Global Asset Allocation

Post on: 23 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Is Global Asset Allocation Still Appropriate?

by Frank Armstrong

Last year brought globally diversified investors solid but uninspiring results. For the third year in a row, global asset allocation under-performed a domestic-only portfolio. So, it’s important to examine once again the rationale for international investing. After all, an appropriate investment strategy should be driven by more than just perverse stubbornness. I hope that you will conclude that it is still an appropriate model for prudent investment of your hard-earned dollars.

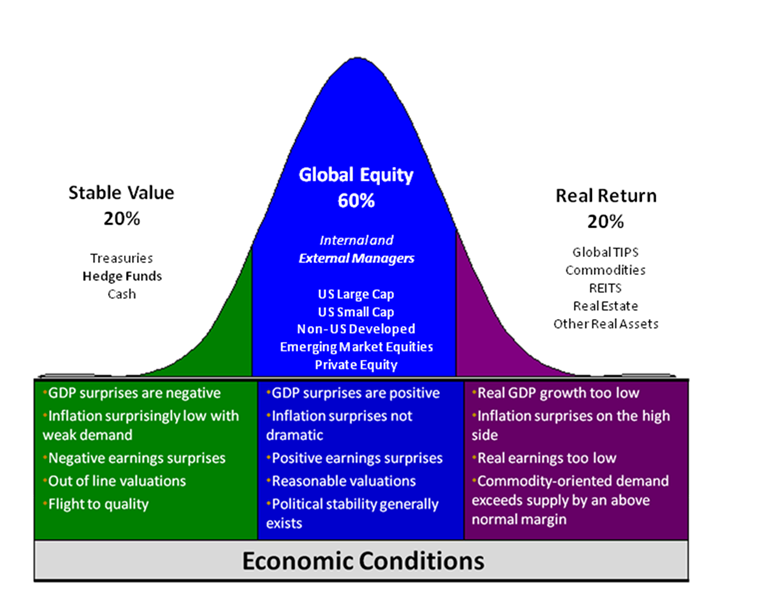

The objective of global diversification is to produce liberal returns over time while taking the very minimum possible risk to generate them. A rational investor should be obsessed with producing satisfactory returns with minimum cost, minimum risk techniques.

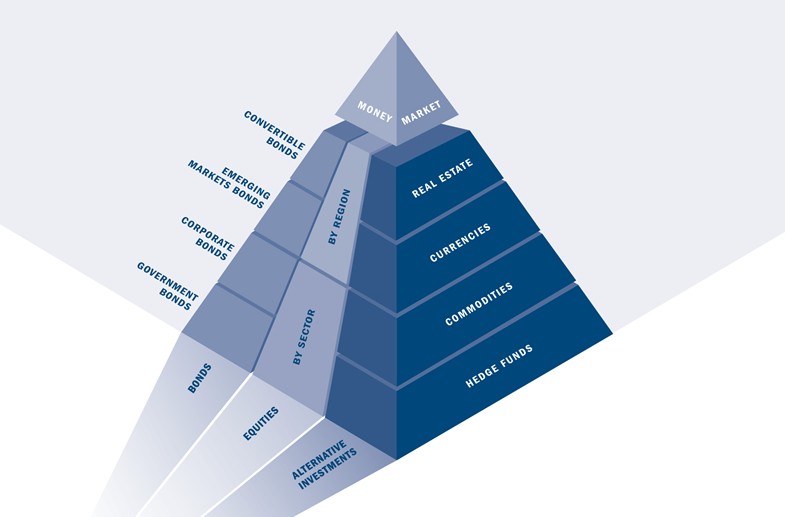

The overall strategy is really very simple. It consists of two parts: a bond strategy and an equity strategy.

The bond strategy is designed to provide either a store of value to fund known future disbursements, or to reduce portfolio risk to a tolerable level for risk averse investors. A short-term, domestic-only, high quality bond funds should generate a liberal positive return with minimum risk.

The equity strategy divides the world’s stock markets into nine broad asset classes, four domestic and five international. Over a long period of time, eight of the asset classes have outperformed the S&P 500, while the ninth is the S&P 500! Some of the asset classes have outperformed the S&P 500 by more than 10% average compounded per year. As you can imagine, these asset classes carry additional risk. Yet, when we mix these asset classes together, because they have low correlations to one another, the resulting risk at the portfolio level is not substantially higher than the S&P 500. There is strong economic reason to believe that these asset classes will continue to generate excess returns, and there is no evidence to support the conclusion that correlations are increasing.

Each asset class has had periods of under and over performance. That’s what low correlation means. There is a distinct pattern to this performance. Small companies have higher performance than large. Note the high number of five-year periods where the top performing asset class was international small during the period 1970 to 1996. Domestic small companies usually perform better when domestic large companies outperform foreign, and the reverse is also true. When foreign large companies outperform ours, the foreign small companies usually have even better relative performance. There is every reason to believe that this pattern will continue.

The conclusion is unmistakable: diversification through inclusion of foreign categories in an investment portfolio reduces risk and increases rates of return. However, diversification has a cost. Sometimes it works when we wish it wouldn’t. While diversified portfolios have generated strong absolute total returns, they can never be favorably compared to the strongest single asset class of a particular time period. By definition, a diversified portfolio will never have all its assets in the best performing asset class. Furthermore, if there are losers anywhere in the world, a diversified portfolio will hold them also. We can accept that if we believe that the total value of the world’s economy will continue to grow. For a capitalist looking at the world since the fall of feudalism, that shouldn’t take a great leap of faith. We have made a decision to diversify away the opportunity to have short-term stellar performance in favor of more consistent long-term performance. It’s the classic turtle and hare story.

Perhaps the greatest risk that diversified portfolios face is psychological: the tendency of investors to look back and compare performance to the best asset class available. It is natural for US investors to focus in on the S&P 500, except of course, when it’s not doing well. When it’s doing great, there is a tendency to believe that it’s the only relevant standard. Everyone that isn’t matching that standard feels like a nerd.

Every investor has (or should have) a bias, and a philosophy that guides his policy and strategy. Our bias is for global diversification, small companies, and a very strong value tilt. Our model is over-weighted in the United States, small companies, emerging markets, and value. Extensive research documents that these segments of the world’s economies will produce the highest rates of return, and that the mix will not generate excessive risk.

Whether you are a fighter pilot, brain surgeon, basketball player or investor, you will be looking for the high probability shot, the strategy designed to generate the highest probability of a successful outcome. By dividing the world into nine different equity asset classes, we are taking small bets on each rather than shoot the whole works on any particular market. This is a fundamental risk control technique.

It is our expectation that over long periods of time, this equity portfolio will deliver at least 3 1/2 percent additional rate of return over the S&P 500. However averages are funny things. If you were to put one hand on a block of dry ice and the other on your stove, a statistician might observe that on average you are comfortable. We know that’s not true. Average rates of return obscure long periods of both under-performance and over-performance relative to the long term trend. Nothing about our strategy implies that we will outperform anything by any amount each and every year. Indeed, we expect periods of time when we will under-perform a domestic only strategy. These periods of time may be lengthy. We must accept that if we have confidence that the long-term strategy is sound.

The domestic large company market has just domestic markets scored their best three- year period in history, with the S&P 500 averaging 31.2% per year. The S&P 500 annualized return for the three year period ending September 30, 1997 was more than double the return of the previous 10, 25 and 50 years! This astounding result could not have been predicted, and is outside of the expectations of our model. No fiduciary would ever have dared place all his chips on that one number.

The extended run up left the US market one of the highest priced in the world. Valuations are almost twice as high as many other developed markets. Looking forward, we would be poorly advised to bet the farm on a continuation of such an abnormal event.

The situation with small companies is very similar. Only the Netherlands even comes close to our valuations.

With the benefit of perfect hindsight, every foreign market looks like trash in comparison. Foreign stocks have caused us to greatly under-perform a domestic-only strategy for three straight years. Should we dump them’ If so, the same logic would have compelled us to dump domestic stocks in 1974 after a very bad two-year decline, and again in 1989 when Japan looked invincible. Of course, we would have missed some of the great opportunities of our century, and our returns looking back would have been pretty dismal.

The decision to fire an asset class is considerably different than firing a manager that under-performs his assigned asset class. Lipper recently reported that of the actively managed diversified domestic mutual funds, only 6%, or one manager in 16, managed to match the three-year performance of the S&P 500. Even worse, the average under-performance exceeded 7% per year! Clearly many of those managers ought to be replaced, in our opinion with index funds.

However, short-term under-performance is not a reason to fire an asset class. An investor would have to be convinced that the asset class had no future prospects, and that the economic reasons for its inclusion had irrevocably changed. Asset classes always recover. Short of a global nuclear exchange we see no reason to believe that they shouldn’t.

Index funds have faithfully mirrored the performance of the selected asset classes. All of the classes have performed within the expectations of the model we constructed. The absolute returns have fallen well within our expectations, and nothing would indicate that the model is flawed in any meaningful manner.

The decision to abandon Strategic Global Asset Allocation should only be made if the investor is certain that he can consistently time the world’s markets. There is no evidence that any investor has been able to meet that test. There is no reason to believe that any ever will.

The current economic problems in Asia are certainly unpleasant. The effects on our markets and economy have not been trivial. The Asian assumption that a locally brewed combination of cronyism, capitalism, and centrally guided economies are somehow superior to market driven economics has been strongly refuted. The stock markets have responded accordingly. However, the end of the world as we know it is not near! We have seen similar problems in this country 15 years ago, and more recently in Latin America. While Chicken Little may issue dire predictions, a more likely outcome is that the recent turbulence will accelerate adoption of long overdue fundamental reforms in Asia.

We note with some concern that a number of observers have recently opined that it is not necessary for American investors to diversify their portfolios into foreign markets. These observations are total rubbish, and supported with not one single fact. While everyone is entitled to an opinion, The Wall Street Journal amongst others ought to be ashamed of dignifying such drivel with publication.

History, economic theory and common sense show us that no single country or region will dominate the world indefinitely. We all know that risky asset classes will produce higher total returns over time than safe asset classes. We should accept that markets cannot work if they only go straight up. Corrections are a built in part of the capital markets. The timing of these corrections cannot be known in advance. The extent of these corrections is directly related to the return of the asset class. The world would be a very strange place indeed if that wasn’t the case. The world’s economic system would have no way to effectively ration capital.

I should note that what looks like a disappointing result to an American investor over the last three years, looks like a glorious result to a Japanese investor; and a few years ago they could have exchanged places. But, had each held a diversified portfolio over the entire period, they would both be pretty happy campers today.

I have no wish to sugarcoat the recent relative performance for global investors. However, I do think that we must put it into the perspective of our long-term objectives. Global asset allocation strategies have generated strong absolute total returns at minimum risk levels. The recent relative performance is no reason to jump ship. My conclusion is that until we have a failsafe crystal ball foreign diversification is prudent, effective, and appropriate. The proper action is to maintain course.

Questions

- The author makes an argument for wider diversification into a number of different asset classses. What is the basis for the argument?

- Will this diversified portfolio do better than a portfolio composed entirely of one asset class? Why or why not?

- Should this decision on diversification be affected by the recent performance of each asset class? Why or why not?