Currency Hedging Has Many Ifs for Investors

Post on: 25 Май, 2015 No Comment

THE European fiscal crisis isn’t just raising investor concerns about how much foreign exposure to have, but also about how those bets should be made.

Historically, most individual investors have left their international holdings fully exposed to currency fluctuations. And for decades, this unhedged approach proved successful, as the dollar has lost roughly half of its value against a trade-weighted basket of global currencies since 1985. Whenever the dollar weakens, American holders of foreign assets stand to benefit simply on the currency exchange.

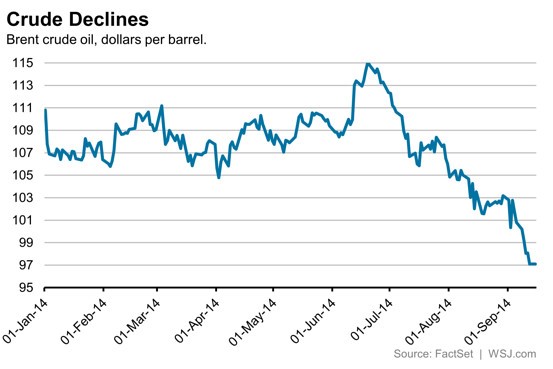

But thanks to Europe’s crisis, worries about the dollar’s strength have been trumped by more serious concerns about the euro ’s long-term viability.

The euro has lost nearly 7 percent of its value against the dollar in just the last three months. As a result, the 0.7 percent gain in European stocks since late August has effectively turned into a 6 percent loss for American investors.

Stock funds that hedge international bets — via contracts to sell the currencies with which they are making their foreign investments — are outperforming their peers. The Tweedy Browne Global Value fund, for instance, has lost just 6 percent so far this year, while the average foreign blue-chip stock fund is down around 11 percent.

Does this mean you should switch gears and start hedging? It depends on the assets you’re dealing with.

Michele Gambera, head of quantitative analysis at UBS Global Asset Management. notes that when it comes to equities, there are drawbacks to consider when hedging foreign bets back to the dollar.

For starters, he said, “you give up some diversification” — the kind you get by holding exposure to a basket of currencies, not just the dollar. This is a significant point. While global stock markets have been virtually moving in lock step with one another in recent years, currencies have taken divergent paths since the financial panic of 2008. So for stock investors, the currency effect is a crucial driver of diversification.

“There’s already a bit of a natural hedge in place among global companies or foreign companies that have large exports as part of their business,” said Christopher J.Brightman, head of investment management at Research Affiliates. He notes that while a German company like BMW may be linked to the euro, its exports stand to benefit if the euro declines and makes its cars more attractive to foreign buyers.

There are also costs associated with hedging. Among them are the transaction fees generated in buying currency futures, which add to an investor’s overall expense. There is also the potential for losing out on gains if the dollar reverses course and weakens again.

Some investors may see that possibility as unlikely, at least in the short run, given the euro concerns. But Alec Young, global equity strategist at Standard & Poor’s Capital IQ. points out that predicting currencies is even tougher in the short run than betting on stock price movements.

THOUGH the dollar has surged against the euro in recent months, it unexpectedly fell 15 percent between January and early May, as worries rose about Congressional gridlock and a potential United States default.

And over the entire year, the dollar has gained no ground against the euro, even though the debt crisis that struck Greece and Italy appears to be spreading to other parts of the euro zone. “Despite everything that’s happened in Europe,” Mr. Young said, “hedging really wouldn’t have helped.”

Meanwhile, the dollar has lost nearly 4 percent this year against the Japanese yen. So hedging a foreign portfolio would have erased any currency-related gains that American investors enjoyed in Japanese shares.

Yet Francis M. Kinniry, a principal in investment strategy at the Vanguard Group. says there is one case where hedging makes sense: in foreign bonds held by American investors. That’s because of the nature of bonds and the risks in currency moves.

Currency fluctuations don’t just affect potential returns; they can also add much volatility to a portfolio. In the case of stocks, though, that volatility tends to be dwarfed by day-to-day swings in equity prices. In fact, currency changes have historically accounted for only 12 percent of foreign equity volatility.

But bonds, by nature, are much more stable than stocks. So leaving a foreign bond portfolio unhedged and fully exposed to currency fluctuations could turn a docile investment into a much more volatile one.

Consider the Pimco Foreign Bond fund. Over the last five years, the unhedged version of this international portfolio has returned around 8 percent, annualized, versus just less than 6 percent for the hedged version of the same portfolio. Yet to earn those gains, investors in the unhedged fund had to expose themselves to more than twice as much volatility as those in the hedged one, according to Morningstar. (This is based on standard deviation, a common gauge of volatility.)

A recent Vanguard study found that since 1985, two-thirds of the volatility that investors have experienced in their foreign bond holdings has come from currency moves rather than swings in the fixed-income market.

In other words, an unhedged foreign bond does not always act like a fixed-income portfolio.

“If you decide to go unhedged, what you’re really doing is making more of a call on where you think the dollar is going than where you think foreign bonds are going,” says John Lovito, vice president and senior portfolio manager at American Century Investments.

As a result, Mr. Lovito recommends that investors hedge around 70 percent to 80 percent of their foreign bond holdings, with the remainder unhedged. That mix, he said, “has historically given you the best risk-adjusted returns.”

Paul J. Lim is a senior editor at Money magazine. E-mail: fund@nytimes.com.

A version of this article appears in print on December 4, 2011, on page BU4 of the New York edition with the headline: Those Euro Bets Have Many Ifs. Order Reprints | Today’s Paper | Subscribe