Cracks in the Pipeline Part Two High Frequency Trading

Post on: 30 Май, 2015 No Comment

Cracks in the Pipeline Part Two: High Frequency Trading

This is the second of a series of articles, entitled “The Financial Pipeline Series”, examining the underlying validity of the assertion that regulation of the financial markets reduces their efficiency. These articles assert that the value of the financial markets is often mis-measured. The efficiency of the market in intermediating flows between capital investors and capital users (like manufacturing and service businesses, individuals and governments) is the proper measure. Unregulated markets are found to be chronically inefficient using this standard. This costs the economy enormous amounts each year. In addition, the inefficiencies create stresses to the system that make systemic crises inevitable. Only prudent regulation that moderates trading behavior can reduce these inefficiencies.

Introduction

The prior article in this series points out that the most important social purpose of the financial markets is to facilitate the movement of funds from (a) holders that seek investment opportunities to (b) businesses and governments who need to put investment capital to work in productive ways and to individuals who seek to borrow for their current needs. This function is referred to in this series as “Capital Intermediation.” The article describes findings that the cost of Capital Intermediation has increased significantly over the 35 years of financial market deregulation in the United States, despite advances in information technology and quantitative analysis that intuitively should have increased efficiencies in the process. Instead, Capital Intermediation has become less efficient.

Academics speculate that this increased cost must have something to do with the massive increase in trading in the securities and commodities markets over this period. This is correct, but incomplete. Volume, per se. has not caused Capital Intermediation to become more inefficient. Rather, particular types of trading that generate tremendous volumes have caused it. Thus, observed high trading volume includes — actually is dominated by — specific types of trading that increase the inefficiency of Capital Intermediation and its cost. The increased volumes in the traded markets are largely a result of high-speed, computer driven trading by large banks and smaller specialized firms. This article illustrates how this type of trading (along with other activities discussed in subsequent articles) extracts value from the Capital Intermediation process rendering it less efficient. It also describes how the value extracted is a driver of even more increased volume creating a dangerous and powerful feedback loop.

Tying increased trading volume to inefficiencies runs counter to a fundamental tenet of industry opponents to financial reform. They assert that burdens on trading will reduce volumes and thereby impair the efficient functioning of the markets.

The industry’s position that increased volume reduces transaction cost is superficial, if not negligently or intentionally erroneous. Its position is based on a simplistic syllogism: all trading volume increases market liquidity, market liquidity reduces transaction costs and reduced trading costs benefit the economy. But there are critically important distinctions between trading volume and levels of market liquidity; and trading activity that increases the cost of Capital Intermediation, even though it may reduce transaction costs, does not necessarily benefit the economy on a net basis.

This article will explore the concepts of volume and market liquidity, including critical distinctions between them. Liquidity benefits market participants. A market is considered liquid to the extent that there are levels of buying and selling interest sufficient so that one who wishes to transact can be assured that he or she can complete the transaction close to the price most recently quoted on the market. Another way to think about liquidity is that it provides stability of prices within the current spread between reliable purchase and sale price quotes. Predictability and stability are closely related.

Deregulation and technology advances have greatly increased trading volume. However, this article will show that much of today’s historically high trading volume does not provide market liquidity when markets are under stress — that is to say at precisely the time that liquidity is most needed. On the contrary, this large category of trading volume reverses itself and consumes market liquidity in great quantities at these times. The shift from providing liquidity to consuming it is unpredictable and, as a result, even more disruptive. And these shifts occur on a daily basis.

Furthermore, a substantial portion of this volume is specifically designed to subvert the essential price discovery function of the marketplace. Price discovery allows market participants to observe market prices levels at a given point in time. In a well-functioning market, price levels reflect the fundamental value of securities and derivatives being traded based on currently available information that is relevant to fundamental value.1 Even when the market is not stressed, commonly used high volume trading tactics drive market prices away from the fundamentally sound values that efficient markets achieve. As a result, the price levels discovered by market participants are distorted by market maneuvers and are unreflective of fundamental values, reducing market efficiency.

Finally, in order to avoid these tactics, many market participants have opted for “Dark Pools” and trading that is internalized to broker/dealers. In each of these trading venues, price quotes and orders are hidden from the general market. These are alternatives to “Lit Venues,” i.e., exchanges and transparent trade matching venues in which quotes are disclosed. This reduces price transparency overall. Notwithstanding some analytical work that has been interpreted to the contrary, the migration of trading price data to Dark Pools and internalization programs damages essential price discovery.

