Globalization and the Developing Countries The Inequality Risk

Post on: 1 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

Globalization and the Developing Countries:

The Inequality Risk

Remarks at Overseas Development Council Conference, Making Globalization Work,

International Trade Center, Washington, D.C. March 18, 1999

Nancy Birdsall

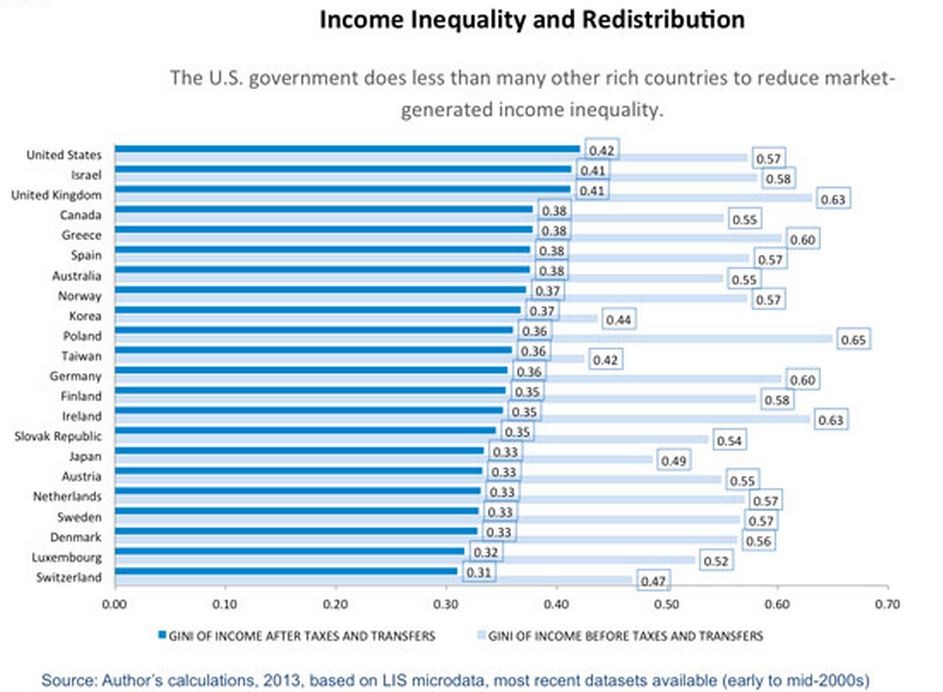

My task is to talk about globalization and inequality in developing countries, with emphasis on Latin America. I have a simple point to make: globalization puts developing countries at risk of increasing income inequality. The increase in inequality in the United States over the last 25 years (during which the income of the poorest 20 percent of households has fallen in real terms by about 15 percent) has been blamed, rightly or wrongly, on changes in trade, technology and migration patterns associated with increasing economic integration with other countries. For developing countries, any risk of increasing inequality associated with active participation in the global economy is even greater, if only because of the greater inherent institutional weaknesses associated with being poor. Latin America has a special disadvantage: its historical legacy of already high inequality. Inequality that is already high complicates the task of effective conflict management, which Dani Rodrik has just reminded us is a critical input to managing open economies. In the past, for example, high inequality combined with the politics of redistribution led to periodic bouts of populism in Latin America – ineffective and counterproductive efforts to manage the conflicts provoked by the dangerous combination of high inequality and hard times.

Let me start with two prefatory remarks. First, globalization – that is the trend of increasing integration of economies in terms not only of goods and services, but of ideas, information and technology – has tremendous potential benefits for developing countries. Nothing I say should suggest otherwise. The challenge is to realize the potential benefits without undertaking huge offsetting costs. Second, not all inequality is a bad thing Some inequality represents the healthy outcome of differences across individuals in ambition, motivation and willingness to work. This constructive inequality provides incentives for mobility and rewards high productivity. Some would say constructive inequality is the hallmark of the equal opportunity society the U.S. symbolizes. Increases in this constructive inequality may simply reflect faster growth in income for the rich than the poor – but with all sharing in some growth. But of course it can also be true that inequality is destructive. when for example it reflects deep and persistent differences across individuals or groups in access to the assets that generate income – including not only land (which is extremely unequally distributed in Latin America) but, most important in today’s global information age, the asset of education. Obviously this destructive inequality undermines economic growth and efficiency, by reducing the incentives for individuals to work, to save, to innovate and to invest. And it often results in the perception if not the reality of injustice and unfairness – with the political risk in the short term of a backlash against the market reforms and market institutions that in the long term are the critical ingredients of shared and sustainable growth.

