Creative Ways to Cut Your 401(k) Fees

Post on: 2 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Follow Comments Following Comments Unfollow Comments

What’s your 401(k)’s composite expense ratio? Higher than 0.1% a year? Then you should be looking for an escape hatch. It could save you a pile of money.

If the mere question about ratios leaves you flummoxed, you have company. Plenty of employees don’t pay attention to what they are losing to fund fees. They should. The difference between high-cost funds and low-cost funds could easily add up over the course of a career to several hundred thousand dollars.

The operators of retirement plans and even employers do not necessarily mind the state of confusion that prevails. One way or another the considerable paperwork cost of a 401(k) must be paid, and the most common way to do that is to extract it via fund expense ratios. The plan may offer a few bargain funds, yet still depend for its economics on having most of the workers wander blindly into higher-fee options.

To get your costs down, you may have to be a bit creative. Consider these real-life cases.

X, 23, has just joined a fast-growing West Coast technology firm. The pay is high, but the 401(k) plan is bad. There’s no employer match, and most of the funds on offer are expensive. Employees who sign up but neglect to make an investment choice are deposited into a balanced fund (a mix of stocks and bonds) that costs a rapacious 1.28% of assets annually.

Not wanting to pass up the valuable tax deferral, X is contributing the maximum $17,500 a year. She wants a mix of stocks and bonds. There’s one cheap stock fund available, an S&P 500 index fund at 0.09% a year. But the cheapest bond fund, American Century Ginnie Mae, costs 0.55%.

Solution: She will put her entire 401(k) contribution into the stock index fund. Then she will restore her balance by adjusting other assets. She has an inherited IRA at low-cost Vanguard. She’ll shift some of that money from stocks to bonds. With an investment of $10,000 or more, she is eligible for the bargain share class of the Vanguard Total Bond Market Index mutual fund. Annual cost: 0.08%.

Y, 37, is a new partner in a medical practice. There are all manner of compliance costs for retirement plans, and those costs must be recouped. The best the three docs could do was a menu drawn from the American Funds collection, priced at 0.58% to 1.13% a year.

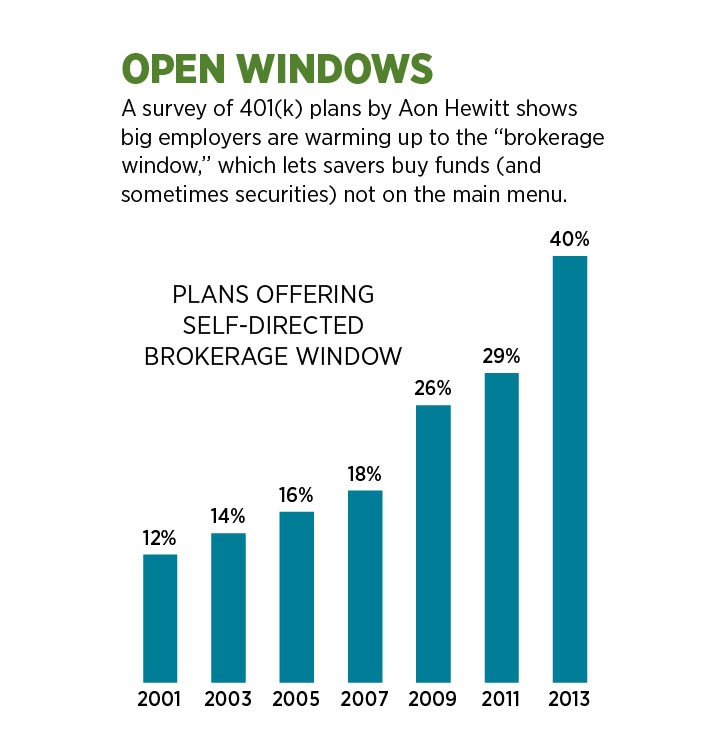

The doctor’s plan has an escape hatch. For a $100 transaction fee, a participant can use a “brokerage window” to buy just about any security. When his balance gets big enough, it will make sense for him to pay the fee and buy a dirt-cheap exchange-traded fund on the New York Stock Exchange. Schwab and Vanguard have ETFs costing as little as 0.05% a year.

Suppose Dr. Y moves $100,000 over to the Schwab U.S. Aggregate Bond ETF, with an expense ratio of 0.06%. His annual portfolio cost will go from $580 (or worse) to $60. He’ll gladly pay the $100 transaction fee, a brokerage commission and a bid/ask spread of a few cents per ETF share.

Z is a 61-year-old manager at a nonprofit with a Fidelity-managed 403(b) plan, something very similar to a 401(k). The menu includes some low-expense stock index funds. But the cheapest fixed-income choice is the Fidelity Intermediate Bond Fund at 0.45% a year.

The $500 million plan has a brokerage window with a $75 fee. This window is opened just a crack: Z may not buy ETFs, and when he gets a Vanguard fund he is herded into the expensive share class.

Last year Z crawled through the window with $172,000, putting the money into the Vanguard bond market index fund at an expense ratio of 0.2%. His savings will run to $430 a year.

A survey by benefits consultants Aon Hewitt found that 76% of large employers have workers pick up all the costs of 401(k) administration. Among employers that push all or some of the costs onto employees, a rising minority (now 26%) assess account administration fees, such as $25 per account per year. The rest continue the tradition of burying costs in overpriced funds, a practice that helps youngsters with tiny balances but hurts workers who have been around long enough to accumulate respectable sums.

Says David Gray, a vice president in Charles Schwab’s retirement business: “We’re seeing less and less of a tendency to subsidize 401(k) administration with fund fees and more and more transparency in costs.”