Chronic price distortions are not merely vehicles for clever traders to get the better of slower and weaker market participants. Distortions caused by illusory liquidity, aggressive trading tactics and non-transparent trading make the marketplace unreliable. There is ample evidence that major securities and derivatives markets in the US are widely viewed as unreliable. In response, investors adjust the prices required to induce them to deploy their funds so as to provide a buffer against unreliability. This is a drag on productive investment in businesses, governments and households. It is also a direct transfer of value from the productive users of capital (and ultimately the American public) to the financial institutions that exploit (and quite often create prior to exploiting) these price distortions.

Trading Volume in the Era of Deregulation

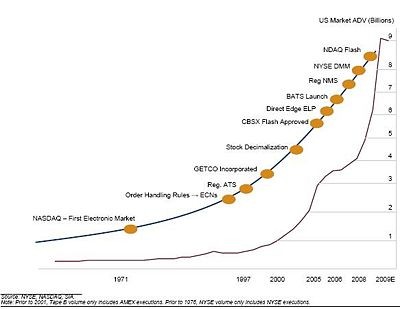

Across all markets, trading activity has increased enormously during the time of deregulation. Equities markets are the deepest and most liquid securities markets. Trading in the US equities markets has reached extraordinary levels. (See Figure 1)

This has not been because of new issues of shares that would have increased the amount of equities available to trade. The supply of new issue equities has been relatively low for years. (See Figure 2)

20Shot%202013-03-06%20at%207.01.21%20PM.png /%

20Shot%202013-03-06%20at%207.01.28%20PM.png /%

It is abundantly clear that equities trading volume growth is a function of algorithmic and high frequency trading (“HFT”). This technique, developed over the last two decades, is employed widely in the markets. It is characterized by fully automated trading strategies intended to profit from market liquidity imbalances or other short-term pricing inefficiencies. 2 It has been estimated that today 73% of equity trading volume is a result of algorithmic and high frequency trading. 3 HFT has changed fundamental characteristics of markets. It has been estimated that at the end of the Second World War, the average holding period for stocks was 4 years. By the turn of the millennium, it was 8 months. By 2008, the average holding period declined to 2 months. And it has been estimated that, at least for actively traded shares, it had declined to 22 seconds by 2011. 4 Obviously, trading that churns the market has increased tremendously.

While there has been speculation that high frequency trading may have declined recently, a November 2012 study funded by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission focusing on the equities futures market, an integral element of the equities market, finds that the percentage share of HFT in that sector has remained constant. 5

Bond market trading has increased as well. From 1996 through 2008, annual trading volume in bond markets increased by 3.13 times, though trading declined in 2009 and 2010 because of the financial crisis effects on the Federal Agency and Mortgaged Backed Securities markets. Over the same period, new issuance increased by 2.8 times. 6

The derivatives market volume growth is even more dramatic. The new issue/trading comparison is irrelevant in this instance since derivatives are not assets that are bought and sold. They are bilateral contracts to be performed in the future. (See the third article in this series for an in-depth analysis of derivatives.) A party does not actually buy a derivative from someone else, as one might with shares of stock or bonds. Every transaction is a new position. The outstanding notional amount of financial (non-commodities) derivatives in 1987 was $866 billion. By the beginning of 2010, the amount was $466.8 trillion. 7

Thus, volumes in all traded markets have increased dramatically during the period of deregulation while the efficiency of Capital Intermediation has declined. As indicated by Professor Philippon of NYU, the declining efficiency of intermediation must be related to the incremental quantity trading and its properties. 8

Basic Concepts: Liquidity and Bid/Ask Spreads

Contrary to the Efficient Market Hypothesis, the evidence indicates that increased volume of trading activity is not a universal good. There is no doubt that a portion of the volume traded by purely financial market participants facilitates the efficient intermediation of capital transfers between suppliers and productive users. But, as we shall see, not all incremental volume has this effect. Before we delve into this issue, a review of some basic properties of trading markets is needed.

