Dividend Yield vs Cash Flow Why Investing For Dividends Is Not Your Best Bet

Post on: 18 Май, 2015 No Comment

New Zealand investors have a longstanding obsession with portfolio income; a bias which is exacerbated in a low interest rate environment.

Meeting a specific cash flow need is an important element of portfolio management. However, there are better ways to meet that need than by investing primarily to achieve dividends. In many cases, taxable investors with a cash flow need are better off minimising portfolio income.

Investors drawing down on their portfolios (e.g. retirees) need cash flow, which may originate from:

- Income (typically interest and dividend payments)

- Cash from the sale of securities

There are a number of factors to contemplate when determining how you might best use these components of cash flow to meet a specific need. However, investors often gravitate toward income investments before properly considering all the relevant issues, which can result in a less efficient investment solution. The following discussion addresses some important aspects of the income versus cash flow distinction.

In summary, Bradley Nuttall show that investing for dividends and high-interest to meet investors’ cash flow needs is a tax-inefficient and risky method. We explain how several popular theories around dividends are not accurate, such as:

- High dividend yield helps you avoid eating up your investment base to generate cash flow

- Dividends offer protection on the downside, and mitigate the drop in down markets

- High-dividend-yielding shares constitute a less risky investment because of the regular payments

- Dividend-yielding shares are worth more because they offer dividends

We argue that companies are valued based on their earnings. Whether those earnings end up in the left pocket (higher share price) or the right pocket (distributed as dividends) doesn’t matter from an overall value perspective.

Perhaps the best way to think of this is as a scale. To increase one side of the scale (dividends), you must balance it by decreasing the other side of the scale (share price). This is necessary because both are based on earnings. The more earnings distributed as dividends, the less earnings reinvested in the business (for future growth).

In short, what an investor gains as a dividend they lose in the value of their remaining shares. What does matter however, is the ability of a business to reinvest earnings (their investment policy) and the taxes investors pay as a result of which pocket the earnings fall into.

We show that investors should prefer taking capital gains, as they are a more tax efficient means of raising cash. Further, we demonstrate that high yielding shares are often the riskier choice. Thus, investing for yield can inadvertently lead to a riskier portfolio than is warranted by the client’s specific circumstances.

Do Dividends Matter?

Neither Apple nor Berkshire Hathaway (Warren Buffett’s firm) issue dividends. So why are they so valuable, if dividends are so important? It only takes a cursory read of national newspapers to realise that dividends are the sacred cow of the New Zealand investment landscape. The emphasis on dividends stems from the notion that a high-dividend-yielding share constitutes a less risky investment, due to the regular payments. Conventional wisdom dictates that the regular payment protects you on the downside, because if the share price declines, at least you have your dividend cheque. This perceived benefit leads many investors to place their emphases on dividends, regardless of whether or not they actually need cash flow. Those drawing cash from their portfolio are even more enthralled with high-dividend-yielding shares; if the regular payments can meet most or all of their cash flow need, then there is no need to sell and lock in a loss if the share price declines.

While this logic attracts many investors, it is empirically flawed. Dividend payments are not created out of thin air. Rather, they come from a company’s earnings or assets. When dividends are paid, the distributions reduce the value of the company by the amount of the dividend. 1

Capital Encroachment and Downside Protection

Part of the conventional wisdom mentioned above is that a high dividend yield may help you avoid feeling compelled to sell shares in order to generate cash flow. However, a dividend distribution (assuming you don’t reinvest) is like the company selling your shares for you! With a dividend, you may not have actually sold the stock yourself, but the economic impact is essentially the same as if you had.

Another common misconception is that dividends offer protection on the downside and mitigate falls in down markets. For example, if you own a share yielding 5%, your portfolio will be buoyed by this amount if the share price drops. However, consider that if the company did not pay a dividend, the price would have dropped less. You would obviously be out the cash from the dividend payment, but in both the dividend and no-dividend scenario, the total portfolio has dropped by more or less the same amount.

Investment Policy

A company’s dividend policy should not affect the overall value of your portfolio. However, while dividends don’t matter, what the company does with the cash in lieu of paying a dividend (i.e. its investment policy) does matter. The following passage from Nobel laureates Merton Miller and Franco Modigliani (M&M) succinctly sums up the concept:

Like many other propositions in economics, the irrelevance of dividend policy. is ‘obvious, once you think of it’. [Company] Values are determined solely by ‘real’ considerations—in this case, the earning power of the firm’s assets and its investment policy—and not by how the fruits of the earning power are ‘packaged for distribution.’ 2

The dividend irrelevance proposition is one of the key findings of M&M. While more recent papers suggest that dividends can affect firm value, this is more a result of what paying dividends signals to investors, rather than the dividends themselves. This signalling, however, relates more to changes in dividend policy (i.e. the dividend is being cut, increased, or initiated) than to the dividend versus no-dividend decision.

Risk and Return

While M&M describe dividends as merely a form of ‘packaging’ the fruits of a company’s earning power for distribution, dividends are often erroneously thought to be synonymous with profits. This misconception leads to the view that high-dividend-yielding companies are more profitable and less risky than non-payers when in fact, dividends are often not related to profits.