I have three parts to my remarks: first, on inequality and market reforms; second, on inequality and the recent financial crisis; third, on what to do, or more grandly on policy implications.

On Inequality and Market Reform

Consider some examples of how the market reforms associated with globalization can affect inequality in developing countries.

First, trade liberalization. On the one hand, trade liberalization makes economies more competitive and thus is likely to reduce disequalizing rents to insiders. The end of import substitution programs and associated rationing of access to foreign exchange has probably been the greatest single factor in reducing the corrosive effects of corruption and rent-seeking in Latin America. Trade liberalization can also generate new labor-intensive jobs in agriculture and manufacturing – raising the incomes for example of the rural poor. And trade liberalization implies cheaper imports, reducing the real costs of consumption for the urban poor – who after all unlike the rich use most of their income for consumption.

On the other hand, recent evidence shows that trade liberalization leads to growing wage gaps between the educated and uneducated, not only in the OECD countries but in the developing countries. Between 1991 and 1995 wage gaps increased for six of seven countries of Latin America for which we have good wage data. The exception is Costa Rica, where education levels are relatively high. Apparently the combination of technology change with the globalization of markets is raising the demand for and the wage premium to skilled labor faster than the educational system is supplying skilled and trainable workers. In Latin America education levels have been increasing, but painfully slowly – with for example only 1.5 years of additional education added to the average education of the labor force in three decades (in contrast to twice that increase in Southeast Asia). And the distribution of education, though improving slowly, is still highly unequal, meaning that many of today’s workers have even less than the current average of about 4.8 years of completed schooling.

In short, the effect of trade liberalization on inequality depends – including on the extent to which a country’s comparative advantage lies in job-using agriculture or manufactured exports, and on the extent to which education has been increasing and is already broadly shared. In Costa Rica, with good education and a high proportion of the relatively poor engaged in smallholder coffee production, trade liberalization has had equalizing effects. But in Mexico, where the rural poor are concentrated in food production and education levels are still low and unequally shared, income declined between 1986 and 1996 for every decile of the income distribution except the richest, where it increased by 15 percent. Unfortunately Mexico is probably more typical than Costa Rica. For the region as a whole, though trade liberalization is likely to increase average incomes, it is also likely to increase inequality, at least in the near future, because education efforts have lagged and because the region’s comparative advantage (other than in Costa Rica and Uruguay) is in capital-intensive rather than job-creating natural resource-based production.

A second example is privatization. Privatization of utilities (power, water, telecommunications) has been good news for the lower deciles of the income distribution all over the developing world. Why? Because it has dramatically increased access to services. Prior to privatization, publicly managed utilities were chronically insolvent financially and thus their services were highly rationed. The rich had access to water to fill their swimming pools (and often at artificially low prices meant to protect to the poor!) while the poor paid 20 times the unit cost to purchase water from private trucks.

On the other hand, it is increasingly obvious that privatization poses grave risks of concentrating wealth unless done well and with the full complement of regulation. In small economies with limited competition and high concentrations of political and economic power, even privatization of firms that in larger settings with more arms-length and transparent market rules would face the discipline of competition, can end up locking in rather than eliminating private privileges. In a recent poll in Latin America, respondents agreed by three to one to the general statement that “a market is best”. But in Argentina, Peru, Colombia, Uruguay and Panama, fewer than half supported the idea that privatization had been beneficial – apparently because of the widespread perception that the high costs of newly privatized services reflect lack of real competition. Russia is of course the most extreme example of the danger that corruption will infect the privatization process. Those of you familiar with the saga of the privatization of banks in Mexico in the early 1990s, and the subsequent political fallout in 1998 (when a sound proposal from the technical point of view was nearly derailed by the political effects of the 1995 rescue of many insider bank owners and borrowers) will recognize the political risks associated with a privatization process that ends up reinforcing rather than diffusing initial inequality of wealth and privileges.

The risks of privatization arise because developing and transitional economies, almost by definition, are handicapped by relatively weak institutions, less well-established rules of transparency, and often, not only high concentrations of economic and political power but a high correlation between those two areas of power. These conditions combine to make it difficult indeed to manage the privatization process in a manner that is not disequalizing.

Third: financial liberalization. On the one hand, there is little doubt that low- and middle-income consumers and small and medium businesses were the biggest losers in the 1980s with the repressed banking systems of Latin America. Controls on interest rates reduced their access to any credit at all, and government-run credit allocation favored small enterprises only on paper. Similar arrangements almost surely penalized the middle class and the poor in Africa. In the medium term, elimination of financial repression and the increased competition of a modern and liberalized financial sector will increase access to credit for small enterprises and raise the return to the banking deposits which are the principal vehicle for small savers. The advantages for small business in turn is likely to generate more good jobs and raise wages for the working poor.

However in the short run at least, financial liberalization tends to help those most who already have assets, increasing the concentration of wealth which undergirds in the medium term a high concentration of income. For one thing, liberalization increases the potential returns to new and more risky instruments for those who can afford a diversified portfolio and therefore more risk, and who have access to information and the relatively lower transacting costs that education and well-informed colleagues provide. In Latin America, with repeated bouts of inflation and currency devaluations in the last several decades, the ability of those with more financial assets to move them abroad (often while accumulating corporate and bank debt that has been socialized and thus eventually repaid by taxpayers) has been particularly disequalizing. In Mexico between 1986 and 1996 small savers who kept their assets in bank savings accounts lost about 50 percent, while those able to invest in equity instruments realized modest gains. Those who moved their assets into dollars or dollar-indexed instruments before the 1994-95 devaluation did best of all in terms of local purchasing power.

On Inequality and the Financial Crisis

The recent financial crisis has highlighted how volatility associated with global capital markets can compound the problem of destructive inequality in developing countries. For example, high inflows of capital generate inflationary pressure and hurt labor-intensive agriculture and manufactured exports, especially but not only under fixed exchange rate regimes. In Asia and Latin America, Gini coefficients of inequality increased during the boom years of high capital inflows in the mid-1990s, as portfolio inflows and high bank lending fueled demand for short-term inelastic assets such as land and stocks, favoring the rich. In both regions the poor gained less during the boom, and then lost more with the bust. During the bust, with capital fleeing, the high interest rates countries are forced to impose to protect their currencies (again, whether the exchange rate is fixed or floating), hurt small capital-starved enterprises and their low-wage employees most, and of course reduce employment in general. In Latin America, a high-interest environment also tends to benefit net savers and hurt small debtors, with a regressive impact; this has certainly been the effect in Mexico and Brazil. Helmut Reisen has recently pointed out the additional regressive impact of the fiscal cost of bank bailouts in developing countries, simply because the redistributive impact of public debt tends to be negative. He recalls Keynes’ Tract on Monetary Reform, where Keynes reminds us that public debt implies a transfer from taxpayers to rentiers. Worst of all in Latin America’s historically inflation-plagued economies (though this is notably much less the case the today), the poor hold cash, the non-interest bearing part of the debt which has been subject to considerable inflation tax.

The problem emerging markets face is a broader one. Because global market players doubt their commitment to fiscal rectitude at the time of any shock, they are forced into tight fiscal and monetary policy, to re-establish market confidence, at precisely the moment when in the face of recession they would ideally implement counter-cyclical fiscal and monetary measures in order to stimulate their economies. The austerity policies that the global capital market demands of emerging markets are precisely the opposite of what the OECD economies can afford to implement – such relatively automatic Keynesian stabilizers as unemployment insurance, increased availability of food stamps, and public works employment programs, the ingredients of a modern and effective social safety net. Furthermore we know now that the effects of unemployment and bankruptcy on the poorer half of the population can be permanent; in Mexico increases in child labor force participation and reduced enrollment in school during the 1995 downturn have not been reversed. Similarly a collapse in employment opportunities for labor force entrants can have lifetime effects on job possibility and income-earning potential for the affected cohorts.

On What to Do: Are There Policy Implications?

There are implications for domestic policy, and for international economic policy as well.

On the domestic policy side, one obvious implication of the vulnerability of emerging market economies to volatility in global capital availability is to reduce reliance on foreign capital. Dani Rodrik emphasizes the centrality of a locally financed investment push to the success of small open developing economies, implying the need to increase private and/or public savings. The recent crisis highlights, for a different reason, the importance of public savings. If public spending in developing countries is to play a socially and economically efficient countercyclical role during a downturn, public savings in the form of a prior and precautionary fiscal surplus has to have already created the necessary fiscal space to finance safety net programs. Today Brazil has virtually no such fiscal flexibility, and is paying a price in increasing inequality. Chile does have space, and any increase in inequality will be lower. Of course, maintaining and insulating politically a fiscal surplus is no easy task – as the current politics-of- the-surplus debate in the U.S. shows.

In addition, the developing countries face the same problem as the OECD countries: raising revenue to finance a social safety net requires taxing the public. In a global economy, there is some evidence that it is increasingly difficult to tax footloose capital (and even to tax the income of highly educated and internationally mobile labor). David Hale noted this morning that Singapore and South Africa have recently reduced corporate taxes. So countries ironically need to tax most in good times those who are most vulnerable in bad times – and to the extent these are the innocent bystanders to the excesses of the boom and bust cycles, the impression if not the reality of unfair burden sharing is heightened.

Assured revenue for an effective safety net minimizes the welfare and human capital losses the poor otherwise suffer with economic or other shocks. But in the medium run, the best vaccine against inequality is widespread access to good education. In today’s global information age, education is the people’s asset; the more there is of it, the lower the inequality of real total wealth in the long run. It is still unfortunately the case that in many countries of Latin America, education is a vehicle for reinforcing rather than compensating for initial differences across households in income and wealth. I have written and spoken elsewhere about the need for aggressively targeted public programs to bring good education to the poor. Unfortunately in a vicious circle, education for the poor is a political and technical task made all the more difficult where high current income inequality, as in Latin America, constrains effective demand of poor households and generates resistance of rich households to use of the public fisc to finance effective basic schooling.

A third key ingredient of domestic policy to counter inequality is what might be called an aggressive EOF bias, i.e. constant and vigorous Equal-Opportunity Fine-tuning of economic policies. For example, if macroeconomic equilibrium requires high interest rates, temporary measures to ensure equal access to credit for small and micro enterprises may be warranted. If a major restructuring of the financial sector is required, distributional considerations demand that bank shareholders assume their share of losses; not all the costs should be passed to depositors and taxpayers. Privatization schemes can make special provisions under which small investors can buy small lots of shares, and can borrow at reasonable rates to purchase available shares – as has been tried in Peru; or can be arranged to generate widely distributed benefits for all citizens in the form of future pension assets, as in Bolivia.

What about international economic programs and policies? First, the international financial institutions could pay much more attention to the political reality of inequality of assets and income in developing countries. Conditionality associated with international lending and grants could be much more explicitly focussed on slashing subsidies that benefit the rich, on encouraging and financing market-consistent land reform, and most important, on ensuring that there is effective public education, on which the poor so heavily depend if they are to join in the benefits of a market economy.

Second, the OECD countries could revisit their trade stance as it affects the poor in developing countries. Protection of agriculture and of textiles discriminates against the poor within countries. The head of the World Trade Organization has proposed elimination of tariffs on all imports of the world’s 50 poorest countries. This would reduce income inequality not only across but within poor countries.

Third, the poor and vulnerable in developing countries might well benefit from some international financing of countercyclical safety net programs in emerging market economies that are hit by global liquidity crises. Max Corden has set out the conditions that would make such financing appropriate, which include a solid record of sound fiscal policy in recipient countries; the political capacity to mount such programs without corruption and to unwind them when the crisis recedes; and the long-run fiscal capacity to service any resultant external debt. These are stringent conditions, but the fact is that Mexico in 1995 and Korea in 1998 could have qualified, and could thus have reduced the tremendous and terrible costs to human welfare and the permanent losses of human capital associated with the impact of financial crises on those Joe Stiglitz has called the innocent bystanders. International financing is now used during liquidity crises to build reserves (and thus market confidence) and to finance imports. Why do we know so little about the potential costs (e.g. effects on inflation) and benefits of external financing earmarked for temporary increases in spending on social insurance and safety net programs?

* * * * * * *

In conclusion, the developing countries face special risks that globalization and the market reforms that reflect and reinforce their integration into the global economy, will exacerbate inequality, at least in the short run, and raise the political costs of inequality and the social tensions associated with it. The risks are likely to be greatest in the next decade or so, as they undergo the difficult transition to more competitive, transparent and rule-based economic systems with more widespread access to the assets, especially education, which ensure equal access to market opportunities. During that transition, more emphasis on minimizing and managing inequality, on making the market game as nearly as possible a fair one, even in the short run, would minimize the real risks of a protectionist and populist backlash. A backlash would be a shame, as in a perverse twist, it would undermine the benefits that more open and more globally integrated economies and polities can deliver to all the people of the developing world.