The concept of market liquidity is misused and abused almost universally by the financial services industry, experts and commentators. It refers to the extent to which the initiation of a market transaction changes the transaction price that would be expected based on recent price quotes that are widely known. If, for example, a large number of willing buyers are active in a market at a given price level, a seller is more likely to receive the going price for a sale he or she posts to the marketplace seeking a transaction counterpart. In this circumstance, the buying and selling interest in the market is so large that the transaction is unlikely to exceed the level of willing buyers or sellers at the best available reliable price.

Conventional thinking is that a large number of transactions taking place in a market means that transaction liquidity is high and the seller is more likely to receive the price most recently bid to other sellers when his or her posted offer to sell is matched with a buyer. As we shall see, this is exceedingly simplistic.

Bid/ask spreads are related to market liquidity. A bid price is an offer to buy an amount of securities or derivatives at a stated price. An ask price is a similar offer to sell. Bid and ask prices are posted on exchanges or other Lit Venues so that prospective entrants to the market can see the most reliable expected acquisition cost or expected sale price if they choose to transact. The size of the prospective entrant’s transaction is important to the extent it consumes all of the purchasing interest or sale interest at the published bid and ask levels. If this happens, the price will be less favorable than indicated by the best priced quotes since additional buying or selling interest will have to be attracted to fulfill the transaction.

A bid/ask spread describes the price range between actual recent transaction proposals, both to buy and to sell, in a marketplace. (See Figure 3.) There is reasonable certainty that some amount of securities can be sold at the bid price and that some amount can be purchased at the ask price, assuming that quantities do not exceed posted bid or ask quantity limits. If an investor interested in buying shares of “AET” looks at this screen, he or she sees that the last purchase and sale was at a price of $13.01 per share and that the current asking price is $13.02 per share. The investor also sees that there are offers to buy AET, or bids, at $13.01 per share, so he or she should expect to buy AET shares at a price somewhere between $13.01 and $13.02 unless his or her order is so large that it wipes out the $13.02 ask quotes and a higher price is required to attract more sellers. In that case, the market liquidity was insufficient to allow the investor to acquire the shares at the quoted price. (See Figure 3)

20Shot%202013-03-06%20at%207.01.39%20PM.png /%

Bid/ask spreads are thought to be narrower in highly liquid markets. Competition to profit from the spread between bid prices and ask prices in highly liquid markets is greater. And resale/repurchase is more reliably accomplished if the trader wishes to do so at a subsequent time, which has a significant value that is an independent component of the price paid or received at the execution of the transaction. For example, a purchaser will pay less if the market is illiquid because the ability to realize any gain at a subsequent time is less certain.

Bid/ask spreads are a measure of transaction cost. 9 Financial institutions have historically engaged in the business of simultaneously quoting both bid and ask prices. The financial institution will sell at the ask price and immediately cover the sale with a purchase at the bid price. This activity is called market making, a trading strategy designed to capture the spread between the two quoted prices. The market maker provides other market participants immediate and reliable access to a purchase or sale at the going price at the moment of execution. It is said to provide “liquidity.”

Conceptually, the price that the market “charges” a transacting market participant a price paid in exchange for access to liquidity (e.g., making the securities available at a reliable and predictable price). It is the spread between the bid and ask prices, or the profit a financial institution would earn if it immediately covered the purchase or sale at these reliable levels. (See Figure 4)

20Shot%202013-03-06%20at%207.01.50%20PM.png /%

This is not necessarily the result in any given transaction. Purchases and sales are consummated inside and outside the bid/ask price spreads, sometimes because a market entrant seeks to transact in quantities in excess of the purchase or sale interest level at the best prices currently quoted by market makers. However, the bid/ask spread is the generally accepted quoted cost for consummating a transaction that market participants rely on.

Many market participants assume that higher levels of buying and selling interest reduce transaction costs as measured by bid/ask spreads. Recent studies have described the effect of changing volume levels on bid/ask spreads, but it is an extremely complex relationship. 10 It is certain that the relationship between volume and bid/ask spreads is far from linear. It is also clear that factors specific to the security or derivative being traded have a substantial effect on the relationship. For example, if the economy is booming, bid/ask spreads may be narrow for lower credit quality bonds. But, if the economy is shaky and there is an increased risk of corporate defaults, the bid/ask spreads for those bonds may be wide even if the available liquidity is the same. This is because financial institutions who quote bid and ask prices (i.e., market makers, as described above) must price in the uncertainty of a credit event intervening in the process of covering off a position.

There are other attributes of trading volume that affect both the cost of transactions and Capital Liquidity. These are explored below.

Trading Volume and Transaction Liquidity

Conventional analysis of market efficiency centers on the instantaneous price effect of liquidity on individual transactions by examining quoted bid/ask spreads. The term “Transaction Liquidity” will refer to the trading volume that narrows the spread between the bid and ask prices, thereby reducing transaction costs. 11

Some types of trading activity always reduce transaction costs because of the design of the activity. Other types of trading activity only sometimes reduce individual transaction costs. At other times, however, these types of activity have profound negative consequences for transaction costs. They are almost never neutral. Another way to describe this type of trading activity is that it switches back and forth between providing liquidity and consuming it. On the whole, the actual and threatened negative consequences from abrupt and unpredictable shifts from providing liquidity to consuming it distort the market so profoundly that they significantly increase the cost of Capital Intermediation.

Finally, a third category of trading employs strategies that are intended to distort market prices and then take advantage of the distortion. These types of trading generate no value to anyone other than the trader pursuing the strategy. These types of trading activity may be neutral in terms of its effect on transaction costs; but they always increase Capital Intermediation costs.

Liquidity Providers and Liquidity Takers

Market participants that routinely post reliable and meaningful offers to buy or sell at the going prices are liquidity providers. Market participants that do not routinely post such prices to buy and/or sell are liquidity takers. An investor who enters the market intermittently, only when he or she needs to transact, is an obvious liquidity taker. Such an investor can be referred to as a “Value Investor.”

At high levels of market liquidity, bid and ask prices are reliable; and the difference between expected minimum sales prices and expected maximum purchase prices – the bid/ask spread — is generally thought to be narrow. This is because the difference between those prices represents the profit that should be received by a special class of market liquidity providers who are in the market only to accommodate buyers and sellers. Such a liquidity provider is called a “Market Maker.” Market Makers provide resting orders to buy and sell at prices that bracket their profit expectation. The orders are “resting” because they are made available for a period of time. Their business model is to buy at the going price and immediately sell at the going sale price, profiting from the difference.

By doing this, Market Makers provide certainty to the marketplace. For example, a Value Investor is assured that he or she can transact within a range of known prices. Diverse and robust Market Maker interest, competing to profit from the difference between the price to purchase and the price to sell, tends to narrow the difference between bid and ask prices (though other, more powerful forces can intervene).

A trader who is continuously in the market seeking to profit from short term market strategies does not have to be motivated exclusively by the prospect of profiting from difference between current buy and sell prices, as a Market Maker is. That kind of trader expects to profit from information in his or her possession predictive of changing price levels and trading strategies designed to extract the value of that information. They profit from other market participants who lack this information or the means to extract its value. These market participants can be referred to as “Information Traders.”

An empirical study of the Taiwan stock exchange concludes that “[w]e have shown that dealers do not provide liquidity to the market; instead, they trade on information.” 12 The authors note that this behavior is particularly prominent during times of stress. The distinction being drawn is that the traders are not motivated by the profit potential from Market Making, a pure form of intermediation that is a low risk, stable profit business. Instead of providing liquidity in exchange for the bid/ask spread, the dealers in the study trade for the purpose of taking on positions and profiting from changes in market price. Their strategy is to profit from superior information. Information Traders only provide liquidity serendipitously (and, as pointed out in the study, unreliably, especially in stressed conditions when it is needed the most). The study is consistent with the general view that Market Making has declined in importance, being replaced by the less reliable, serendipitous liquidity provided by Information Traders. Market Making has become more risky because of persistent and serious market distortions, described in detail below.

It is obvious that a market participant is a liquidity provider only if the prices he or she quotes can be relied upon by other market participants, specifically Value Investors and those Information Traders who at the time are acting as liquidity takers. A price quote that appears on a screen is useless as a source of liquidity if it is not available when it comes time to transact. An Information Trader provides meaningful liquidity when his or her quoted prices represent levels that are reliable and meaningful to the participants who are liquidity takers. Sometimes an Information Trader provides such quotes and sometime it does not. When it is active, but not providing such quotes, it is a liquidity taker.

The following chart describes the categories of market participants.