Why Employ a Corporate Trustee The Costs and Benefits of Using an Institution to Trustee Your

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Why Employ a Corporate Trustee. The Costs and Benefits of Using an Institution to Trustee Your Qualified Retirement Plan

Schultz Collins Lawson Young & Chambers

Independent Investment Counsel

650 California Street, 12th Floor San Francisco, California 94108-2716

Telephone (415) 291-3000 Facsimile (415) 421-0737

When the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) was passed, Congress intended to ensure that a qualified retirement plan’s assets would be used only to pay benefits to participants and beneficiaries and reasonable plan operating expenses.

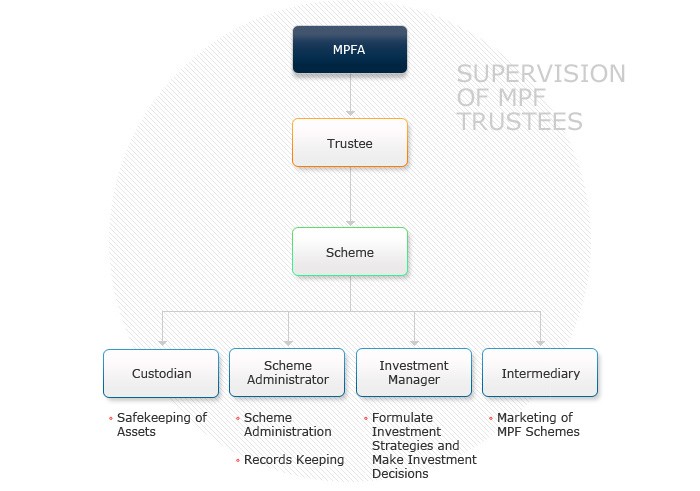

Therefore, ERISA required that all qualified retirement plan assets be held in a trust, and managed by trustees. Trustees have complete control over plan assets held in the trust, although the trust investment decisions may be made by the plan’s administrative committee or by designated investment managers. To the extent that investments are directed, trustees are not liable for investment decisions; however, if trustees choose investments, they will be held to the same standards as any other investment manager.

ERISA also lists the duties of the individuals responsible for setting investment policy and for controlling and managing plan assets: the fiduciaries. A fiduciary must be named in the plan document. Any person with discretion to manage and invest the plan’s assets is also a fiduciary. A plan may have more than one fiduciary.

A plan fiduciary must act solely in the interest of plan participants and beneficiaries, for the exclusive purpose of providing benefits while defraying reasonable plan expenses. Fiduciaries also must:

- Act prudently, using the care and skill that an expert would under similar circumstances;

- Diversify plan investments to minimize large losses, unless it is clearly prudent not to do so; and

- Act according to the plan document, as long as it is consistent with ERISA.

Each plan must have at least one named fiduciary who serves as plan administrator, and at least one trustee. ERISA provides that the written plan document must include one or more named fiduciaries who control and manage the plan’s operation and administration.

In addition to the named fiduciary, a person who performs certain plan management functions is treated as a plan fiduciary. These functions include:

- Exercising any discretionary authority or control in managing the plan or in acquiring or selling plan assets;

- Rendering investment advice for a fee or other compensation, direct or indirect, with respect to any money or other plan property; or

- Acting with discretionary authority or responsibility in plan administration.

Identifying plan fiduciaries is very important: a fiduciary is personally liable for any losses sustained by a plan due to a breach of the fiduciary’s or co-fiduciary’s duty. A fiduciary also must restore to the plan any profits earned by using plan assets for personal gain.

Job titles generally are irrelevant in determining whether an individual is a fiduciary by function. Only individuals with discretionary authority over plan assets or plan management are fiduciaries. Individuals who have no power to make any decisions on plan policy, interpretations, practices or procedures, but who perform administrative functions for the plan are not fiduciaries.

While a plan must identify the named fiduciary, the plan may provide that:

- Any person may serve in more than one fiduciary capacity;

- A named fiduciary, or a fiduciary designated by the named fiduciary, may employ advisers; and

- A named fiduciary may appoint an investment manager to manage, acquire, and sell any plan assets.

Assets of ERISA plans are generally held in trust and managed by trustees either named in the trust instrument or appointed by the plan’s named fiduciary. Trustees have exclusive authority to manage and control plan assets, except when a plan expressly provides that:

- The trustees are subject to the direction of the named fiduciary, or

- The authority is delegated to investment managers.

Trustees subject to the direction of the named fiduciary are called directed trustees. Directed trustees will not be liable for following the instructions of the named fiduciaries. Where plan assets are held in more than one trust, trustees are liable only for the assets in their own trusts. However, where two or more trustees govern one trust, trustees share co- trustee responsibility and each trustee must use reasonable care to prevent the other trustees from breaching their duties.

The responsibility for plan investments cannot be delegated by plan trustees, except where the trustees retain an investment manager, which acknowledges its ERISA fiduciary status and responsibility in writing. An investment manager is defined under ERISA as any fiduciary (other than a trustee or named fiduciary) who:

- Has the power to manage, buy, or sell any plan asset;

- Is registered as an investment advisor under the Investment Advisors Act of 1940, is a bank, or an insurance company licensed to do business in more than one state; and

- Has acknowledged in writing that it is a fiduciary with respect to the plan.

When such an investment manager is hired by the plan, the plan trustees and fiduciaries are relieved of their fiduciary responsibilities for the assets allocated to that investment manager as long as the fiduciaries:

- Are prudent in their selection of manager by investigating the investment manager’s background, experience with investment for similarly sized plans, reputation, credentials (such as registration with the Securities and Exchange Commission), past performance with similar investments, fee structure compared with other investment managers, and the type and frequency of reports to trustees;

- Establish prudent guidelines on investments, with limits on risk, allocation, types of investments, and expected rates of return; and

- Monitor the investment manager on a regular basis to ensure the guidelines are being followed.

Investment advisors to plans are fiduciaries if they:

- Advise on the value of securities or other property;

- Recommend the advisability of investing in, purchasing, or selling securities or other property; or

- Have discretionary authority or control to purchase or sell securities and other property, or agree to offer advice on a regular basis relating to a plan’s investment strategy, portfolio, or diversification.

When a trustee invests funds with an investment company registered under the Investment Company Act of 1940 (i.e. a mutual fund), the mutual fund company is not a fiduciary merely because it holds plan assets for investment.

Frequently, qualified retirement plan sponsors question whether having a corporate trustee makes sense from a cost/benefit perspective. Most corporate trustees act as directed trustees, so other fiduciaries bear responsibility for the investment decisions. In a casual review, it may appear that the trustee’s primary responsibility is merely to act as a glorified cashier, receiving and disbursing funds according to the plan administrative committee’s direction. In most qualified plans, assets are custodied through a mutual fund company, insurance company or stock broker, further limiting the trustee’s role. Consequently, many plan sponsors believe that it makes sense to self-trustee the plan, and save the trustee fee.

Having a corporate trustee adds value to the plan in several ways that are not immediately obvious to the casual observer, including:

- fiduciary responsibility is distributed more broadly, reducing the possibilities for potential conflicts of interest;

- time consuming administrative functions, including preparing consolidated asset and income statements, processing receipts and disbursements, and preparing and filing tax forms, are delegated to an institution specializing in providing these services;

- the trustee role is delegated to an institution specializing in providing trust services, minimizing the possibility that a trust responsibility could be overlooked, thereby exposing the plan sponsor to penalties, or even jeopardizing the plan’s tax-qualified status;

- plans with over one hundred participants subject to the plan audit requirement may pay a lower audit fee for an institutionally trusteed plan, because the plan may be eligible to file a limited scope audit report, and because the institution generally prepares standardized auditor’s reports designed to simplify the audit process;

- since assets are controlled by a corporate trustee, plan participants receive an extra degree of protection that plan assets will be used solely to pay benefits to participants and beneficiaries, and reasonable plan expenses.

For the smaller company, where a company owner or senior executive is often willing to act as a trustee, a self-trusteed arrangement has significant appeal. However, the corporate trustee provides an invaluable buffer between the plan sponsor and the plan assets, while performing a variety of complex and time consuming administrative functions. Consider the following hypothetical situations:

An employee in a small company, where the owner also acts as trustee for the profit sharing plan, is terminated for cause after four years with the company. The profit sharing plan administrator advises the trustee that no plan benefits are due to the terminated employee, because the plan has a cliff vesting schedule, where no benefits are payable to participants with less than five years of service. However, the terminated employee believes that the owner was responsible for their termination, and is now acting in a discriminatory manner, by withholding retirement benefits that would normally be paid.

A company is having difficulty paying its bills, and employees are whispering that the company is facing bankruptcy. The company offers a 401(k) program, and the owner acts as the plan trustee. Employees stop contributing to the program because they fear that their salary deferrals may be used for corporate purposes by the plan.

The owner of a small public company is also the trustee of the company’s Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP). The ESOP controls 20% of the company’s stock. A larger company recently initiated a hostile takeover bid for the company, at a significant premium to the current stock price and has announced that if the bid is successful, they intend to lay off employees and relocate the company. Should the owner/trustee agree to sell shares held by the ESOP to the other company?

In smaller companies, by virtue of the corporate structure, the same individual may be required to act in several capacities at the same time. With respect to a qualified retirement plan, an individual might be:

- the plan sponsor, due to their ownership interest in the company;

- the plan administrator, due to their role as the organization’s senior executive, responsible for making decisions regarding the plan structure, funding, employee eligibility, and other management functions; and

- the participant with the largest account balance in the plan.

In these circumstances, it will be extremely difficult for the individual to fulfill both a plan sponsor and a fiduciary role, acting only in the best interests of participants and beneficiaries when acting as plan administrator, but acting in the best interests of the company when acting as plan sponsor. To expect this individual to also function effectively as the plan trustee is probably unreasonable. Even if the individual were able to distinguish between each separate role, it is unlikely that other plan participants would perceive these separate roles.

