G20 Okun s Law economic growth and job creation (maybe)

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Meta

G20: Okuns Law, economic growth and job creation (maybe)

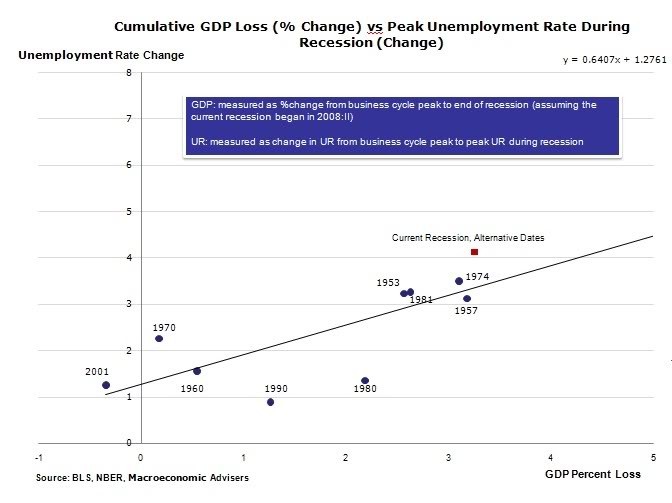

As I head off to Day 1 of the G20 it is probably worth noting that the big ticket item on the agenda will be a proposal to increase global GDP by 2%, which in turn will lead to an increase in jobs. Items that wont be discussed today and tomorrow (apart from climate change) will be the required re-engineering of Okuns Law which looks at the statistical linkages between economic development and job growth. Since Arthur Okun first designed the modelling the rate of return on jobs to GDP has been in decline (and he died long enough ago to not incorporate the rise of contingent staffing in his theories). Here are two stories that look at the rise in economic growth and how it is not necessarily translating into job creation.

Via G20Watch. Will growth mean more jobs? Excerpt (but click through to read the entire story and check out the site, its an excellent resource):

The recent uptick in the US economy has sent positive vibes around the world, signaling perhaps that global sluggishness is on its way out. Yet the positive jobs numbers accompanying that growth belie a reality that is far more grim than realised. Much of the increase in employment has been in the low-wage services sector, mainly retail business, suggesting an economic softness that almost seems like quicksand.

The G20 leaders are bent on raising the global economic growth rate to 2% or more than current projections. The economic logic behind this mysterious number is an unspecified investment commitment and reforms that collectively would induce economic growth and get the world economy moving again. The question is, will it get the economy moving again in terms of jobs? In fact, there is no explicit discussion by the G20 on the employment challenges that confront the world economy.

The presumption is that growth means employment. That might used to have been true, but it is less so these days because of globalisation. The adage, ‘what’s good for General Motors is good for America’ is not necessarily true anymore, since investment in China may not employ American workers, but would fatten shareholder earnings. Of course, Chinese workers could buy more American products, but witness the US trade balance with China—it has persistently been negative. And as the recent growth improvement suggests, growth does not ensure quality jobs.

The twenty largest economies do have global clout, but that influence comes in many shades, with different levels of economic standing. However, all of them suffer, albeit differently, from not having enough quality jobs. It is not an exaggeration to say that labor markets in the neo-liberal era have changed substantially. Good paying, permanent jobs with decent benefits are fewer in an era of contract, temporary, and part-time jobs. This is the case for most OECD countries. Even Japan, home to lifetime employment, suffers from an increasing number of people not-in-employment-education-training (NEETO). South Korea, successful in creating plenty of labor-using jobs during the heyday of export industrialisation, is now faced with a slow-growing economy and increasing share of contract and temporary workers.

Another story, from earlier in the year via Fortune (hardly a left-wing think tank) also reported on the phenomenon. Why stronger GDP growth isnt creating more jobs. Excerpt:

GDP growth is rising.

Immediately after a recession, strong GDP growth doesn’t tend to produce the same level of job growth as usual. That’s because GDP at that moment is rebounding rather than growing. What’s more, employers are slow to hire after a recession. That’s what happened in 2010 and 2011. But we are now four years out of the most recent recession, so it’s odd that the relationship hasn’t returned to normal.

Hours and productivity can mess with the GDP-to-jobs equation. As hours and productivity go up, employers can make more money with the same number, or fewer, workers. But the average work week has not grown much recently and productivity, after growing rapidly in the 1990s and then right after the recession, has been flat-lining as well.

Most of the economists I talked to shrugged it off. It’s mostly a short-term problem, they said. Most people think December’s jobs number represented a temporary slowdown, perhaps caused by the cold weather. Job growth will rebound in January, they say. If that happens, the GDP-to-jobs number will look more normal. For all of 2013, the ratio of jobs to GDP growth was 88,000. So we’re not that far off the 115,000 average when you look at the whole year, even if recently the number has been more like 50,000.

But I don’t think you can completely write off this trend. Yes, December’s jobs number was perhaps worse than it should have been, and it may very well be revised up. But it will not be revised to a figure like 300,000, even after adjusting for the weather. The fact of the matter is the job market is still slow. And at least part of this has to do with the fact that the mechanism we have used to turn economic growth into jobs is not working as well as it used to.

The lack of lending by the big banks may very well be one contributing factor. Another theory: Companies have gotten greater rates of return investing in capital in the past decade or so than they have in putting the money into hiring more workers. That’s led companies to believe that the best use of their money is to plow it into technology or buying back their own stock. But, as recent productivity numbers show, the benefits from those investments are falling. Corporations don’t seem to have noticed that yet.