Why equity investment during bad times yields good results Economic Times

Post on: 30 Апрель, 2015 No Comment

Prashant Jain

Every investor would like to buy low and sell high. However, the reality for a typical equity investor involves buying high as the market rises, buying less when it falls, and not buying anything when the market is really down.

When the Sensex was at 3,049 and the average forward price to earning (PE) ratio of the benchmark was 10.34 in March 2003, investors kept away from equities.

The total investment in equity funds during 2002-3 was Rs 118 crore. However, when the average PE was high at 20.56, more than Rs 52,000 crore was invested in equity funds in 2007-8.

More specifically, between October 2007 and March 2008, when the Sensex was near 20,000, the net sale of equity mutual funds was worth Rs 41,142 crore. On the other hand, just a year later, between October 2008 and March 2009, when the Sensex was below 10,000, the sale of equity funds was a negative Rs 162 crore. In the past four years (2008-9 to 2011-12), even though the markets have been down and the PE is lower, the cumulative inflow in equity funds has been a negative Rs 6,000 crore.

This is not the first time that such a thing has happened. Between 1988 and 1992, after the Sensex went up a staggering 10 times from 400 to 4,000 level and the forward PE reached an all-time high of 40 times, an equity new fund offer collected nearly Rs 4,000 crore (Rs 20,000 crore at today’s prices). Similarly, during the IT boom, billions of rupees were invested in IT, not to forget a similar trend in real estate and related sectors during 2007.

This pattern, wherein an overwhelming majority of investors mistimes the market repeatedly and consistently, is the prime reason for their unsatisfactory experience with equity and for the poor equity ownership in India. While there can be many reasons for this collective mistiming, the key one probably is that most of the investments in equity are not done with a long-term view.

This, despite the fact that the best that equity has to offer is only over long periods. This is unfortunate since investors are not benefiting from the compounding potential of equities by investing for the short term.

At 15% CAGR, Rs 10,000 becomes nearly Rs 20,000 in five years, Rs 50,000 in 11 years, Rs 1 lakh in 17 years, and Rs 2 lakh in 22 years. Due to the erroneous understanding of equities, investors target only small gains over short periods. As the horizon is short term, the entire focus is on guessing the near-term market movements.

This inevitably leads to extrapolating the markets in either direction and, therefore, in a rising market, the expectation is that it will continue to rise. The greed of quick returns leads to higher inflows in equities, and as the trend sustains, both the confidence and greed keep increasing, leading to higher inflows.

On the other hand, in a market that is moving downwards, the expectation is that it will keep moving lower, leading to lesser inflows; the lower the market moves, or the longer the market does not move, the higher is the confidence that it will fall further or that it is going nowhere, resulting in the drying up of fresh investments or redemption of existing investments.

Also, when the market is rising, the news flow is generally good, and vice versa. Therefore, generally, in a rising market, the perceived risk is low even though the actual risk is higher since the valuations are high. On the other hand, in adverse times, when the market is not doing well and the news flow is not good, the perceived risk is high, whereas the actual risk is lower as the valuations are attractive.

The net result is that, time and again, people end up investing large amounts at high valuations and small amounts at low valuations. Clearly, such an approach is not conducive to generating good returns and is likely to lead to disappointing results.

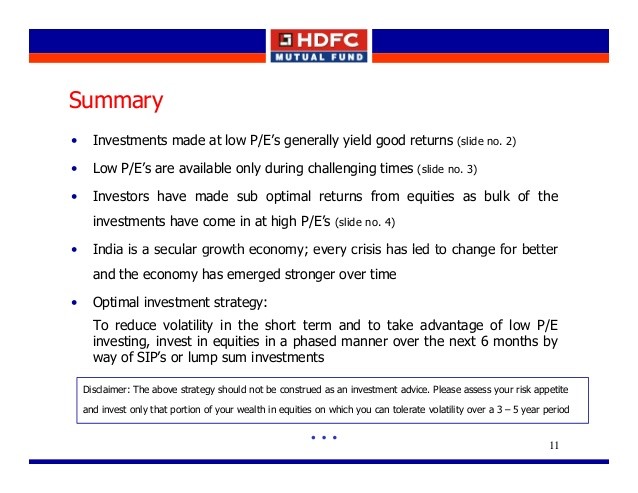

Good returns seldom come from investments made during good times. Instead, they typically come from investments made in adverse times. When the stock market is doing well, companies usually trade above their fair values. It is during adverse times that they trade below their fair values.

In the long run, markets do not remain either overvalued or undervalued; they move closer to the fair value. This is why investments made during difficult times usually give above-average returns, and vice versa.

(The author is executive director and chief investment officer of HDFC Mutual Fund.)