Beating the Market with Simplicity and Discipline

Post on: 16 Май, 2015 No Comment

Every other issue of The Validea Hot List newsletter examines in detail one of John Reese’s computerized Guru Strategies. This latest issue looks at the Joel Greenblatt-inspired strategy, which has averaged annual returns of 6.2% since its December 2005 inception vs. 1.7% for the S&P 500. Below is an excerpt from the newsletter, along with several top-scoring stock ideas from the Greenblatt-based investment strategy.

Taken from the March 30, 2012 issue of The Validea Hot List

Guru Spotlight: Joel Greenblatt

Anyone who has ever put cash in the market knows that making money in stocks is hard. But what a lot of investors dont realize is that while it is difficult, it doesnt have to be complicated. You dont need incomprehensible, esoteric formulas and you dont need to spend every waking hour analyzing stocks Joel Greenblatt has proved that.

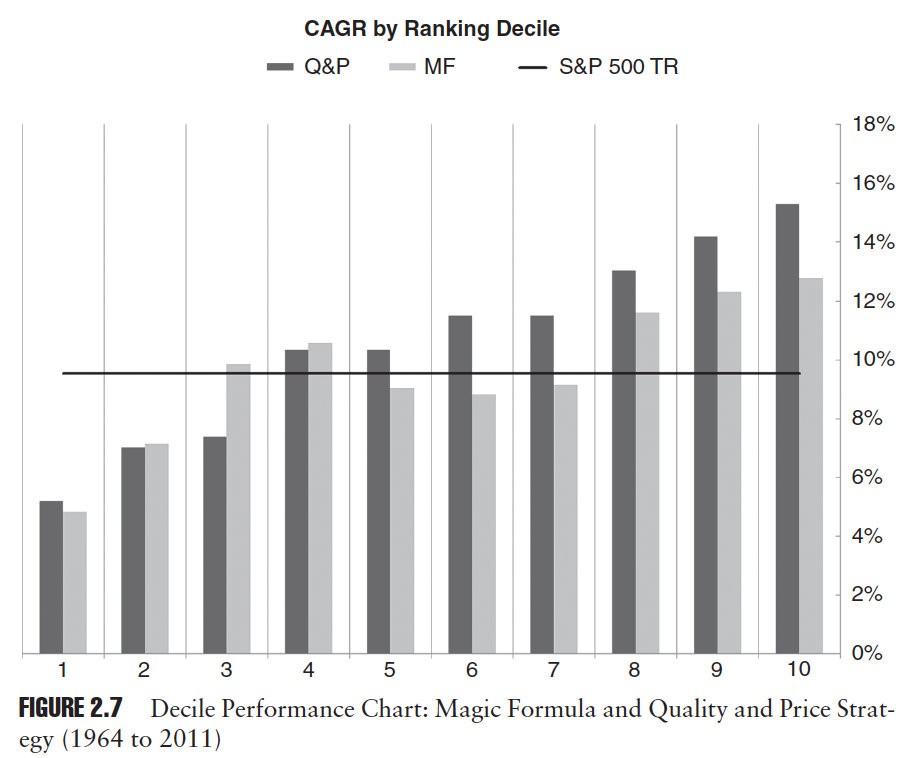

Back in 2005, Greenblatt created a stir in the investment world with the publication of The Little Book that Beats The Market, a concise, easy-to-understand bestseller that showed how investors could produce outstanding long-term returns using his Magic Formula a purely quantitative approach had just two variables: return on capital and earnings yield.

Greenblatts back-testing found that focusing on stocks that rated highly in those areas would have produced a remarkable 30.8 percent return from 1988 through 2004, more than doubling the S&P 500s 12.4 percent return during that period. Greenblatt also posted impressive numbers in his money management experience, with his hedge fund, Gotham Capital, producing returns of 40 percent per year over a span of more than two decades.

Written in an extremely layperson-friendly manner, Greenblatts Little Book its only 176 pages long and small enough to fit in your jacket pocket broke investing down into terms even an elementary schooler could understand. In fact, Greenblatt said he wrote the book as a way to teach his five children how to make money for themselves. Using several simple analogies, he explains a variety of stock market principles. One of these he often returns to involves Jason, a sixth-grade classmate of Greenblatts youngest son who makes a bundle selling gum to fellow students. Greenblatt uses Jasons business as a jumping off point to explain issues like supply, demand, taxation, and rates of return.

In reality, the Magic Formula is less about magic than it is about simple, common sense investment theory. As Greenblatt explains, the two-step formula is designed to buy stock in good companies at bargain prices something that other great value investors, like Warren Buffett, Benjamin Graham, and John Neff also did. The return on capital variable accomplishes the first part of that goal (buying good companies), because it looks at how much profit a firm is generating using its capital. The earnings yield variable, meanwhile, accomplishes the second part of the task buying those good companies stocks on the cheap. The earnings yield is similar to the inverse of the price/earnings ratio; stocks with high earnings yields are taking in a relatively high amount of earnings compared to the price of their stock.

To choose stocks, Greenblatt simply ranked all stocks by return on capital, with the best being number 1, the second number 2, and so forth. Then, he ranked them in the same way by earnings yield. He then added up the two rankings, and invested in the stocks with the lowest combined numerical ranking.

The slightly unconventional ways in which Greenblatt calculates earnings yield and return on capital also involve some good common sense and are particularly interesting given the recent credit crisis. For example, in figuring out the capital part of the return on capital variable and the earnings part of the earnings yield variable, he doesnt use simple earnings; instead, he uses earnings before interest and taxation. The reason: These parts of the equations should see how well a companys underlying business is doing, and taxes and debt payments can obscure that picture.

In addition, in figuring earnings yield, Greenblatt divides EBIT not by the total price of a companys stock, but instead by enterprise value which includes not only the total price of the firms stock, but also its debt. This give the investor an idea of what kind of yield they could expect if buying the entire firm including both its assets and its debts. In the past few months, weve seen how misleading conventionally derived P/E ratios and earnings yields could be, since earnings had been propped up by the use of huge amounts of debt. Greenblatts earnings yield calculation is a way to find stocks that are producing a good earnings yield that isnt contingent on a high debt load.

In my Greenblatt model, I calculate return on capital and earnings yield in the same ways that Greenblatt lays out in his book.

We added the Greenblatt portfolio to our site in January of 2009, but have been tracking its performance internally for several years, and its underlying model has factored into our Hot List selections for the past four years or so. So far, the model has been a strong performer, with some big ups and downs. Since we began tracking our 10-stock Greenblatt-based portfolio in late 2005, the S&P 500 has gained just 11.1%; the Greenblatt-based portfolio has gained about 46% thats 6.2% annualized, vs. 1.7% annualized for the S&P. The portfolio beat the market in 2006 and 2007, and then did what few funds have done: limit losses in what for stocks was a terrible 2008, and handily beat the market in the 2009 rebound. It fell 26.3% in 08 not good, but much better than the S&P 500s 38.5% loss and surged 63.1% in 2009, vs. 23.5% for the S&P. It beat the market slightly in 2010, had a rough 2011 (losing 15.3%), and has lagged so far this year. Greenblatt stresses that the strategy wont beat the market every month or even every year, however, which is important to remember. Over the long haul, though, it should produce excellent returns.

One note: Because of the way financial and utility companies are financed (i.e. with large amounts of debt), Greenblatt excludes them from his screening process, so I do the same. He also doesnt include foreign stocks, so I exclude those from my model as well.

Heres a look at the current holdings of my Greenblatt-based portfolio. Among the holdings are four firms from the much-maligned for-profit education industry, a sign of how the strategy isnt afraid to head into rough waters to find bargains.

Bridgepoint Education Inc. (BPI)

Apollo Group Inc. (APOL)

ITT Educational Services (ESI)

GT Advanced Technologies Inc. (GTAT)

Strayer Education Inc. (STRA)

C&J Energy Services Inc. (CJES)

Iconix Brand Group, Inc. (ICON)

VAALCO Energy, Inc. (EGY)

AmSurg Corp (AMSG)

While Greenblatts methodology is completely quantitative, one of the most important aspects of his approach is psychological and its something that I believe is critical to keep in mind in the current financial climate. To Greenblatt, the hardest part about using the Magic Formula isnt in the specifics of the variables; its having the mental toughness to stick with the strategy, even during bad periods. If the formula worked all the time, everyone would use it, which would eventually cause the stocks it picks to become overpriced and the formula to fail. But because the strategy fails once in a while, many investors bail, allowing those who stick with it to get good stocks at bargain prices. In essence, the strategy works because it doesnt always work a notion that is true for any good strategy.