the future. Goldman Sachs valued Facebook at $50 billion in January 2011; in June 2011, CNBC reported that the company could be valued at $100 billion in a 2012 IPO. Both categories of new technology promise to change the world and have investors in a frenzy despite being relatively new and unproven. (Innovations in energy and consumption grow as companies adopt them to reduce costs. For more, see Clean Or Green Technology Investing. )

Collectibles

While not technically an industry, collectibles are a category of consumer goods that are sometimes driven to irrationally high prices that later crash.

In a June 2011 article in the Weekly Standard. Jonathan V. Last describes the comic book bubble that inflated throughout the 1980s. New comic books appreciated far above their cover prices within months of their release; famous back issues sold for tens of thousands of dollars in auctions at Christie’s and Sotheby’s. Comic book producers created dozens of new series and increased comic book prices, and new comic book stores opened across the country. When the bubble burst in 1993, comic book values plummeted, stores closed and comic book companies scaled back production. Marvel even filed for bankruptcy in 1996. The value of the most highly prized comic book issues has rebounded since the crash, but the comic book industry remains fundamentally changed. Comic book sales have continued to decline, though action figures and movies based on comic book themes have performed well. (A bankrupt company can provide great opportunities for savvy investors. For more, see Taking Advantage Of Corporate Decline. )

The 1980s also saw the formation of a bubble in baseball cards. Value stock analyst and financial editor Tracey Ryniec describes the baseball card bubble on her website, Tracey’s Market Update. Rookie cards began to fetch increasingly high prices, especially Mickey Mantle’s 1953 Topps card, which sold for $46,750 in a Sotheby’s auction, according to a 1992 New York Times article. Card production increased, baseball card shows started popping up everywhere and baseball card stores proliferated. Values of new cards rose and fell with players’ performance; cards purchased as part of a 25-cent pack could be sold for $100 if a player became successful and the card was in top condition. Eventually, too many new cards flooded the market, card prices declined and people lost interest; the bubble burst in the mid 1990s.

Beanie Babies — small plush animals produced by the Ty company — were a craze in the mid-to-late 1990s. They first became available in 1994 and retailed for $5 to $7 apiece. The company was able to cultivate an air of scarcity for the toys despite their mass production by selling them only through specialty toy stores and gift shops instead of through mass retailers, by varying production quantities and by regularly but unpredictably retiring, or ceasing the production of certain figures. In addition to scarcity, each plush figure had a name imprinted on the inside of a folding Ty tag that hung from the animal’s ear, and the tag had to be in mint condition for the toy to collect top dollar. Almost everyone bought these stuffed animals for their perceived collectible value rather than as toys. The Beanies that truly were rare fetched hundreds and even thousands of dollars in eBay auctions during the boom. By the early 2000s, however, people had lost interest. Most of the toys became worthless.

Real Estate

Everyone is familiar with the concept of a real estate bubble. What some people don’t realize is that while the 2000s real estate bubble was unique in its magnitude, it was not a unique phenomenon.

In a February 2011 New York Times article, economist Robert Shiller writes about two of the earliest real estate bubbles in the United States: the land bubble of the 1830s, which culminated in the Panic of 1837 and a major depression, and the land bubble of the 1850s, which culminated in the Panic of 1857.

John Simon describes the 1880s land bubble in Melbourne, Australia, in his article, Three Australian Asset-Price Bubbles. Wealth attained during the gold rushes combined with improved transportation, telephones, electricity and population growth to fuel demand for land in Melbourne’s suburbs. From 1874 to 1891, home prices nearly doubled. Then prices fell by more than half as much as they had risen, on average. In some areas, prices dropped significantly further. (For related reading, see Why Housing Market Bubbles Pop. )

Florida saw a real estate bubble in the 1920s. FloridaHistory.org and Linda K. Williams’ article, South Florida: A Brief History describe the boom and bust. In the early 1900s, the state’s population increased dramatically in percentage terms. Another factor driving demand was that travel had become easier and disposable incomes had increased, so Americans could come to Florida from anywhere in the country to buy real estate. Speculators also invested without ever setting foot in the state. Orange groves and swamps were auctioned off for real estate development and prices skyrocketed. Prices began to decline in 1925, and the boom’s fate was sealed when a major hurricane hit in September 1926 and the Great Depression followed not long thereafter.

What makes real estate bubble-prone? Seemingly every factor that can contribute to a bubble plays a role in real estate bubbles. Investors borrow money at low interest rates ; they use large amounts of leverage when purchasing property; government policies such as the mortgage interest tax deduction and the government backing of mortgage loans make real estate artificially cheap; and, as Shiller and fellow economist George Akerlof pointed out in their April 2009 article, How ‘Animal Spirits’ Wrecked the Housing Market, investors can easily convince themselves that rising real estate prices will rise forever because, since there is only so much land, population pressures and economic growth should inevitably push real-estate prices strongly upward. Real estate seems like a safe, logical investment: b oth developed and undeveloped lands have obvious, tangible uses such as mining, agriculture and housing.

What Goes Boom Must Go Bust

Why do bubbles keep recurring in certain industries? Even though historical bubbles often have much in common with present-day bubbles, investors often believe that things are different, that some sort of fundamental shift has occurred to make the most recent run-up in prices a permanent change. Investors who want to avoid being victims of future bubbles should look at what has happened in the past and consider the possibility that maybe nothing has really changed. (For related reading, see Riding The Market Bubble: Don’t Try This At Home. )