Very profitable firms may not pay dividends (e.g. Apple, Berkshire Hathaway). Conversely, some companies (or trusts) pay dividends (or distributions) in excess of profits. The latter case is unsustainable in the long run. Dividends must ultimately reflect a company’s ability to generate profits.

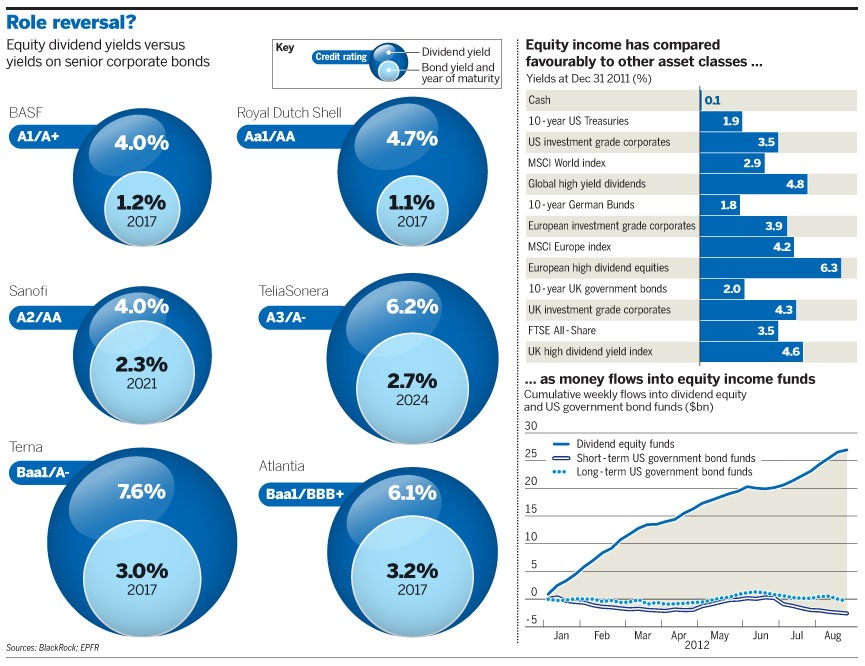

Furthermore, high-dividend-yielding stocks may in fact be riskier companies. Market efficiency suggests that the price, rather than the dividend, contains the information about the prospects for a company and its expected future cash flows. A high dividend yield (D/P) could be a reflection of a low price, rather than a high dividend.

The dividend discount model (DDM) shows how a high yield can result from:

- A high required return

- A low expected growth rate

- A combination of the above

Dividend/Price (i.e. Yield) = Required Return — Expected Growth

So a business that does not change its dividend but instead has a new, higher dividend yield, must have a lower price. The price is lower for one (or a combination) of two reasons; an increase in the required return, or a decrease in the expected growth rate.

Let’s say the higher dividend yield is the result of higher required returns. This would be a direct indicator that investors should consider the company a higher risk. High risk companies have low prices because investors consider the future prospects of the firm to be less bright. So in very simple terms, high yielding shares can be a direct result of increased risk.

But isn’t it a good thing if high yielding shares have higher expected returns? Not necessarily — only if an investor is aware of the risk and has chosen it purposefully, rather than having fallen into taking that risk accidentally through chasing dividends. Either way, investors must understand that the increased return is compensation for risk, not a direct outcome of the dividend policy of the business.

On the other hand, dividends may be high not because the shares are risky, but simply because growth prospects are low. Rational firms with low growth prospects often distribute dividends, as there are few good uses for the profits if reinvested in the business. These firms would not expect any increase in returns as a result of their high dividend yields.

International Evidence

Sorting shares by dividend yield in the US does not produce significant differences in average returns. This may suggest that a higher dividend yield results from a combination of a higher required return and a lower expected growth rate.

Sorting by dividend yield does correlate with higher returns in international markets, similar to the sorting of shares by other measures such as book value and earnings. Therefore, a high dividend yield may be mostly attributable to increased risk, rather than as a result of low expected growth.

So while many investors seek companies with high dividend yields because they want income from their portfolio, they must consider the risks they are taking to achieve that income.

There is however another, much better approach. It starts by recognising that investors need cash flow rather than income. Further, this method sets a portfolio’s risk as a deliberate target and does not unwittingly bias the allocation of the portfolio toward riskier companies.

Creating Cash by Selling Securities: Taxes, Costs, and Rebalancing

The alternative to meeting a cash flow need through dividend payments is to create synthetic dividends, by selling securities. This approach is often deemed undesirable because selling may result in locking in a loss if the stock price has dropped. As discussed earlier, this view is not empirically sound, as the dividend payment amounts to ‘packaging’ and doesn’t necessarily change the underlying (pre-tax) value of the portfolio.

However, the tax impact of synthetic versus regular dividends may result in different after-tax values, depending on the relevant tax rates applied to dividends and capital gains.

The highest marginal tax rate in New Zealand for individuals is currently 33%. Below, we calculate the cash tax burden — as a percentage of the distribution — with imputation credits for taxes paid at the corporate level netted off for a tax payer on the 33% marginal rate.

Eligible dividends from New Zealand companies*