ETFs v Mutual Funds

Post on: 1 Сентябрь, 2015 No Comment

ETF Cons

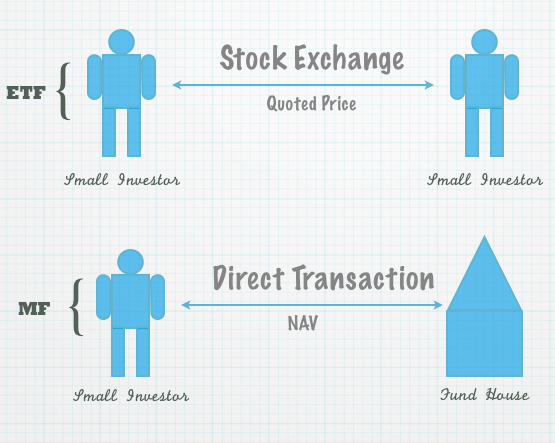

When you buy or sell an ETF, you must buy/sell it on the open market, like a stock. When doing so, you must specify an order type (e.g. market, limit, etc.) and an execution price (if it’s not a market order).

If you enter a market order, particularly for large orders, you may get quite poor execution prices, suggesting a large implicit (i.e. effective) transaction fee.

If you enter a limit order, the price you enter may not get you execution in the near future, perhaps causing you to have to re-price your order to a less desirable price in order to increase the chances of getting execution in the near-future. This tends to cause increased cash drag and another potentially large implicit transaction fee.

In our opinion, this may be the biggest con to consider for ETFs. It is both dramatically simpler, and often less costly, to buy a similar no-load open-end index fund.

When you buy or sell an ETF, you implicitly pay (as a hidden fee) one-half of the ETF’s bid-ask spread. Bid-ask spread is the difference in price between the market price for buying the ETF and the market price for selling the ETF at any point in time. Note that, for a conventional no-load mutual fund, there is no bid-ask spread involved.

An ETF’s bid-ask spread can be quite small (e.g. for domestic large-cap stock ETFs) or quite large (e.g. for new and thinly-traded ETFs).

ETFs may not be as tax efficient as you’d like. At present, qualifying dividend distributions from stocks are taxed at a preferentially low tax rate in the United States. One of the requirements to qualify for this low rate is that the stock has been held for at least 60 days. Due to share creation activity, this standard may not be met all the time. Thus, a portion of the dividend income received (and distributed) by the ETF may not qualify for the preferentially low tax rate for qualifying dividends.

Conventional index mutual funds have more control over this than do ETFs, and are therefore more likely to have a higher percentage of their distributed dividends qualify for the preferentially low tax rate.

ETFs won’t track indexes as well as conventional index mutual funds. A mutual fund’s share price is always, by definition, the fund’s net asset value (NAV). The NAV is just the weighted-average current market value of all the fund’s holdings, expressed on a per-share basis.

An ETF, on the other hand, is valued by the market. So even if its holdings are EXACTLY consistent with those of the index, its market price at any particular time can be either above or below the NAV (meaning it can be sold at either a higher or lower price than the per-share value of its underlying securities).

The difference between NAV and market price for an ETF won’t ever be very high because institutional arbitrageurs are able to either create or redeem shares of the ETF using the underlying stocks. This tends to drive the ETF price back towards its NAV. However, this tracking error is likely to be higher for ETFs which hold less liquid securities (e.g. emerging markets stocks).

There are relatively few bond ETF options available at present. However, note that ETFs are less desirable for bonds anyway — since a relatively small portion of a bond’s total return is due to capital gains, the tax efficiency benefit of bond ETFs is relatively trivial.

If the ETF is organized as a Unit Investment Trust (e.g. the original SPDR ETF), then all dividends the fund receives are required to be held in a non-interest bearing account until distributed to investors. This causes a cash-drag on the fund’s earnings which conventional index mutual funds (and non-UIT ETFs) don’t experience.

On the other hand, ETFs generally don’t have this as an alternative. They pay out distributions as cash. If you want to then reinvest that cash, you need to take some action to do so (and incur whatever transaction costs apply).