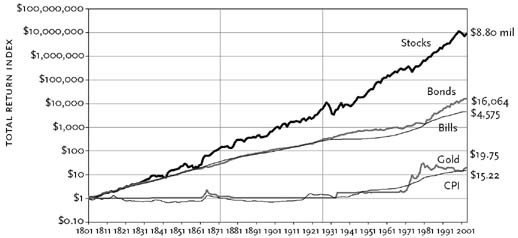

Historical Stock Returns Stocks

Post on: 5 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Source: Ibbotson Associates

Source: University of Michigan

In the 1990’s the New York Stock Exchange-where the stocks of about 3,000 companies are traded among investors each day- had its longest bull market (a period of rising stock prices) in its history. The NASDAQ-where the stocks of approximately 3,300 companies are traded- also experienced record performance. Following a sustained period of rapid stocks/shares value growth, it takes time during the downturn for memories of disappearing paper profits and high profile corporate failures, to fade. So the scenario for the foreseeable future is unspectacular average equity returns growth compared with successive years in the 1990’s of double-digit growth. However, some sectors and regions will continue to outperform others. In a long period down/bear market, there are always periods of growth. So the timing of stock market investment is important. The last protracted bear market (period of falling prices) in US equities started in February 1966 and lasted until August 1982. The Dow Jones index value in February 1966 was 995 and 16 years later it stood at 777. So any investor who stayed fully invested in an average portfolio of shares in this period lost 22%. Yet over this time span there were four periods in which equities experienced strong rallies which boosted the Dow by 32%, 66%, 76% and 38% respectively.

According to Stocks, Bonds, Bills and Inflation 2000 Yearbook. � 2000 Ibbotson Associates, Inc. while returns grew by an 11% average in the period 1926-1999, in the 5 year period 1972-1977, the stock market lost an average of 0.2% per annum.

According to a University of Michigan study, an investor who stayed in the US stock market during the entire 30-year period from 1963 to 1993-7,802 trading days-would have had an average annual return of 11.83 %. However, if the investor missed the 90 best days while trying to time the market, the average return would have fallen to 3.28% per annum.

According to Dr. Bryan Taylor of Global Financial Data, analysis of US bull and bear markets in the past has always used the S&P Composite Price Index, not the Total Return Index. Since most investors have their money in funds that reinvest their dividends, using a price index to determine the movement of markets does not reflect the results that investors receive. Over time, price indices produce dramatically different results from return indices. The 1920s bull market peaked on September 7, 1929. If someone had invested their money in the stock market on September 7, 1929, it would have taken until September 1954 to break even using the price index benchmark but on a total return basis (allowing for dividends), the investor would have broken even nine years earlier, in 1945. Total returns reduce the size of the falls in a bear market and increase the returns in a bull market.

The Global Investment Returns Yearbook (originally known as The Millennium Book ) was launched in 2000. It is produced by London Business School experts Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton in conjunction with ABN AMRO. ABN AMRO distributes the Yearbook to investment professionals and London Business School makes it available to other users (for more information, contact: Adrian Rimmer Tel: +44 (0) 20 7678 4050 Email: adrian.rimmer@uk.abnamro.com )

The core of the Yearbook is provided by a long-run study covering 106 years of investment since 1900 in all the main asset categories in Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. These markets today make up over 92% of world equity market capitalisation. With the unrivalled quality and breadth of its database, the Yearbook has established itself as the global authority on long-run stock, bond, bill and foreign exchange performance.

The paradigm that equity markets supported by strong currencies provide superior returns compared to equities in weak-currency markets has been rejected by the authors of the 2006 ABN AMRO Global Investment Returns Yearbook.

The Yearbook, published annually in partnership with Professors Dimson, Marsh, and Staunton of London Business School, is the most comprehensive and authoritative work of its kind and examines total returns since 1900 for stocks, bonds, cash and foreign exchange in 17 major markets, covering North America, Asia, Europe and Africa.

This years study takes a close look at the role of currency exposure in portfolio management and challenges the widely held view that equity markets supported by strong currencies will produce favourable returns.

Using data since 1900 for all 17 countries and also for a broader sample of 53 countries, the authors show that instead, equity markets experiencing currency weakness are more likely to outperform.

Chart 1 ranks countries by their exchange-rate change over the preceding 5 years, assigning each country to quintile portfolios. The portfolio comprising the weakest-currency markets performed best over 106 years and (using a larger sample of countries) over the last 34 years.

Professors Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton of London Business School, said:

Our preliminary long-term evidence shows that over the long haul, equity returns have not been bolstered by currency strength. Historically, avoiding weak currencies might have been justifiable to control risk, but not to enhance performance.

The Yearbook also shows that while currency fluctuations, such as the dollars strength in 2005 or its substantial fall over 200002, can seriously impact short-run equity performance, exchange rate movements have mattered much less to long-term investors.

This is because, over the long haul, parity changes have largely tracked relative inflation rates. Over more than a century, real exchange rates, after adjusting for differences in inflation rates, have changed at most by a mere fraction of one percent per year.

The Yearbook also shows the impact of currency volatility on the total risk of investing in overseas equities, and quantifies the gains from hedging.

Professors Dimson, Marsh and Staunton explain:

A key strategic issue for global investors is whether to hedge their foreign-exchange exposure. Our analysis shows that while hedging reduces risk, the gains from risk reduction have declined over time and are now modest compared with the gains available from diversifying equity portfolios internationally.

The Yearbook also looks more broadly at investment returns in 2005 as well as long-term trends.

Findings include:

- 2005 proved an excellent year for equities, with positive returns in all countries except China.

The US disappointed with a mere 6.3% return, compared to the majority of markets that exceeded 20% returns

- UK and Japanese equities posted their best performance since 1999 with respective returns of 21.3% and 45%. Germanys recovery is starting to translate into equity performance, returning 28% in 2005

- Mid-cap stocks outperformed their large and small counterparts in 2005. The mid-cap FTSE 250 index posted a 30.2% return, versus 20.8% for the FTSE 100 and 28.6% for the Hoare Govett Smaller Companies Index. In the US, the S&P 400 Mid-cap index returned 12.6% compared to 4.9% for the large-cap S&P 500 and 7.7% for the S&P 600 small-cap.

- Since 2000, small-cap stocks and value stocks have outperformed large-caps and growth stocks by a substantial margin in most countries.

- Despite strong equity returns in 2005, and cumulatively, since the bottom of the 2000-03 bear market in March 2003, world equities still show the scars from the bear market. The annualised equity returns over the 21 st century to date (2000-05) remain negative in 7 out of the 17 Yearbook countries, including the UK (-1.3%), the US (-2.7%), Germany (-4.1%), the Netherlands (-5.4%), France (-1.6%) and Sweden (-0.7%). The return on the world index was -1.2% p.a.

- Equities have outperformed government bonds and Treasury bills in all 17 stock markets, over the long term (chart 2).

ABN AMROs Head of European Equity Strategy, Rolf Elgeti, discusses the practical implications of the Yearbooks findings for equity investors in a forward-looking chapter. He sees two opposing forces when analysing the effect currencies have on equity markets.

First, a weak domestic currency is generally assumed to increase corporate earnings in that country as export opportunities improve as a result of increased competitiveness. However, this effect has been much weaker than many people believe. Export-driven German equities for example have experienced good returns, despite the strength of the Euro, returning 28% in 2005.

Second, a depreciating currency tends to increase inflation and, more importantly, inflation expectations. This can translate into negative effects on a companys stock-market rating, however the lower PE multiples that tend to follow weaker domestic currencies have historically been more than compensated for by higher earnings generated by currency depreciation.

Rather than taking a macro approach toward equity market investment, Mr Elgeti believes the best opportunities lie at the stock and sector level.

While a weak currency tends to lead to higher domestic earnings for export-sensitive equity markets, the effect on earnings for closed economies, such as the US, is more muted. The negative effect of a weak currency on overall market valuation and the positive effect on earnings may also broadly cancel each other out. We therefore believe that investors concerned about earnings should look at currencies as a factor for particular sectors and stocks, but not when looking at the whole market, he said.

IRELAND

The Dow Jones Industrials Average is based on 30 stocks of leading companies and represents about 25% of the New York Stock Exchange market capitalisation. The S&P Composite represents about 75% of the markets capitalisation.

Click for DJIA Jan 12, 1906 to date + record declines