Benefits of DollarCost Averaging

Post on: 13 Август, 2015 No Comment

Q: I recently sold my house in San Francisco for a substantial sum. I currently am renting and may not purchase another property in the future. I want to invest in the stock market but wonder what is the best way to do it. Should I invest the entire sum at once, or should I spread it out over several months and take advantage of dollar-cost averaging?

A: Because the stock market tends to rise over the long term, the most logical move would be to invest all the money at once. There’s a better-than-even chance that shares you buy now will be worth more when several months have elapsed.

But that takes guts because you never can be sure that the market will rise in any given period. What if you had invested your entire fortune in mid-July, just before the market went into a 19 percent nose-dive? Far better to have invested it at the end of August, when the market reached bottom.

Nobody can predict the market’s highs and lows with certainty, so dollar-cost averaging is a sensible alternative for the faint of heart.

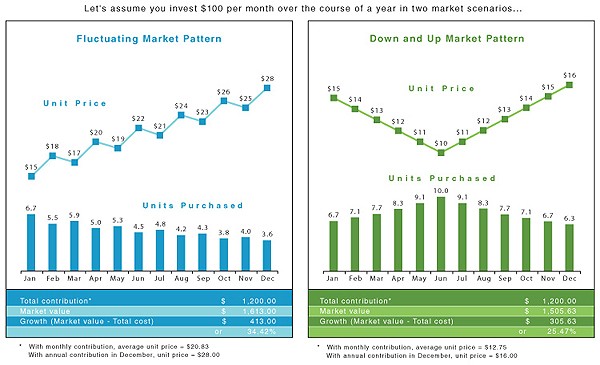

With dollar-cost averaging, you invest equal sums of money in a stock — or group of stocks — at regular intervals over a predetermined period of time. If prices go down, the number of shares you buy goes up. When prices rise, the number of shares you buy goes down.

To take a simple example, suppose you decide to invest $10,000 in XYZ Co. every two months. The first time, the stock is selling for $50 and you buy 200 shares. (We’ll ignore commissions.) The second time, the stock is down to $45 and you buy 222 shares. The last time, the stock is up to $55 and you buy 182 shares. You have accumulated a grand total of 604 shares at an average price of $49.67 per share.

Because you bought more shares when prices were relatively low, your average cost per share was slightly lower than the average cost — $50 — for the three dates on which you bought. That’s all you can reasonably expect, unless you happen to own a crystal ball that really works.

GIFT OF GIVING TO KIDS

Q: It is my understanding that parents may give up to $10,000 per year to each of their children as a nontaxable gift. Is this correct, or are there other limitations or liabilities? Also, is the year a calendar year or a fiscal year? Or do you have to wait at least a full year between gifts?

A: There is indeed a $10,000 annual exclusion, which applies to the sum of all gifts you give each child during a calendar year. If you give a child $10,000 or less during the year, there is no tax liability and no need to file a federal gift-tax form. Each parent can give each child that much each year without incurring a tax liability.

If your child isn’t a minor — in California, a minor is someone under age 18 — you can hand the $10,000 over directly without any tax liability.

If the child is a minor, things become more complicated.

When you give a minor any sum of money directly — above and beyond what the Internal Revenue Service calls normal support — the gift is not tax-exempt. Normal support can include birthday and Christmas presents and other gifts of reasonable size, says IRS spokesman Jesse Weller.

You can avoid a gift tax even when giving money to a minor if you do it through a trust account with a bank or other financial institution, under the terms of the Uniform Trust to Minors Act. The first $10,000 you pay each year into an UTMA account is tax-exempt.

With an UTMA account, you have full control of the way the funds are invested. You also can decide how the money will be spent for the child’s benefit — whether for education. shelter, to buy a car, or whatever. However, you are forbidden to use the money yourself: The gift belongs to the child irrevocably.

ROLLING OVER TO A ROTH

Q: I am almost 72 years old. Last year, as required by tax law, I took the first distribution from my deductible Individual Retirement Account. I’m thinking of converting the balance to a Roth IRA. If I do that, can I avoid taking a distribution this year?

A: Yes. But your question is more complicated than you may realize.

You should think twice before converting to a Roth because this will force you to pay all the taxes owed on your present IRA. If you convert this year, you can spread the taxes out over four years. If you wait until after the New Year to convert, you must pay the taxes all at once.

If you don’t convert and instead stick with your old IRA, you will have to pay taxes on the distributions as you receive them. But you will be able to spread the distributions over more than four years.

A lot depends on which tax bracket you are in now, which bracket you expect to be in during the next four years, and which bracket beyond that.

If your tax rate in the near term will be significantly higher than your anticipated future rate, it probably wouldn’t make sense to convert out of your old IRA. The tax bite would be too high.

Send questions about how to manage your money to moneybag@sfgate.com. or to Arthur M. Louis. Moneybag column, 901 Mission St. San Francisco, Calif. 94103.