EuroDollar Parity Is Now the New Economic Normal

Post on: 1 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Exclusive FREE Report: Jim Cramer’s Best Stocks for 2015.

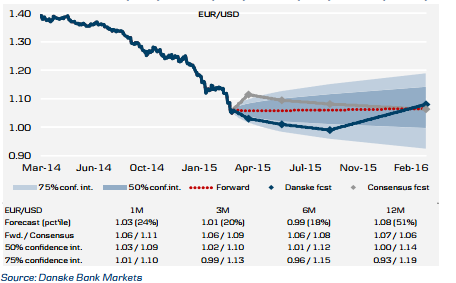

NEW YORK (Real Money ) — The euro has been falling through support after support lately, threatening to hit parity with the dollar. And why not? The dollar was stronger than the single European currency all those years ago right after the euro was launched, and there really is no reason why it shouldn’t be stronger than the euro now.

In economic terms, the U.S. is a stronger economy. It is bigger in absolute terms than the eurozone, too — GDP in the euro area was $12.7 trillion in 2013 vs. $16.7 trillion in the U.S. — and it has been recovering much quicker from the financial crisis that started in 2007.

If the Federal Reserve starts raising interest rates in the summer, as more and more analysts expect it to do, it will be the best proof that the U.S. has left that crisis behind. The weak dollar has had a lot to do with the recovery — by printing money, the Fed has helped the U.S. government issue more debt and therefore put more money in the economy. It has also boosted exports.

But besides the easy monetary policy and the lax fiscal one, the U.S. has had other advantages that played an important part in its recovery and that are impossible to replicate in the eurozone. Just a few examples: a flexible labor force, with easier hiring and firing of workers (consequently, it is much easier for people to jump from one job to the next), fiscal union with a federal budget, and a common language, which means workers can move easily from state to state searching from work.

Apart from these structural differences, there are differences in business environment as well, with much less red tape and regulation clogging business processes in the U.S. and a go-getter mentality that is sometimes missing from Europe’s largest economies. This mentality has encouraged investing in shares in the U.S. where retail investors help allocate capital efficiently and therefore help the economy move on. In the eurozone, by contrast, savers usually prefer passive savings accounts to shares, so stock markets are usually much smaller, sleepier places.

There are indeed some green shoots in Europe, with macroeconomic data such as investors’ confidence, PMIs, unemployment and retail sales improving everywhere, even in the periphery countries. However, much of this has to do with the effects of a weaker euro, rather than with a fundamental strengthening of the eurozone’s economy. RBS’s strategist Alberto Gallo has illustrated the link between the weaker euro and the economic surprise index for Europe as calculated by Citigroup in a chart: