Complete investment guide for all Commodity ETF and ETN securities

Post on: 23 Май, 2015 No Comment

When most people think about what determines the price of a particular commodity such as gold or crude oil, they only consider supply and demand economics. This is after all what we’re most familiar with: when summer comes around and the weather warms up, we get into our car more often and go for a drive or a longer road trip. Since we use more gas during the summer months, demand is up. Gas stations respond by jacking up the price of gasoline.

Another example many of us are familiar with takes place during the cold winter months. To heat our homes, we use more energy, using commodities such as natural gas or heating oil. Since we use more of them for heating purposes, this increases demand and, you guessed it, drives up the price for those commodities during the winter season. If you look at long term charts for energy commodities, it becomes clear that prices follow this cyclical pattern with seasonal spikes.

But commodity prices don’t always follow a predictable pattern, because changes in supply and demand often are independent. For example, several years ago, oil and gas exploration companies developed the hydraulic fracturing technology required to extract shale gas. Gas production soared, and the increase in supply has driven natural gas prices (including those of natural gas ETFs ) to ten year lows.

A fair market price is set based on supply and demand for the commodity. Or as Karl Marx once put it: “From the taste of wheat it is not possible to tell who produced it, a Russian serf, a French peasant or an English capitalist.” And so the price of wheat for two equivalent bushels should be the same.

But in addition to the supply/demand equilibrium, there is another important factor at play: speculation. Take for example gold. Sure, there is high demand for the metal in electronics and other industries, as a currency reserve, and for other reasons. But there are also a lot of investors who are simply attracted to the rising price of gold, and want to “get in on some of that action.”

There are now over 70 billion U.S. dollars invested in the most widely held gold ETF. That means that through this one exchange traded security, investors now own more gold bullion than the reserve bank of most large nations such as China, Russia, Switzerland, or Japan!

Popularity feeds on itself. The financial media are out in force, advertising gold ETFs in newspapers, magazines, and on TV shows. If that’s not speculation, I don’t know what is.

Another example of a speculative run-up in commodities was when hedge fund managers (and others) in 2007-2008 loaded up on commodities, fueling a massive increase in their prices. When they all exited in mass during the next year (as the global economic crisis unfolded) the prices of many commodities plummeted, and have still not recovered to this date. Commodities are not the only market that exhibits speculative behavior. We’ve seen it in stocks (think Nasdaq dot-coms in the late 1990s), real estate, tulip bulbs, you name it.

In summary, the price of commodities is determined not just by fundamental reasons, but also speculation by various participants in this dynamic market. Sometimes the speculative return component drives commodity prices far beyond any reasonable valuation, leading invariably to an eventual collapse of the bubble.

In this article I’ll take a look at how commodity index funds have performed when compared to an investment in U.S. stocks. The equity benchmark I’ll use is the S&P 500 Total Return index, which measures the performance of the 500 largest U.S. stocks, including their dividends.

First up is the Powershares DB Commodity Index Fund (DBC), which was introduced in January 2007. It is currently the most popular commodity index fund, with 6.39 billion dollars under management, an annual expense ratio of 0.85% and average trading volume of 2.5 million shares per day. Between inception and its peak in mid 2008, the fund gained over 100% in value. But its subsequent decline of over 60 percent was more severe than that of stocks during the same period (the S&P 500 lost 55% of its peak value). Still, an investor in DBC would have fared better than a U.S. stock investor, as can be seen in the chart below.

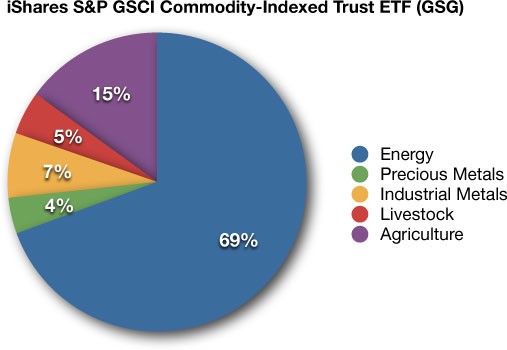

Lets now take a look at is the iShares S&P GSCI Commodity-Indexed Trust (GSG), which also started trading at the beginning of 2007. With 1.42 billion dollars in assets under management, this is the 2nd most widely held commodity index ETF. Its expense ratio of 0.75% is slightly lower than DBC. With an average of 408,000 shares trading hands per session, it is also less liquid. Like DBC, this fund had a sharp run up until the summer of 2008, more than doubling an investor’s money. But it’s subsequent decline was even more severe: it lost over 71 percent of its peak value within a matter of months. The volatility of GSG (annualized standard deviation) is 29.4%, higher than that of the S&P 500 (26.2%). Commodities in general have not appreciated as much as stocks since March 2009, and as a result, an investment in the S&P 500 has outpaced GSG since inception, as shown in the chart:

Commodities add some value as a means to diversify a portfolio. You can see this clearly in the above charts: both DBC and GSG continued to rally during the first half of 2008, long after the bear market in U.S. stocks had already started. In retrospect, part of this return appears to have been speculative investments by hedge funds and other players. Still, when risky assets started to be sold off across the board in the second half of 2008, commodity funds provided no shelter or buffering for an investor’s portfolio.

In summary, by these measures you can see that commodities can certainly enjoy large gains during a short time period, but they are also riskier than large cap stocks, w.r.t. their volatility and maximum drawdown.

Many investors turn to ETFs as a convenient way to participate in the gold market, without having to be exposed to the inconvenience and risks of buying and storing physical gold bars or bullion, or the complications of trading gold futures contracts. The first gold ETF was listed on the U.S. market in November 2004: the SPDR Gold Fund (GLD). The GLD fund has become so popular that it is now the second most widely held ETF in the world, with over 70.6 billion dollars under management. As a comparison, that’s more than the entire gold reserves of China! GLD invests in physical gold bullion, and the gold bars are held in the vaults of HSBC bank in London. If you’re so inclined, you can actually go to the website of SPDR Gold Shares and view a document listing every bar currently held by the fund (the file is over 1,700 pages long!) Each GLD share represents 1/10th of an ounce of gold.

The chart above shows the performance of the GLD ETF since it started trading. An investor who had bought GLD shares in November 2004 would be looking at an over 300% gain by August 2011. Gold prices have come down a bit since then, but are still holding on to a very healthy 279% gain since 2004. That’s a compound annual return of just over 20 percent. With returns like these, it is no wonder that investors are flocking to the GLD ETF.

Next, we’ll take a look at how gold has performed compared to U.S. large cap stocks (represented by the S&P 500 index). As you can see, the S&P 500 compound annual return of 3.59 percent is barely noticeable compared to the stellar performance of gold:

It is also worth noting that even during the most severe price declines of the 2008-2009 recession, gold declined no more than 27.7% from its peak value, compared to a loss of 54.6% for U.S. stocks. OK, now lets look at some other popular gold ETFs.

Another very popular gold ETF is iShares COMEX Gold Trust (IAU). with 9.7 billion dollars under management. This ETF began trading in January 2005. Like the GLD fund, IAU also invests in physical gold bullion. The cost of securing and storing gold is significant and creates a performance drag on all gold ETFs that invest in the physical metal. Investors should be aware that the annual expense ratio of IAU is 0.25%, significantly lower than the 0.40% for GLD. If your goal is to establish a long-term position in gold, then IAU is definitely the way to go as it will outperform GLD and SGOL (see below) over time due to its lower expense ratio.

Up next is the ETFS Gold Trust (SGOL). which was introduced in September 2009. Even though this is a fairly recent addition, SGOL has already accumulated about 1.9 billion dollars under management, making it the third most widely held gold ETF. Like GLD and IAU, this fund also invests in physical gold bullion, and stores its gold bars in secure bank vaults in Zurich, Switzerland. With an annual expense ratio of 0.39%, it’s also not as efficient as the IAU fund.

The PowerShares DB Gold Fund (DGL) is a different kind of gold ETF. Rather than holding physical gold bullion, this fund trades gold futures contracts. Lets compare it to GLD and see how that’s worked out so far:

Hmmmm. Not so good for the DGL fund, as you can see in the chart above. It has trailed the GLD fund significantly since its inception date in January 2007. An investor in DGL would have ended up with 23.1% less in gains over this time period. That makes bullion funds like IAU and GLD much better candidates for most gold investors. But there is one caveat: taxation. In the U.S. gold bullion is classified as a collectible, and is taxed at a rate of 28%, much higher than the normal 15% long-term capital gains tax on other securities, so ETFs like GLD and IAU are subject to this high rate. The tax treatment of futures based ETFs is complex (and I’m not an accountant, so seek professional help!). In general, gains and losses in a fund like DGL would be treated as 60% long-term and 40% short-term capital gains, giving it an edge in tax efficiency over bullion funds. However, judging by the large difference in actual performance, I would say that bullion funds are still a better investment option. Investors seem to agree: as of this writing, the DGL fund has about 410 million dollars under management, less than 6% the amount invested in the GLD fund.

The last gold fund we’ll look at today is the Market Vectors Gold Miners ETF (GDX). This is an index fund that invests in the common stocks of companies involved in the gold mining industry. It replicates the performance of the NYSE Arca Gold Miners Index. As you’d expect, this fund behaves differently from a pure gold bullion ETF:

Since its inception in May 2006, it has significantly lagged the price of gold (as represented by GLD), and has compounded at a mere 7.54% annual rate, compared to 18.16% for GLD over the same period. What should also be obvious from the above chart is how fast and far the gold miners dropped during the economic recession in 2008-2009. The GDX fund had a maximum drawdown of 68.45%, much higher than the 27.73% in GLD over the same period (and also worse than the performance of stocks). GDX’s volatility (annualized standard deviation) is also more than twice as high as GLD. Also notable is the fact that the gold miners have basically been trading in the same range since the end of 2010, whereas the price of gold has continued to enjoy significant gains since then. Still, the GDX has accumulated 9.63 billion dollars in assets under management.

Some investors describe GDX as a “leveraged play on gold.” It costs the mining companies a certain amount of money per ounce to extract and refine the metal, and beyond a certain point, as the price of gold rises “everything else is gravy.” I’ve seen this effect in 2002-2004, before the price of gold really took off. If you can identify small, barely profitable mining companies early on in an uptrend, watch out! But there are other factors at play. Gold miners are generally speaking not U.S. companies (many are in Canada, South Africa, and elsewhere). That makes an investment in GDX subject to some currency risk (the value of the US dollar compared to foreign currencies).

Conclusion

So far, we’ve looked at five of the most popular gold ETFs. Both IAU and GLD are excellent “pure play” ways to invest in the gold market, and I give the nod to IAU because of its significantly lower annual expense ratio. The last time I checked, there were 51 different ETFs and ETNs to trade gold! In addition to bullion funds, futures based gold funds, and gold miners, there are inverse (short) ETFs, leveraged products (2x, 3x exposure), and a number of other ways to invest in (or bet against) the shiny metal. But that’s the subject of a future blog post.

Most investors interested in natural gas ETFs are familiar with the funds that track natural gas futures contracts. Popular examples include the United States Natural Gas ETF (UNG) and iPath Dow Jones UBS Natural Gas ETN (GAZ).

But this is not necessarily the best way to invest in this sector of the commodities markets. The price of natural gas has declined in recent years, and an investor who has bought these funds would be having a tough time, as shown in the historical price chart of UNG below:

Since it started trading in May 2007, the UNG fund has lost 94% of its value. And an investment in GAZ would have fared the same. (The performance of the GAZ fund closely mirrors UNG, although it was launched a few months later in October 2007).

This poor performance is in part due to the price of natural gas futures, which have been in decline since 2008. But that’s not the only reason. As you can see in the graph below, on a percentage basis, the UNG fund has decreased a lot more than the price of natural gas futures, even though it is supposed to track these commodities closely:

That’s not the way an index fund should look when compared to its index; the performance should be virtually identical. Again, we don’t mean to pick on UNG, the GAZ fund performs just as poorly.

Why the huge discrepancy? Why is the ETF price so different from the natural gas futures it is supposed to track? Is it due to the expense ratio of the ETF? That’s part of it. These ETFs have relatively high expense ratios, which will definitely create a drag on the price. In the case of the UNG fund this costs and investor 0.85% per year, and 0.75% for GAZ. But that doesn’t explain the entire difference.

So what else is going on here? In a word: contango. Contango refers to a situation that occasionally happens when futures contracts are rolled over from one month to the next. Since the UNG and GAZ ETFs both hold natural gas futures contracts, they need to roll these contracts forward every month as the old contract expiration date approaches. New contracts sometimes have a slightly higher price than the old one, and this is what is known as contango. Each time the ETF managers roll into a new contract, it costs them a bit more, and these price discrepancies create a huge performance difference over longer periods of time. This is clearly shown in the chart above, where the price of natural gas futures declined 60% during this period. That’s bad, but not nearly as awful as the 93% decline in value of the UNG fund during the same time!

So what is a natural gas investor to do? Fortunately, there is a better way to invest in this commodity.

A better way to invest in natural gas

Enter the First Trust ISE-Revere Natural Gas Index Fund (FCG). This ETF has been on the market since May 2007. What’s different about this fund is that it invests in stocks, not futures contracts. More specifically, it aims to track the ISE-REVERE Natural Gas Index, which consists of stocks that derive a substantial part of their revenue from the exploration and production of natural gas. The index includes some household names like ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips, and Royal Dutch Shell. Sure, these companies engage in oil exploration also, so in that regard, the FCG ETF is not a “pure play” on natural gas. But it sure performs a lot better than the futures based natural gas ETFs. Lets compare the historical performance of FCG against the UNG fund, since inception:

There. Isn’t that better? Since inception, FCG is about at break-even (minus 4%), while UNG has lost 94% of its value. More importantly, FCG has appreciated significantly since the bear market bottom in early 2009, while UNG just continues to decline.

In summary, investors interested in a natural gas ETF should seriously consider the FCG fund, and stay away from futures-based funds like UNG and GAZ. Frankly, I’m a bit puzzled why investors have poured 1.06 billion dollars into UNG (its current assets under management), whereas FCG has attracted a relatively modest $354 million. And if you’re looking for a natural gas pure play, stick to the actual futures contracts.

Commodity index funds purchase futures contracts to track the price of a broad basket of commodities. There are currently more than 10 exchange traded funds of this kind. Each fund tracks a different underlying index, and the specific commodities and weights vary significantly. In this post, I’ll take a closer look at the top four commodity index funds, ranked by total assets under management:

- PowerShares DB Commodity Index Tracking ETF (DBC)

- iPath Dow Jones UBS Commodity Index ETN (DJP)

- iShares S&P GSCI Commodity-Indexed Trust ETF (GSG)

- Elements Rogers International Commodity Index ETN (RJI)

Index Weights

When analyzing a commodity index fund, it helps to group its holdings into five major categories: Energy, Precious Metals, Industrial Metals, Livestock, and Agriculture. While all these funds track a broad basket of commodities, their composition varies significantly. The table below shows these differences, by looking at the percentages allocated to each major commodity category: