Will stocks Lost Decade usher in another bull market

Post on: 28 Март, 2015 No Comment

I’ve lost a bet. I’ve lost my keys. But I’ve never lost a decade until now, Sam Stovall, S&P’s chief strategist, quipped in his Lost Decades report.

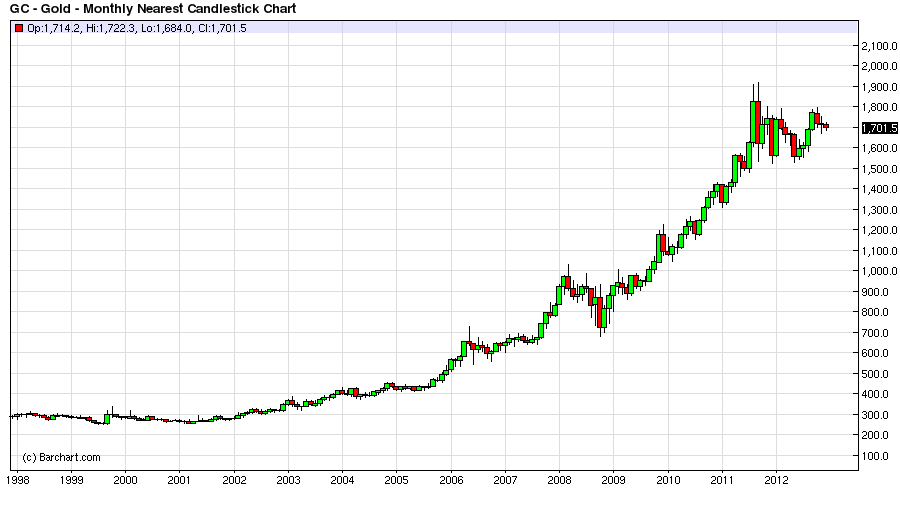

Indeed, a $1 investment in the S&P 500 on Dec. 31, 1999, was worth roughly 90 cents at the end of 2009 and that negative return includes dividend income. In contrast, investments viewed as havens, or more conservative places to park cash, delivered positive returns in the 2000s. A $1 investment in gold grew to nearly $4, according to Strategas Research Partners. And a buck invested in U.S. government bonds, arguably the world’s safest investment, grew to nearly $2.

The dismal showing by U.S. stocks raises a key question on the first trading day of the 2010s: Will the lost decade serve as a bullish launching pad for the new decade? Or will the negative vibes from two brutal bear markets in the past 10 years and the economic damage caused by the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression set the stage for a second decade of subpar performance for U.S. stocks?

In the past, stocks have fared well after 10-year periods in which they fared poorly.

The S&P 500 has never suffered back-to-back losses in calendar decades. In the 1930s, the last decade the index bled red ink, it posted an annualized loss of 5.3%, excluding dividends, and posted a paltry annual total return, which includes dividends, of 1.0%, S&P says.

The good news: The index posted annualized total returns of nearly 9% in the ’40s and 19% in the ’50s.

Similarly, an analysis of the 15 worst rolling 10-year periods for the S&P 500 by The Leuthold Group found that stocks posted positive returns in the next 10 years in all 15 cases. The average annual gain: 10.7%, topping the 10% long-term average.

In general, after bad periods come good periods, says Bob Doll, global chief investment officer of equities at BlackRock.

But not always. Japan’s stock and real estate bubble that burst in early 1990 set Japan up for not one lost decade but two. The Nikkei stock average peaked on Dec. 29, 1989, at 38,915 but remains more than 70% below its high despite big periodic rallies.

Why do long periods of lousy stock returns tend to be followed by long periods of solid returns?

Steep drops wipe out excesses. Jeremy Siegel. a finance professor at the Wharton School of business and author of Stocks for the Long Run. notes that the nearly 20% annualized total returns posted by the S&P 500 in the 1980s and 1990s were the best back-to-back decades ever. The losses that followed in the 2000s were the market’s way of wringing out the euphoria.

The horrible decade has wiped out all the excesses of the previous two decades and put us back on track for more normal returns, Siegel says.

Shocks to investor sentiment are a positive contrarian sign. Jeff Kleintop, chief market strategist at LPL Financial. says stocks tend to get riskier when investor expectations are super-optimistic. On the flip side, when sentiment gets depressed, upside surprises are more likely. Why? Most investors who wanted to get out of the market have done so, paving the way for higher prices and greater demand for stocks when conditions improve.

We began 2000 so optimistic, and valuations were so high, Kleintop says. Now at the start of the 2010s we are very, very pessimistic.

Sharp stock price haircuts create value. After periods in which the broad index goes nowhere, or falls more than 50% as it did in the last bear market, formerly lofty valuations come down sharply, providing cheaper entry points for investors, says Francis Kinniry, a principal at Vanguard’s Investment Strategy Group.

After steep drops, You are buying stocks at fair value or a discount to fair value, he says.

Still, Kinniry, co-author of a Vanguard paper on the lost decade, insists that past results don’t tell investors much about what comes next.

Still, there is credence in the thesis that after long periods of lousy stock performance, the conditions needed for stocks to flourish materialize.

BlackRock’s Doll argues that it is improving business, economic and market fundamentals that eventually drive stock prices higher not just the calendar pages flipping to a new decade.

The world economy will continue to grow, says Doll, ticking off perhaps the biggest reason he and most optimists think stocks will post average annual gains of 6% to 8% in the 2010s.

Doll’s investment thesis revolves around a few key points. The first is that world growth is sustainable. The growth, he says, will increasingly be led by emerging-market economies, such as China, India, Brazil, Russia and other countries benefiting from the emergence of a new middle class with jobs, cash and the willingness to spend.

Also bolstering Doll’s bullish view is the fact that a flourishing global economy will enable U.S. companies to continue growing their profits. He also expects investors who fled the stock market during the scary meltdown in early 2009, and who now have too small a helping of stocks in their portfolios, to ratchet their stock holdings back up.

Vanguard’s Kinniry points to other improving conditions that suggest higher stock prices in the 2010s. He notes that the price of stocks relative to their earnings, known as the P-E ratio, has come down sharply since the 2000 peak of more than 30.

Based on analysts’ expectations for 2010 earnings, the S&P 500 is now trading at 14.5 times earnings, says Thomson Reuters. And that’s a shade below the long-term average of 15. The fact that yields on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds are rising after hitting historic lows last year also suggests that the odds are good that stocks will post better returns than bonds and cash in the coming decade, Kinniry says.

Jim Paulsen, a strategist at Wells Capital Management, says: We are one innovation away from another bull run.

Bears also have their points

But for each bullish point, there is a bearish counterpoint.

One skeptic is Tony Crescenzi, strategist and portfolio manager at Pimco. Pimco coined the phrase the new normal to describe its view of a financial world far less stock friendly than the go-go ’80s and ’90s.

Time, in and of itself, is not a real harbinger of stock prices, and other lost decades were followed by many more years of stagnant returns, Crescenzi says. He notes that the Dow Jones industrials went nowhere between 1964 and 1982, and that after the 1929 crash the Dow didn’t return to its previous high until 1954.

The ultimate drivers of stock prices are corporate profits and the willingness of investors to take the extra risk of owning stocks, Crescenzi says. But he warns that both profitability and risk-taking will be pressured this decade by long-term negative influences caused by the bursting of the credit bubble. The days of growing the economy and profits with the help of cheap, borrowed money are over due to the reduced availability of credit and the reduced appetite for borrowing, Crescenzi says.

Another potential drag on stocks is what Crescenzi refers to as the de-risking mentality. As the Baby Boom generation ages, investors will likely pursue more conservative investment strategies that protect savings from so-called black swan events improbable but high-impact occurrences such as the 2008-2009 mortgage and credit market meltdown.

As a result, stock purchases by individual investors are likely to remain tepid, as has been the case since the tech stock bubble burst in early 2000.

If households did not return (to the stock market) after the shock they received after the bursting of the (tech) bubble in 2000, how can we expect them to return after this latest shock? Crescenzi says.

Axel Merk, president and chief investment officer of Merk Mutual Funds, says fallout from the financial crisis and the unprecedented government intervention to help jump-start the economy will eventually spell trouble for financial markets.

We created a launching pad into an era of instability, Merk says. The great subsidy from the government has propped up the housing market, but makes the recovery highly unstable.

Merk fears the Fed will leave short-term interest rates too low for too long (they are now at a historic low of roughly 0%), causing high inflation that will harm the economy and markets.

Will recent problems linger?

Investors who see much better returns ahead are making the same mistake as those who expect a V-shaped recovery, says Michael Panzner, who writes a blog, Financial Armageddon. and is the author of When Giants Fall: An Economic Roadmap for the End of the American Era .

They fail to grasp that the crisis-led downturn was not a cyclical event, but the first stage of a secular recalibration, he says.

Panzner believes the causes of stocks’ poor performance in the 2000s the bursting of the housing bubble, an economy built on debt and an easy money policy from the nation’s central bank have yet to be resolved.

Stocks, he argues, are still trading far above the single-digit P-Es that have kicked off sustainable bull markets in the past.

Panzner’s biggest worry is a hostile interest rate environment. The need for governments here and abroad to borrow trillions of dollars to fund deficits will push rates sharply higher. The higher rates will inflict a lot of damage on the still vulnerable real estate sector and corporate bottom lines, he says.

Still, history is on Wall Street’s side, says Michael Farr, manager of the Touchstone Capital Appreciation fund: While nobody can say with any certainty what stocks will do going forward, returns following these rare periods of underperformance have been excellent. It is not unreasonable to expect long-term stock returns of 7% to 8%.