Greed Is Good

Post on: 13 Май, 2015 No Comment

Wall Street bonuses are getting a bad rap, but they’re an important and useful part of the financial services industry. Taking them away could hamper the economic comeback.

Roy C. Smith

Updated Feb. 7, 2009 11:59 p.m. ET

(See Correction & Amplification below .)

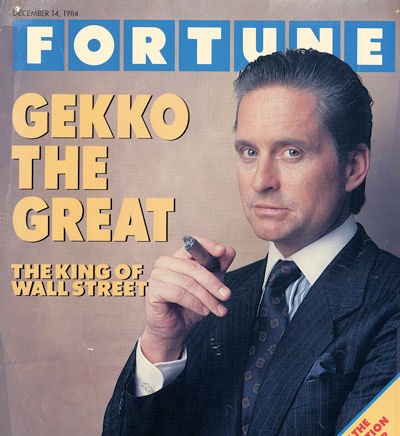

A look at Wall Street bonuses.

Many wondered if that was still the case last week, when New York State Comptroller Thomas DiNapoli released an estimate that the securities industry paid its New York City employees bonuses of $18 billion in 2008, leading to a public outcry. Lost in the denunciations were the powerful benefits of the bonus system, which helped make the U.S. the global leader in financial services for decades. Bonuses are an important and necessary part of the fast-moving, high-pressure industry, and its employees flourish with strong performance incentives.

The anger at Wall Street only grew at the news that Merrill Lynch, after reporting $15 billion of losses, had rushed to pay $4 billion in bonuses on the eve of its merger with Bank of America. Because Merrill Lynch and Bank of America were receiving substantial government funds to keep them afloat, the subject became part of the public business. The idea that the banks had paid out taxpayers’ funds in undeserved bonuses to employees, together with a leaked report of John Thain’s spending $1 million to redecorate his office, understandably provoked a blast of public outrage against Wall Street. The issue was so hot that President Barack Obama interrupted his duties to call the bonuses shameful and the height of irresponsibility. Then, on Wednesday, he announced a new set of rules for those seeking exceptional assistance from the Troubled Asset Relief Program in the future that would limit cash compensation to $500,000 and restrict severance pay and frills, perks and boondoggles.

ENLARGE

Lindsay Holmes

In the excitement some of the facts got mixed up. Mr. DiNapoli’s estimate included many firms that were not involved with the bailout, and only a few that were. Merrill’s actions were approved by its board early in December and consented to by Bank of America. But the basic point is that, despite the dreadful year that Wall Street experienced in 2008, some questionable bonuses were paid to already well-off employees, and that set off the outrage.

Many Americans believe that any bonuses for top executives paid by rescued banks would constitute excess compensation, a phrase used by Mr. Obama. But no Wall Street CEO taking federal money received a bonus in 2008, and the same was true for most of their senior colleagues. Not only did those responsible receive no bonuses, the value of the stock in their companies paid to them as part of prior-year bonuses dropped by 70% or more, leaving them, collectively, with billions of dollars of unrealized losses.

That’s pay for performance, isn’t it?

Wall Street has always been the quintessential, if ill-defined, symbol of American capitalism. In reality, Wall Street today includes many large banks, investment groups and other institutions, some not even located in the U.S. It has become a euphemism for the global capital markets industry — one in which the combined market value of all stocks and bonds outstanding in the world topped $140 trillion at the end of 2007. Well less than half of the value of this combined market value is represented by American securities, but American banks lead the world in its origination and distribution. Wall Street is one of America’s great export industries.

The market thrives on locating new opportunities, providing innovation and a willingness to take risks. It is also, regrettably, subject to what the economist John Maynard Keynes called animal spirits, the psychological factors that make markets irrational when going up or down. For example, America has enjoyed a bonus it didn’t deserve in its free-wheeling participation in the housing market, before it became a bubble. Despite great efforts by regulators to manage systemic risk, there have been market failures. The causes of the current market failure, which is the real object of the public anger, go well beyond the Wall Street compensation system — but compensation has been one of them.

ENLARGE

The industry became much more competitive when commercial banks were allowed into it. The competition tended to commoditize the basic fee businesses, and drove firms more deeply into trading. As improving technologies created great arrays of new instruments to be traded, the partnerships went public to gain access to larger funding sources, and to spread out the risks of the business. As they did so, each firm tried to maintain its partnership culture and compensation system as best it could, but it was difficult to do so.

In time there was significant erosion of the simple principles of the partnership days. Compensation for top managers followed the trend into excess set by other public companies. Competition for talent made recruitment and retention more difficult and thus tilted negotiating power further in favor of stars. Henry Paulson, when he was CEO of Goldman Sachs, once remarked that Wall Street was like other businesses, where 80% of the profits were provided by 20% of the people, but the 20% changed a lot from year to year and market to market. You had to pay everyone well because you never knew what next year would bring, and because there was always someone trying to poach your best trained people, whom you didn’t want to lose even if they were not superstars. Consequently, bonuses in general became more automatic and less tied to superior performance. Compensation became the industry’s largest expense, accounting for about 50% of net revenues. Warren Buffett, when he was an investor in Salomon Brothers in the late 1980s, once noted that he wasn’t sure why anyone wanted to be an investor in a business where management took out half the revenues before shareholders got anything. But he recently invested $5 billion in Goldman Sachs, so he must have gotten over the problem.

As firms became part of large, conglomerate financial institutions, the sense of being a part of a special cohort of similarly acculturated colleagues was lost, and the performance of shares and options in giant multi-line holding companies rarely correlated with an individual’s idea of his own performance over time. Nevertheless, the system as a whole worked reasonably well for years in providing rewards for success and penalties for failures, and still works even in difficult markets such as this one.

At junior levels, bonuses tend to be based on how well the individual is seen to be developing. As employees progress, their compensation is based less on individual performance and more on their role as a manager or team leader. For all professional employees the annual bonus represents a very large amount of the person’s take-home pay. At the middle levels, bonuses are set after firm-wide, interdepartmental negotiation sessions that attempt to allocate the firm’s compensation pool based on a combination of performance and potential.

At most firms, much or most of the bonus is paid in stock, which vests over several years, to reward long-term performance. But the market for talent is competitive and many firms have been compelled to offer guaranteed or minimum bonuses to recruit people, and some star traders have been able to negotiate specific profit-sharing arrangements regardless of what happens to firm-wide profits.

Most of the Wall Street bonuses paid in 2008 were largely directed to those with contracts providing for guaranteed minimums, to those whose efforts during the year contributed to making things better rather than worse, and to middle- and junior-level employees that the firms wanted to retain during difficult times. Last week, reports revealed that UBS, a Swiss bank, hired over 200 experienced brokers in the U.S. in the fourth quarter by offering some super-sized bonuses. Even in tough markets, poaching of valuable employees still occurs.

At the senior-most level, in which executives are major shareholders of their firms, all of Wall Street has suffered. The CEOs of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers each lost several hundred million dollars as their firms disintegrated. The shares of once-mighty Citigroup, AIG and Bank of America are all now below $6.50 per share. Many top Wall Street executives, including seven CEOs in the U.S. and several more in Europe, have been sacked. Not many other industries have such a harsh, up-or-down compensation system that is so closely tied to performance. The system, of course, is controlled by the firms’ boards of directors and approved by their stockholders. If investors don’t like it they can vote against it or sell their stock.

The entrance of federal funds into the industry, however, has changed things dramatically. For those firms taking TARP money (including some that didn’t really want it, and didn’t really need it, but had their arms twisted by the Treasury), it is clear that nothing resembling an excess of anything will be permitted. No large cash bonuses, no fancy airplanes or splashy office redecorations.

This is fair enough. Shareholders may be bamboozled into letting these things happen, but taxpayers shouldn’t be. Executive compensation paid in stock, especially in difficult times when stock prices are low, offers a strong incentive to turn things around. But the firms will need to be able to run themselves as competitive businesses, offering what it takes to get the best people and teams in place to do what has to be done to return to profitability. Neither the TARP nor Congress should get in the way of doing this. If they do, the most important employees of the firms they are trying to save will seek better situations elsewhere. These businesses are nothing more than their people.

