Agricultural FDI Risky Business

Post on: 19 Июнь, 2015 No Comment

Al-Arabiya reported a few weeks ago that the political crisis in Ukraine and Russia is threatening the availability of food in Egypt and Jordan. Food prices becoming hostage to political crises is certainly not a new phenomenon: food plays an important role in the stability of societies through its availability, affordability, and quality. We learned this lesson from the 1789 French Revolution and more recently, many commentators link soaring food prices in 2010 with the events leading up to the ‘Arab Spring.’ The latter is not surprising when Arab countries import 56% of their cereal consumption, and some Arab countries import 100% of their wheat consumption. These recent market dynamics have led many countries to revisit their food security strategies with an eye to securing food supply.

There is a vigorous debate over the reasons pertaining to the food price increases in 2008, 2010, and 2012. Many highlight the effects of seasonal, short and medium term factors such as weather changes and biofuel-related crop conversions as well as long term factors such as population growth, income growth, and climate change. These price increases in food have enormous effects on people, for example, the 2008 food crisis pushed 105 million people into poverty.

In addition, the increased price volatility triggered by financial speculation on commodities, induced partially by the U.S. Fed’s quantitative easing, makes planning and coping more challenging for developing countries.

Developing countries have had varying policy responses to rising food prices. Among the responses cited by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) are two that concern this blog: Trade-oriented policy responses (releasing food stocks, reducing tariffs and VAT, controlling prices, restricting exports ) and producer-oriented policy responses (that is, production support measures).

Indeed, even relatively recently many food-exporting developing countries have attempted to isolate their domestic food prices from international markets. For example, during the 2008 food crisis, 25 countries banned food exports .

However, banning food exports is hardly an ideal solution since it can hurt the country’s reputation as a reliable trade partner, may contribute to increasing international prices further, and in some instants the poor in the exporting country will be the most affected as in the case in Tanzania .

South-South cooperation is bringing a new ray of hope for global food supply. Cash-rich, food-importing developing countries are attempting to tackle the issue by addressing international trade challenges through acquiring land in food-exporting countries to secure their food supply. For example, Saudi Arabia is counting on its new program, the “King Abdullah’s Initiative for Agricultural Investment Abroad,” where the Saudi private sector is incentivized through interest-free loans to make agricultural investments abroad. Other countries have similar initiatives. The recent surge in FDI into primary and secondary agriculture highlights this trend.

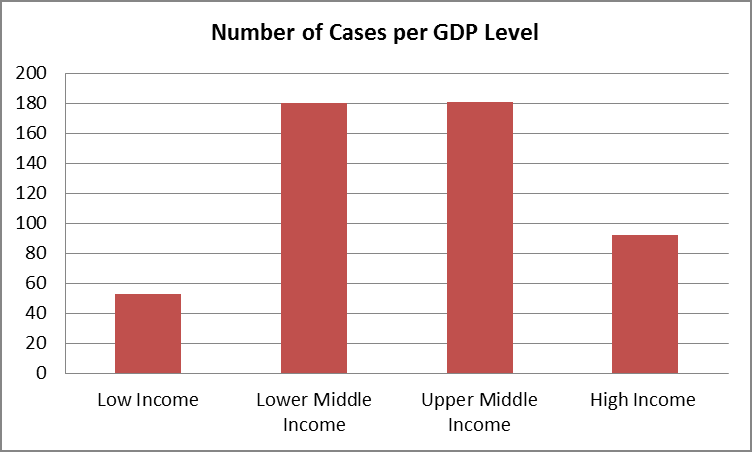

The past few years have witnessed an increase in FDI in the agricultural sector.

20FDI-final-2.jpg /%

Source: World Investment Report 2013, UNCTAD

Yet this approach of acquiring land abroad for agricultural investment contains high levels of risk (political risk in particular) that, paradoxically, may jeopardize food security.

Since the majority of agricultural FDI aims to export outputs, there are several important concerns. Such investments, particularly those which involve large land acquisitions, can be seen as a threat to the host countries by creating concerns over “land grabbing,” food security, and corruption. Under pressure, land acquired in food-exporting countries can become subject to significant risks such as these countries’ policy shifts, export bans, expropriation, breach of contract, and (in extreme cases) civil disturbance. Clearly, then, political risks cloud the environment for this much-needed agricultural investments, as FAO case studies show.

However, given the global challenges the world is facing in food security, it must be acknowledged that FDI into agriculture may offer an adequate solution if appropriately structured. The World Bank Group has been scaling up its efforts to address this. While the World Bank Group shares the concerns on food security, it also recognizes the challenges the issue imposes especially with respect to land governance and agricultural FDI. By engaging all stakeholders, including local communities, the World Bank Group can further enhance the chances of success of these foreign investments for both the investor and host countries.

“Ultimately, the extent to which international land deals seize opportunities and mitigate risks depends on each project’s terms and conditions: how risks are assessed and mitigated…what business models are used (from plantations to contract farming through to various forms of equity participation by local people), how costs and benefits are shared (including the distribution of food produced between home and host countries), and who decides on these issues and how.”

The World Bank has devised standards and guidelines for agriculture investment which include improved governance structures and contractual arrangements with stakeholders. MIGA —the political risk insurance and credit enhancement arm of the World Bank Group—has been active in solid agricultural investments for some time now. The agency plays an important role in making agricultural FDI more effective by reducing investors’ perceived risks to encourage market entry while applying environmental and social performance standards that boost the project’s sustainability.