Does Market Timing Actually Work

Post on: 27 Август, 2016 No Comment

Why not just buy low and sell high? That’s easy enough, right? The classical answer is a resounding no and there are reams of analyses to prove that it’s not a good idea to try to do this. Most arguments against timing make the case that the market is extremely volatile and impossible to predict. It’s extremely easy to miss the best performing days and if you do you will have substantially worse performance than if you had stayed in the market the entire time. I’ve seen many variations of the following analysis [1] over the years:

The bottom line of this analysis is that unless you have a crystal ball you are going to miss major upward market moves and you will seriously undermine your returns. In fact, in 1975 William Sharpe published a seminal article on this topic: “Likely Gains from Market Timing”. In this article Sharpe demonstrated statistically that in order to benefit from a market timing strategy you had to guess right 74% of the time. [2]

Historic performance data confirms this conclusion. When Brinson, Hood, and Beebower conducted their analysis of the performance of 91 pension plans from 1974 to 1983 they determined that market timing had detracted from performance by .66% [3]

So maybe we should just end the article here. Why go on? Maybe because everyone believes that they are above average and people don’t like the idea of a passive strategy. Thankfully, there are better reasons.

First, every anti-timing analysis that I have seen, such as the first example given, focuses on the performance of binary strategies – you switch from being 100% in the market to being 100% out of the market. A more prudent strategy, and one that is actually practiced by portfolio managers, involves moderately adjusting your market exposure depending upon some appropriate signal. However, I have not seen this examined in the research.

Secondly, bubbles do occur and after the fact everyone clearly sees how overvalued the bubble assets were. There are historic patterns and there are limits to what is a reasonable price for any asset. If we can learn to leverage this knowledge then perhaps we can boost our returns.

I skimmed through parts of Graham (In case you didn’t know, Benjamin Graham was a young Warren Buffet’s mentor) and Dodd’s 1934 classic book, Security Analysis, in early 2002 and was awe struck by the timelessness of their writings. Considering the parallels between 2002 and 1934, I had to keep reminding myself that the book had been written almost 70 years prior. Let me share a montage of interesting quotes from the book (italics theirs): “…the prices of common stocks are not carefully thought out computations, but the resultants of a welter of human reactions. The stock market is a voting machine rather than a weighing machine. It responds to factual data not directly, but only as they affect the decisions of buyers and sellers…a conservative valuation of a stock issue must bear a reasonable relation to the average earnings. In addition, it must be justified by whatever indications are available as to the future. This approach shifts the original point of departure, or basis of computation, from the current earnings to the average earnings, which should cover a period of not less than five years, and preferably seven to ten years…But it is the essence of our viewpoint that some moderate upper limit must in every case be placed on the multiplier in order to stay with the bounds of conservative valuation. We would suggest that about sixteen times average earnings is as high a price as can be paid in an investment purchase of a common stock…it is difficult to see how average earnings of less than 6% upon the market price could ever be considered as vindicating that price. It would be acceptable only in the expectation that future earnings will be larger than in the past. In the original and most useful sense of the term such a basis of valuation is speculative .” [4]

Notice that Graham and Dodd heavily discounted expectations of future earnings. Maybe they were from Missouri and they never had to figure out what Google was worth but frankly I agree with their approach. It’s hard enough to know what a company really earned over the last 10 years, let alone project future earnings.

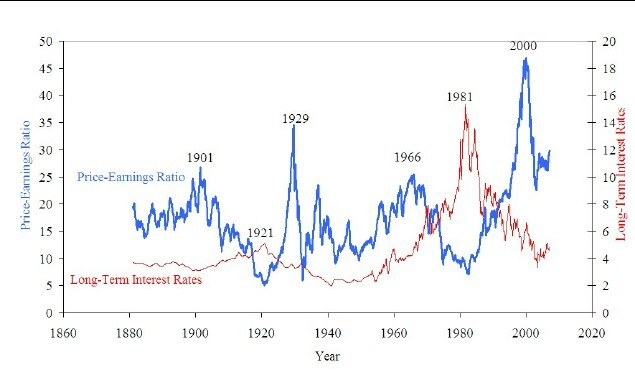

Fast forward to February 2006 at The CFA Institute Risk Symposium and Yale professor Robert Shiller discusses the characteristics of bubbles and how they propagate. He also presents a few compelling market valuation indicators. [5] (Shiller is famous for his 2000 book, Irrational Exuberance, named after a term used by Alan Greenspan in a famous speech. Interestingly, Shiller had discussed the impact of market valuations on returns with Greenspan two days prior to the famous speech.) First, he examines the S&P P/E ratios from 1881 — 2005, calculated as Graham and Dodd would have them calculated. The graph below, from Shiller’s Web site, is the same one used in his presentation but is updated through February 2007.

As you might expect, the graph shows massive fluctuations, with the most prominent peaks in 1929 and 2000. Of course there are two ways that a high P/E can come back down to earth – either the E can go up or the P can go down and you would have no way to know in advance which was going to occur. However, Shiller analyzed the relationship between the P/E and the subsequent 10 year return. Although the relationship would not make for a very good regression it clearly shows that a high P/E results in lower returns over the next 10 years. In particular, after the lows of 1919 the market averaged more than 15% per year and when the P/E was 20 – 25 the subsequent returns were near zero. So it would appear that Graham and Dodd were correct and that P/E is a valid indicator of fair value. By the way, as of February 2007 the P/E was at 30, which is not a positive indicator.

Shiller also presents his Valuation Confidence Index, which he has calculated since 1990 and which reflects the percentage of investors that believe the market is not overvalued.

Interestingly, the index bottomed out at around 30% right before the market peak in early 2000, which begs the question “if investors believed the market was overvalued then why didn’t they sell?” Maybe they didn’t believe in market timing. Unfortunately, his data only goes back to 1990 so we can’t be sure that this is a valid market indicator but it certainly bears watching. Note that by this measure the market is not currently at risk for a pullback.

In 2002 Pu Shen, an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, took the P/E indicator a step further and empirically examined the performance of a signaling tool similar to the Fed Model. For the period from January 1962 to December 2000 he tested buy/sell decisions based upon what he calls the “short spread” between the S&P earnings yield and the yield on 3 month treasuries (E/P – 3 month treasury bill yield). (He also looked at the “long spread”, based upon the 10 year yield but that was not as powerful.) He used the tenth percentile of the spread as the signal – i.e. when the spread dropped below the tenth percentile it was time to get out of the market and into 3 month treasuries and when it rose above the tenth percentile it was time to get back into the market. (Note that this is one of those binary strategies.) The idea here is that when the earnings yield on stocks is too close to the yield on 3-month treasuries stocks are not a very good investment. Seems reasonable.

Here is a summary of the important findings from his 39-page paper:

- The buy and hold strategy returned 1.117% per month over the test period while the switching strategy returned 1.322% per month.

- On an annualized basis that amounts to 14.26% vs. 17.07%.

- Whether or not you consider this difference to be statistically significant depends upon how you frame the analysis. I did not find this part of the paper particularly enlightening.

- The switching strategy resulted in a less risky portfolio over time. The Sharpe ratio of the switching portfolio was 0.205 vs. 0.13 for the buy and hold strategy.

Seems like it would be hard to pooh pooh these results. However, Pu also tested switching strategies based upon just the earnings yield and just the 3-month yield and concluded that almost all the predictive power was in the 3-month yield. His interpretation of this result is that trading based upon the 3-month yield keeps you out of the market during inflationary periods, which are not good for the market. I think it’s just as valid to view this from the perspective of higher yields mean a higher discount rate on stocks, which gives lower stock valuations.

While I think this study raises some interesting possibilities, I do have one major concern. Given the amount of historical data available and the varied economic environments that the market has encountered I don’t think 39 years is a long enough time period for this kind of study. In fact, Robert Shiller pointed out that “Since 2000, [the Fed Model] has broken down, and also before 1970, there really was not a correlation. Thus, people seem to have been exaggerating the impact of interest rates on the stock market.” [7] Clearly he is of the mindset that we should focus on the P/E ratio alone and from my perspective there is good reason to believe him. Interest rates are going to go up, they are going to go down, they are going to oscillate around some “normal” level, and you can’t very effectively predict where or when they are going to move. So you might as well take a long-term perspective and focus on the P/E ratio alone. Unfortunately, Shiller did not do nearly as rigorous an analysis as Pu.

A similar analysis from Ned Davis Research shows that extreme values of the S&P P/E can be effective predictors of future stock returns. Analyzing the period from March 1926 to June 2006, using trailing 12 month earnings, they point out that the average P/E has been 15.9 and they have set buy/sell triggers at P/E ratios of 9.3 and 20.2. (I was unable to discover how they determined these thresholds.) 24 months after responding to these triggers the median return of the S&P has been 27.5% after a buy signal and 0.8% after a sell signal.

So where does all this leave us today? The current trailing P/E ratio of the S&P 500 doesn’t look so bad at 15.6. However, based upon Shiller’s 10 year trailing analysis above which shows the February P/E to be 30, it’s clearly north of 30 now, which is darn high. The reason for the big difference is that S&P earnings have been on a rocket since 2002. As long as you have confidence that earnings won’t retreat then maybe valuations aren’t so out of whack. However, consider the data over the past 135 years:

Using Shiller’s entire data set I have determined that the historic earnings growth rate has averaged 1.45% per year and earnings are currently well above the trend line. Picking different time periods than the last 135 years can give slightly different results for the average earnings growth rate but nothing dramatically different. For instance, in a 2002 Yale ICF working paper Ibbotson and Chen stated that earnings have grown at a 1.75% annual rate since 1926. [8]

Each time that earnings have shot well above the trend line in the past they have eventually regressed back to the trend line. There are several reasons to expect that to occur. First, as Ibbotson and Chen point out, earnings just can’t grow faster than the overall economy unless equities are becoming a larger factor in the economy. While the factor share of equities has grown it is not a huge effect. Therefore, one would expect earnings to grow at about the rate of productivity growth, which has been about 2% per year. [8]

Second, market forces also throttle earnings growth. Extraordinary profits invite additional competition, greater employment levels eventually cause labor rates to rise, and high production levels bid up energy and raw material costs. With unemployment at a 6 year low and rising commodity prices we’re already seeing evidence of this.

My belief is that we have been experiencing an earnings bubble – perhaps driven by huge liquidity injections and lax home mortgage originations. It would seem that profits are destined to go down. If that’s the case then Graham and Dodd are correct to be looking at the longer-term earnings average. We could very well be at a market peak right now and, while a complete withdrawal from the market might not be prudent, reducing one’s exposure to stocks might be wise.

Disclosure: Author has a short position in SPY

[1] ING Special Report: Market Timing, July 2005

[2] William Sharpe, “Likely Gains from Market Timing”, Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. 31, No. 2, March-April, 1975, pp. 60 — 69

[3] Gary P. Brinson, L. Randolph Hood, and Gilbert L. Beebower, “Determinants of Portfolio Performance”, Financial Analysts Journal, Vol. 51, No. 1, January-February, 1995, p. 135

[4] Benjamin Graham and David Dodd, Security Analysis, 1934, pp. 452 – 453

[5] Robert J. Shiller, “Irrational Exuberance Revisited”, CFA Institute Conference Proceedings Quarterly, Volume 23, Number 3, September 2006, pp.16 – 21

[6] Pu Shen, “Market-Timing Strategies That Worked”, Research Division, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, May 2002

[7] Robert J. Shiller, “Irrational Exuberance Revisited”, p. 19

[8] Roger G. Ibbotson and Peng Chen, “Stock Market Returns in the Long Run: Participating in the Real Economy”, March 2002