Active Versus Passive Investing Redefining Alpha and Beta

Post on: 8 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Active versus passive investing is a topic that institutional investors have fiercely debated for many years. While many institutions are focused on whether active or passive management is the optimal solution for the entire portfolio, a more sophisticated approach is appropriate.

Rather than focusing exclusively on one or the other, institutional investors should better understand the nuances of certain active and passive strategies. Doing so can provide an opportunity to use both active and passive as complementary solutions within an institutional investment portfolio.

Active Versus Passive Further Defined

Often, institutional investors define all investment strategies as either actively or passively managed. In reality, however, each of these two strategies can be further defined, which can lead to differences in both expected returns and volatility.

One way in which actively managed strategies can be defined is by the number of holdings: those that are more concentrated versus those that are more diversified. Although there is no magic number that separates concentrated from diversified, concentrated strategies will typically have larger position sizes and a larger weighting in the portfolios 10 largest positions, in addition to fewer holdings, all relative to more diversified strategies. As a result, concentrated actively managed strategies are often thought to exhibit higher conviction because the managers of these strategies are willing to put a larger amount of the portfolio into their best ideas (i.e. highest conviction holdings).

There are also slight nuances within passively managed strategies, most of which involve how the index is constructed. Most indexes weight stocks based on market capitalization, which is the most recent stock price multiplied by the number of shares outstanding; therefore, Stock A, with a market capitalization of $5 million, would have a 5% weighting in an index with a total market capitalization of $100 million (5/100 = 5%). Alternatively, an index might weight stocks based on dividend payments; as a result, Stock A, which pays $1 million in dividends annually, would represent just 2% of an index whose constituents pay $50 million in dividends annually (1/50 = 2%). Passive strategies that track market cap-weighted indexes (i.e. those that are based on price) are typically known as traditional beta, while those tracking indexes that weight components based on factors other than price are commonly referred to as smart beta.

Based on data for exchange-traded funds (ETFs), most of which are passively managed, the number of passive strategies based on indexes that weight securities using measures other than market capitalization (i.e. smart beta) has increased significantly in recent years. According to a recent article in Barrons, today there are more than 1,400 ETFs, tracking more than 1,000 different indexes, while there are at least 20 different approaches to weighting and 27 different selection criteria for indexes tracked by ETFs. A decade ago, all but a few ETFs weighted companies by market cap; however, almost half of ETFs currently on the market today use a different criterion. Therefore, the proliferation of smart beta strategies provides institutional investors with another tool they can use to construct portfolios. In order to utilize each of these strategies properly, however, institutional investors must first understand the differences in expected risk and return for each strategy.

Tracking Error and Alpha: Are They Related?

In order to understand the expected risk and return of each strategy, institutional investors must first understand the relationship between two commonly used statistical measures: tracking error (risk) and alpha (return). Tracking error is a risk statistic that measures the volatility of a portfolios excess returns relative to an index. It is calculated as the standard deviation of excess returns over a period of time, such as the standard deviation of monthly excess returns over a 10-year period. Typically, a traditional beta passive strategy should generate the lowest tracking error, while a concentrated active strategy should result in the highest tracking error. Alpha is a return statistic that measures the excess return generated by an investment above that of an index. Because passive strategies seek to track the performance of an index, only active strategies are thought to generate alpha, which can be either positive or negative.

One of the golden rules of investing is that in order to outperform an index (i.e. provide positive alpha), the portfolio must be different from the index (i.e. generate higher tracking error); therefore, tracking error and alpha are related. Consider the following example to illustrate this concept. Instead of owning all of the stocks in an index, an active manager selects those stocks that it expects to outperform the index. As a result, the manager has structured its portfolio differently than the index, which results in tracking error and ultimately alpha, either positive or negative. In terms of actively managed strategies, those that are more concentrated typically lead to higher tracking error when compared to those that are more diversified; therefore, concentrated strategies also have the ability to generate higher alpha as well. (See Figure 1.)

Because passive strategies track an index, most institutional investors expect them to generate low tracking error and no alpha; however, this is not the case if passive is separated into traditional beta and smart beta. Traditional beta seeks to simply replicate the performance of market cap-weighted indexes, which are those that are most representative of the broad market; therefore, traditional beta strategies typically generate little, if any, tracking error or alpha. On the other hand, smart beta strategies also seek to passively track an index; however, because these types of strategies use a different methodology to weight securities, their returns can differ from those of a market cap-weighted index. As a result, relative to a market cap-weighted index, a smart beta strategy will typically lead to a modest level of tracking error and the opportunity to generate alpha. Therefore, even though smart beta is a passively managed strategy, its weighting methodology can result in alpha, which can be positive or negative. After understanding the nuances between the various types of active and passive strategies, institutional investors can now focus on how each of these strategies can be used within a single portfolio.

Core-Satellite: Combining Active and Passive

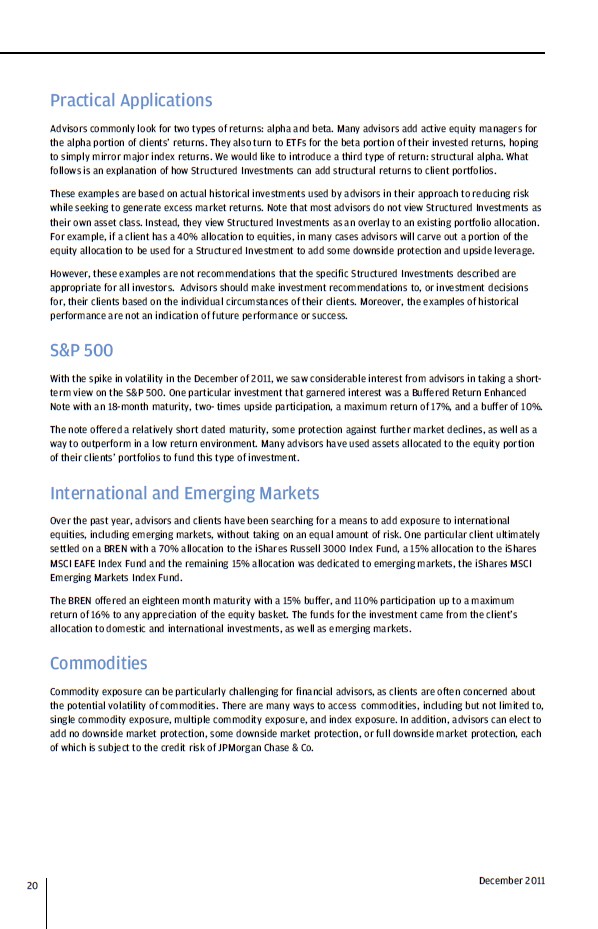

By redefining the concept of active versus passive, institutional investors can use all four strategies within their investment portfolio by implementing a core-satellite approach. Core strategies are typically those that are well diversified and provide broad exposure to an asset class, while satellite strategies complement a core strategy by providing the opportunity to generate alpha.

Traditional beta is typically best used as a core approach because it results in the lowest tracking error and provides the broadest exposure to an asset class. Conversely, concentrated active is used exclusively as a satellite approach because it has the highest amount of tracking error and typically results in the highest alpha as well. Therefore, a combination of the two should result in a market-like return from the traditional beta strategy complemented by the alpha generated by the concentrated active strategy. Smart beta and diversified active strategies can serve as either core or satellite approaches, depending upon the asset class; however, institutional investors should refrain from using traditional beta strategies as a satellite approach or concentrated active strategies as a core approach. This is because traditional beta strategies do not generate the alpha required of a satellite approach and concentrated active strategies do not provide broad exposure to an asset class because they result in too much tracking error.

Rather than broadly defining active and passive, institutional investors would be better served by differentiating diversified from concentrated within the actively managed portion of their portfolio and traditional beta from smart beta within the passive portion. Doing so should allow institutional investors to better understand the risk and return expectations of each strategy, as defined by tracking error and alpha, thereby allowing these different strategies to be used as complementary solutions within an institutional investment portfolio.

This publication has been prepared by Lancaster Pollard Investment Advisory Group. It is for informational purposes and is not an offer to buy or sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any security or instrument or to participate in any particular investment strategy. The information provided is not intended to be a complete analysis of every material fact respecting any strategy and has been presented for educational purposes only. Please contact your investment consultant to discuss your organizations situation. The information herein has been obtained from sources believed to be accurate and reliable; however, we do not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy or completeness of any information and are not responsible for any errors or omissions or for the results obtained from the use of such information. Opinions and data provided in this article are subject to change without notice. Any return expectations provided are not intended as, and must not be regarded as, a representation, warranty or prediction that the investment will achieve any particular rate of return over any particular time period or that investors will not incur losses. There are risks involved with investing, including possible loss of principal.

Adam Smith, CFA, CAIA, is the investment strategist with Lancaster Pollard Investment Advisory Group in Columbus. He can be reached at asmith@lancasterpollard.com .