Much of the work on Wall Street is done under great pressure to produce results over short time periods in rapidly changing environments while complying with a myriad of rules and regulationsit isn’t for everybody, regardless of brains, personality or motivation. Further, the hierarchy of Wall Street is very flat; people move up quickly based on their ability to seize or create opportunities; everyone wants to be judged on their performance and to be free to rise as far and as fast as they can. Firms made up of such characters generate a lot of energy and initiative, but they also need a lot of supervision and leadership. All are important to the firms’ ability to succeed from year to year, especially as markets change. Losing key players can be a serious jolt, and despite bear markets there is always another firm willing to hire away the best.

But the Wall Street bonus system has some serious flaws.

The most important is the amount of moral hazard that the system creates. Great rewards to executives are paid for successful risk-taking, but the penalties for unsuccessful risk-taking end up being borne by taxpayers. One remedy for this is to charge traders a cost for the capital they use based on the risk that they intend to put it into. Many firms just charge the firm’s own cost of the capital, and therefore overstate the profits they record on the riskiest trades. This also overstates the bonuses that should be paid on them.

Another broadly necessary remedy is to subject the entire industry to effective systemic risk regulation, something now being considered by Congress and the administration. They may decide to charge those firms thought to be too big to fail with an insurance premium for taking risks that could affect the whole financial system, similar to the premiums that banks now pay for deposit insurance. Alternatively, a powerful new regulator might be created to be sure that such large banks do not create more systemic risk than they should, by reducing the permissible amount of leverage that banks may use, for instance.

The short-term orientation of the compensation system is another flaw. This needs to be fixed by increasing the proportion of bonuses that reflect performance over a longer term, and to provide for clawbacks of bonuses accrued when positions or transactions go awry at a later time. Many firms have begun to do this.

Those who criticize Wall Street for excessive compensation may have less to worry about in the future. A recent study by New York University’s Thomas Philippon and the University of Virginia’s Ariell Reshef of compensation in the U.S. financial services sector since 1909 demonstrates that financial jobs were relatively skill-intensive, complex and highly paid relative to other industries until 1930, and became so again only after 1980, with wages peaking in 1930 and again between 1995 and 2006. They linked the high compensation periods to deregulation, high demand for corporate financial services and increased exposure to credit riskor in short, to periods of high innovation, bullish markets and extensive trading and risk-taking.

The current financial crisis is very likely to end with new sets of rules that will make it difficult for large banks to continue to operate as if they were hedge funds, by generating systemic risk through large trading positions in active markets. This will result in a change that should moderate bonuses paid by such banks, which they might have to make up for by increasing salaries. It may also encourage a migration of the best and brightest to smaller, less intensely regulated firms such as boutique investment banks, hedge funds or private equity managers.

Finally, the controversy over bonuses should remind everyone that a system of free-market capitalism operating inside a vibrant democracy can only succeed if the people accept its benefits and are not offended by what they may perceive (rightly or not) as abusive, greedy or in-your-face behavior. We are less than 10 years away from the last time there was public rage against Wall Street, and to the extent that excessive compensation is part of the problem, the solution is simply to curtail it. But compensation may not be a problem on smaller business platforms that do not involve systemic risk. The larger, complex financial institutions that do involve systemic risk may have to be forced into breaking up into smaller units that don’t threaten the whole system.

Still, the people are telling us they’re mad as hell and are not going to take it any more. Public anger is hard to deny, but we shouldn’t let it weaken an important industry. Sensible restraints and market forces will cause the industry to reinvent itself. Just has it has done several times since 1973.

Roy C. Smith, a professor of finance at New York University’s Stern School of Business, is a former partner of Goldman Sachs.

Corrections & Amplifications

The S&P 500 index fell 17.5% in 1973. This article incorrectly says the index fell 50% that year.