Guest post The risks of buyandhold investing

Post on: 8 Май, 2015 No Comment

Or, How Pop enraged some of his readers.

This is a guest post by Rob Bennett, who writes about value investing at PassionSaving.com. But lets get real, that kind of standard introduction isnt enough for somebody the likes of Rob. In fact, Im fairly sure a certain number of you spit out your morning coffee when you saw that badly colored avatar at the top of the post (colored by me, by the way).

For those of you unfamiliar with Rob, hes a regular on pretty much every personal finance blog that mentions investing and hasnt banned him. Hes made it his crusade to up end buy-and-hold investing in favor of value-oriented strategies. But so far, its been done in such an odd way (blog comments that are longer than articles, a conspiratorial tone, oddly capitalized words as if he were writing in the Bible) that many bloggers, commenters, and passive readers simply hate the guy.

Its reached the point that he has at least one discussion board devoted entirely to making fun of him. Ironically, his detractors, who have spent hours writing posts about Rob, dont seem to see that their zeal has made them seem equally insane. Rob keeps giving them material. They keep giving him attention. And the fire burns on.

But lest I discredit Rob before hes begun, let me back up by saying that many of Robs arguments in favor of value investing actually make a lot of sensein a way that should make any rational buy-and-holder uncomfortable. This is Rob, edited. Only what I see as his best arguments against buy-and-hold made it in here. And in the end, Im sticking with my original argument. for all the behavioral reasons I listed in that post.

Enjoy. Or claw your eyes out. But trust me, its worth questioning your assumptions every once in a while.

Buy-and-hold masks investing risk

When I argue that investors need to change their stock allocations in response to changes in valuations, people often say its not possible with the tools we have today to know precisely how much of an allocation shift is best. This is so. The tools we have today are far more effective than most people realize. But theyre not perfect. Its entirely possible that investors following valuation-informed strategies will make mistakes.

But what of it?

There are no perfect investing strategies available to us. And we need to do something with our money. So we simply have to accept that, whatever path we choose, theres going to be some risk of making mistakes.

I believe that the reason why this concern evidences itself so often is that the popularity of buy-and-hold causes many investors to hold it to a lower standard than alternative strategies. Human psychology is such that things that are popular seem safe (this is why “As Seen on TV!” is an effective marketing slogan). Logic, however, doesnt support the idea that sticking to the same stock allocation at all times is somehow safer than making reasonable efforts to shift your allocation effectively in response to dramatic price swings.

To understand why, I think it might help to consider how safe driving an automobile down the highway would be if we decided on the speed we were going to travel in the way in which many investors decide on their stock allocations. Say that you read a book entitled “Driving for the Long Run” and became convinced as a result of the arguments set forth in it that the thing to do is always to remain at a single speed regardless of the driving conditions you faced in various circumstances.

Perhaps you would decide on a driving speed of 65 miles per hour. That would work well on sunny days. But what would happen the first time you happened to be out on the highway during a snowstorm? The rational drivers would slow down to 10 or 20 miles per hour, but you would stick defiantly to 65, likely killing yourself and a good number of others. Staying the course at the other extreme, or even picking a middle ground, would be just as insane.

The same can be said of going with the same stock allocation at all stock valuation levels. You can tell whether stocks are expensive or a bargain by looking at the markets price divided by the average of the past 10 years of earnings (P/E10). Using 10 years worth of earnings for the P/E rather than the usual one year smooths out unusual drops or bubbles in earnings.

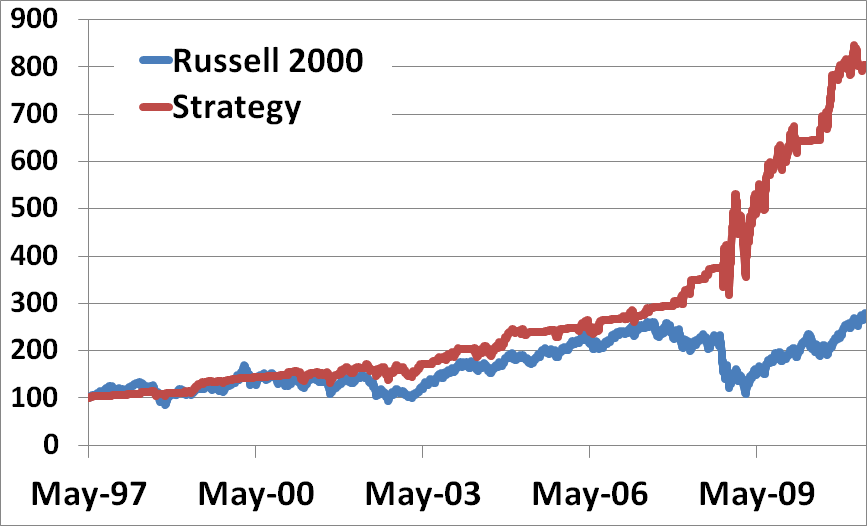

Stock returns for the subsequent 10 years show a strong correlation to where the P/E10 was in year one. In 1982, for example, an analysis of the historical stock-return data shows that the most likely annualized 10-year return for stocks would have been 15 percent after inflation.

The same analysis would have estimated that stocks purchased in the year 2000 would lose one percent per year after inflation.

What one stock allocation percentage makes sense both when the long-term return is likely going to be 15 percent real and when the long-term return is likely going to be a negative 1 percent real? There is none. Elect a Buy-and-Hold strategy and you insure that sooner or later you will be going with a stock allocation that is wildly wrong for you.

Many of today’s investors think of Buy-and-Hold as a neutral choice. The thought is I really am not sure of precisely how much I need to change my allocation, so perhaps I had better just stick with the neutral choice of leaving it where it is. No! The neutral choice is to remain at the same risk level at all times. Since the risk associated with stock investing is greater at times of high valuations, you must lower your stock allocation at such times to Stay the Course in a meaningful way. It is better to make the effort to change your allocation properly and get it a little wrong than to fail to make the effort and end up with a stock allocation wildly off the mark of what is proper for someone with your risk tolerance.

Part of the reason for the popularity of Buy-and-Hold is that many think of it as a safe choice. The apparent safety of this choice is illusory. You don’t want to be driving 65 miles per hour during a heavy snowfall. And you don’t want to be going with a 65 percent stock allocation when valuations are such that someone with your risk tolerance should not be going with a stock allocation of any more than 10 percent or 2o percent.

Buy-and-Hold does not diminish risk. It masks risks. That’s why I view Buy-and-Hold as the most dangerous investing strategy of them all.