AAII The American Association of Individual Investors

Post on: 16 Май, 2015 No Comment

by Prem C. Jain, Ph.D. CPA

Few people consistently make money betting on horse races. In finance terms, the horse racing market is efficient. But is the stock market efficient?

Some people argue that the stock market is efficient and that you should not spend any time trying to beat the market averages. On the other hand, others, including Warren Buffett, argue that the market is not efficient. It is not productive to debate whether the market is efficient; the important point is to think about the extent to which it is efficient. We come across many questions in our lives when a simple yes-or-no answer is not very meaningful. When someone asks, Am I going to be able to make a living if I study engineering? or Am I going to get a job if I have a degree in mathematics? the correct answer is generally Yes, of course. However, it is more important to know how good a living you can expect to make if you become an engineer or what kind of job you can land if you get a degree in mathematics. In the same manner, a simple yes or no to the market efficiency question is not worth getting agitated about. It is more important to know how, when, why, and to what extent the market is efficient and, especially, how, when, why, and to what extent it is not efficient.

Can I Make Money in the Stock Market?

Instead of thinking about market efficiency, you should ask, Can I make money in the stock market? Making money in this case means generating above-average returns. My answer to this all-important question is Yes, of course. If I thought otherwise, I would not be writing Buffet Beyond Value , I would not be investing in individual stocks, and I would not be teaching Buffetts ideas. But it is also important to recognize that making money is not effortless. There may be bargains out there, but there is no free lunch.

As a starting point, consider these two simple questions. They should help you start thinking about making money in the stock market and whether you should try to beat the market or whether you are better off investing your money in an index fund.

- Do most professional money managers generate above-average returns in the stock market?

- Do most individual investors generate above-average returns in the stock market?

The answer to both questions is no. It has puzzled me for a long time that most professional money managers cant beat the S&P 500 index. Among those who can, few do it consistently. Roughly speaking, this evidence supports market efficiency. You then need to ask, If most money managers cannot beat the S&P 500 index, how can I?

First of all, since most money managers do not beat the market averages, it should be clear that you should not listen to most money managers. What does it imply about reading the Wall Street Journal and Barrons and watching CNBC? You should read the financial press and watch TV for facts, for events, for news, for analysis, but not for opinions. You should listen to only a select fewsuch as Warren Buffett, John Templeton, and Peter Lynchwho have built a preeminent record over many years. Otherwise, you should tune out when unsolicited advice from talking heads comes your way.

Most Academics Favor Market Efficiency

Most academics promote the efficient market theory as the mantra for investing in the stock market. It does not suggest that intelligent investors can never beat the market. The main reason academics have internalized the efficient market theory is that it builds on appealing assumptions of rationality. But people are often irrational. So, at the very least, be careful in taking academic advice to heart: Use a pinch of salt. Once again, the research findings may be interesting to look at, but you do not have to agree with interpretations that can sometimes be a bit of a stretch, given the evidence. And the academics do not always agree with one another; some new academic research now casts doubt on earlier evidence that the stock market is efficient. In academia, new ideas are always welcome and debated vigorously. In a well-known book, Professors Andrew Lo and A. Craig MacKinlay explained several developments and argued that financial markets are predictable to some degree but far from being specimens of inefficiency or irrationality. It takes convincing evidence from a variety of research findings before new ideas are widely accepted.

Even if the market were efficient, there is still no harm in buying individual stocks using your own knowledge. In an efficient market, you cannot lose money even if you want to. For example, consider a game in which your friend tosses a fair coin, and you randomly call heads or tails. In this game, you will win half the time and lose half the time regardless of what you call. In other words, in a fair game of chance, even if you try to lose your money, you cannot do so consistently. If the stock market is efficient, you cannot, on average, lose money even if you want to. You will incur the cost of trading in terms of brokerage commissions, but as long as you do not trade often, you will do as well as, or better than, most money managers. On the other hand, if the market is not efficient, you can learn from your trades and you may develop the skills necessary to beat the market.

Other evidence in the academic literature suggests that academics still know little about the workings of the stock market. For example, they have not yet come up with a good definition of risk that works well in predicting individual stock returns. One problem with reported beta [a measure of a stocks risk relative to the market] is that it is only an estimate. True beta could be substantially different from the estimated beta in various publications such as Value Line. In academic parlance, the standard deviation around the estimated beta is very large. For example, when the reported beta is 1.0 [meaning that the stock should rise and fall with the market], true beta could easily fall anywhere between 0.5 [stock is 50% less volatile than the market] and 1.5 [stock is 50% more volatile than the market]. And, there is generally no way to tell if an error has been made.

Most evidence in support of market efficiency comes from research that falls into the category of so-called event studies, which are carefully done and present some fascinating findings. They often examine performance of a portfolio of stocks after selected events, such as announcements of earnings and mergers. Many of these studies conclude that after such an announcement is made, it is generally too late for an average investor to invest in that stock. Therein lies the rub. These studies should not be interpreted to imply that you cannot identify stocks that are likely to be good long-term investments in the first place.

Why do prices deviate from fundamentals? This happens when an unusual number of buyers or sellers come to the market in a short time, creating an imbalance. This is a classic example of the effect of supply and demand on prices. For example, consider a situation when you come across many houses for sale in your neighborhood. This can happen by chance alone, with no long-term effect on the housing prices in the neighborhood. Prices will then temporarily fall and will remain low until the number of houses on the market reverts back to normal. The main point here is that there are frequent imbalances in demand and supply that cause prices to deviate from their intrinsic values.

In the stock market, demand and supply seem to fall out of balance frequently. If an influential financial analyst advises his clients to sell a particular stock, the supply of sellers may outpace the supply of buyers. Prices can then fall quickly and may go well below what the fundamentals would suggest. This example can be generalized to include the effect of any news or disclosure of financial information. Some investors react to such disclosures optimistically while others react pessimistically. When one group or the other dominates any particular situation, prices can deviate from the fundamentals. This can also happen for the entire market. In 1987, the so-called portfolio insurance scheme practiced by mutual fund managers required them to sell more and more stocks as prices fell. On October 19, 1987, an initial decline of a few percentage points in the market indexes in the previous few weeks made portfolio managers sell additional stocks, leading the market to decline by 23% in one day. Investors who understood the circumstances benefited from the buying opportunity. In general, individual stocks, rather than the market as a whole, are more likely to afford good investment opportunities because a smaller dollar amount can affect their prices considerably.

Recent Evidence on Market Inefficiency

Many recent academic studies have begun to provide evidence that even within the simple research framework of event studies, the market may not be efficient. Academic researchers are at a loss to explain why, after a good earnings report, a companys stock price continues to move up and similarly, after a bad earnings report, why the stock price continues to move down. This evidence on momentum in prices has also been documented for other events, such as spin-offs and stock splits. The results from other studies show that stocks that have done well in the recent six to 12 months continue to do well during the following six to 12 months. Similarly, the evidence suggests that you should avoid stocks that have been performing poorly in the recent six to 12 months. Evidence also shows that stocks that underperform over a five-year period do well in the following five-year period, and vice versa. After a rigorous examination of the data, Professors Louis Chan, Narasimhan Jegadeesh, and Josef Lakonishok published a study ruling out the possibility that market risk, size, and book-to-market effects can explain momentum in stock prices. They concluded that the results suggest a market that responds only gradually to new information. These results are disturbing to market efficiency advocates but may give you opportunities to earn superior returns in the stock market.

Essentially, it [efficient market theory] said that analyzing stocks was useless because all public information about them was appropriately reflected in their stock prices. In other words, the market always knew everything.

Warren Buffett, Berkshire Hathaway Annual Report 1998

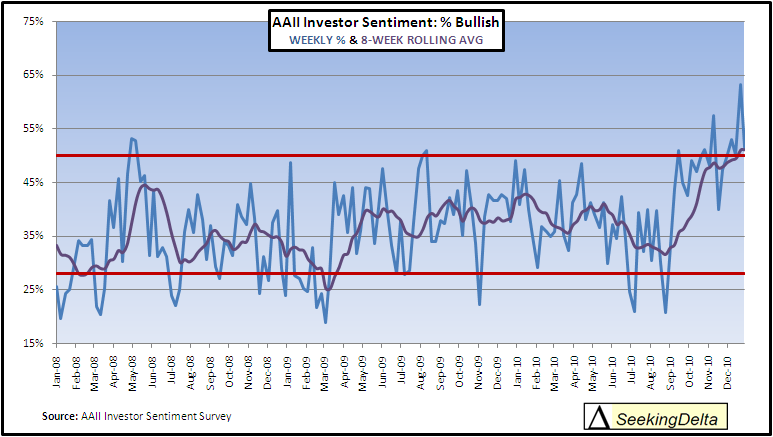

For a critical thinker, it is easy to criticize any evidence, including the evidence on market inefficiency. Some studies find that the market reacts slowly (underreacts) to earnings and other announcements. However, other studies show that the market overreacts to some other types of announcements. This leads to the conjecture that researchers look for patterns in historical data, and given enough computer time, they may conclude that there are patterns where there are none. Essentially, we should be aware that we use hindsight when we conclude something from our research findings. Often, we can conclude things about the past: that the market was undervalued in 1974 or overvalued in 1972, for instance. Without the benefit of hindsight, can we really tell when the market is over- or undervalued? Not really. Putting it another way, there are always enough pundits with bullish and bearish sentiments, and some of them inevitably end up being correct. Overall, inside academia, there is an ongoing lively and healthy debate on the extent to which the markets are efficient and how to measure risk.

The Buffett Viewpoint

Warren Buffett does not say that beating the market is easy. In his discourse on market efficiency in the 1988 Berkshire Hathaway annual report, he concludes, An investor cannot obtain superior profits from stocks by simply committing to a specific investment category or style. He can earn them only by carefully evaluating facts and continuously exercising discipline. Buffett makes three main points about choosing stocks and trying to beat the market.

Get full access to AAII.com, including our market-beating Model Stock Portfolio, currently outperforming the S&P 500 by 4-to-1. Plus 60 stock screens based on the winning strategies of legendary investors like Warren Start your trial now and get immediate access to our market-beating Model Stock Portfolio (beating the S&P 500 4-to-1) plus 60 stock screens based on the strategies of legendary investors like Warren Buffett and Benjamin Graham. PLUS get unbiased investor education with our award-winning AAII Journal. our comprehensive ETF Guide and more – FREE for 30 days

- To beat the market, you must invest only in companies about which you are likely to know more than most participants in the market. It is a basic principle of most games. If you are not better than your opponent, you are probably not going to win very often. Like Buffett, you should focus on one or more industries that appeal to you.

- Buffett has proposed that investors think of making only a limited number of stock market decisions in their lifetime. Once they have made those decisions, they should not be allowed to make any more decisions. If you keep this in mind, you are unlikely to make many mistakes. To cement this thought, think about the effort you expended before you bought a house or a computer, before you decided to attend a particular college or accept a job offer. Because these decisions are not easy to reverse, most people make good decisions. If you think of buying a stock as a similarly long-term commitment, you will make better decisions.

- To beat the market, you must learn to ignore its volatility. It is common for investors to become anxious and sell when stock prices go down or buy when stock prices go up. But when an investor buys a stock for the long run after learning about the company, market volatility will have less of a psychological impact on the investor. Ignorance may make volatility your enemy, but knowledge makes it your friend.

Conclusion

Overall, the stock market can help you make money if you are willing to put in the time and effort to develop the winning mind-set to learn to play the game well. Since most people do not put much effort into it, it is not surprising that most of them do not beat the market averages. For these people, the markets are efficient. For those who are willing to do what is necessary to master the game, even if only in small corners of a single industry, it should be possible to beat the opponent: the market averages.

Prem C. Jain, Ph.D. CPA is the McDonough Professor of Accounting and Finance at the McDonough School of Business, Georgetown University, in Washington D.C..