The trustee must issue, at least annually, a consolidated statement of trust assets, and a consolidated statement of trust income and expenses, including all:

- employee and employer contributions;

- benefit distributions;

- earnings from investments;

- realized and unrealized gains and losses; and

- plan expenses paid from the trust.

Generally, in a self-trusteed arrangement this responsibility is delegated to a brokerage firm, insurance company or mutual fund. However, final responsibility for the completeness and accuracy of the trust statement remains with the trustee, even though the statement was prepared by another organization.

The trustee is responsible for appropriate handling of all plan receipts and disbursements. These may include:

- receiving, validating and depositing rollover contributions from other employer’s plans;

- approving, signing and distributing participant benefit checks;

- processing regular company and employee contributions;

- processing participant loans and loan payments; and

- approving and processing payment of plan expenses.

Although none of these functions is particularly difficult, handling a high volume of transaction activity can be time consuming for the self-trustee. Further, many of these transactions can be quite time sensitive. Depending on the trustee’s schedule (business trips, vacations, etc.), transactions may be delayed pending the trustee’s availability. Although plans can be structured such that most transaction processing responsibility is delegated to a brokerage firm, insurance company or mutual fund, the trustee retains final responsibility for the accurate processing of trust transactions, even though the transactions were processed by another organization.

One of the primary benefits of a corporate trustee is that as the payor of plan distributions, they are responsible for withholding federal and state taxes, filing appropriate tax reports with IRS and state tax agencies, and reporting tax information to plan participants receiving payments. Generally, the employer or plan administrator would be responsible for preparation of tax reports for designated distributions (taxable plan benefits subject to tax withholding) made by the plan, however this responsibility may be assumed by a corporate trustee when they are responsible for paying plan benefits. Additionally, the corporate trustee can be required to maintain appropriate records regarding the tax filings.

The primary reporting for plan distributions is made on Form 1099-R. This form must be filed with the IRS and a copy must be sent to plan participants and beneficiaries.

Copies of Form 1099-R must be sent to payees by January 31 of the year following the calendar year in which the designated distributions were made.

Copy A of Form 1099-R must be filed with the IRS by February 28 along with transmittal Form 1096 (for Form 1099-R).

Form 1099-R filers are required to maintain certain information relevant to designated distributions. These recordkeeping requirements will be met if the information contained in Form 1099-R is kept, along with certain other information, including the payee’s birth date, plan name and commencement date, plan administrator’s name, and amount and frequency of payments. The IRS may assess penalties for failure to maintain the required information.

Payors of plan payments from which tax was withheld and deposited must file annually Form 945 (Annual Return of Withheld Federal Income Tax). The form is due by January 31 each year.

All income tax withholding reported on Form 1099-R must be reported on Form 945.

Generally, income tax withheld from plan payments must be deposited with an authorized financial institution or a Federal Reserve bank or branch. A Federal tax deposit form must be included with each deposit. FTD revised Form 8109 (in coupon book form) is to be used for this purpose by Form 945 filers reporting income tax withheld.

Many states, including California and Oregon, have similar tax withholding and reporting requirements. State tax law generally applies based on applicable law of the state where the benefit payment was received, not on the law of the state where the payment was made; consequently a company with operations in a single state could have plan withholding and reporting responsibilities in many states, if terminating employees relocate on separation from service. A full discussion of state withholding and reporting requirements is beyond the scope of this paper.

Qualified retirement plans operate under significant legal and administrative constraints. A plan trustee should be familiar with rules of conduct for retirement plan trusts found under:

- the Internal Revenue Code;

- IRS regulations;

- the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA);

- Department of Labor regulations; and

- general trust law.

Given the myriad variety of rules and regulations, it is virtually impossible for an individual to be aware of all applicable requirements. However, even inadvertent violation of a rule could result in significant penalties for the plan sponsor, or disqualification of the trust. Generally, corporate trustees are less likely to inadvertently violate a trust rule, because they regularly work with qualified retirement plans.

Plans covering 100 or more participants must engage an accountant to examine and prepare a report on the financial statements and schedules required to be included in the annual plan tax return (Form 5500)..

The accountant’s examination must be conducted in accordance with generally accepted auditing standards, and must designate any auditing procedures deemed necessary which have been omitted and the reasons for their omission.

The accountant’s report must express an opinion as to:

- The financial statements and schedules covered by the report;

- The accounting principles and practices reflected therein, and

- The consistency of application of the accounting principles with that of the preceding year, and any changes in principles which have a material effect on the financial statements

If plan assets are held through a corporate trustee which is independently audited, the accountant may issue a limited scope audit opinion. This means that the accountant has partially relied on the report of corporate trustee’s independent auditors in considering the trust’s internal controls and procedures. Generally, a limited scope audit is less costly and easier to prepare than a full scope audit.

Further, corporate trustees generally issue professionally formatted asset summaries, income statements and transaction records designed to facilitate the annual audit. Consequently, accountants often charge lower fees for plans with corporate trustees, even when the limited scope opinion is not desired or is not permitted.

Determining the reasonableness of a corporate trustee’s fee schedule can be a complicated task, since there are numerous methods for pricing trust services. Some of the major obstacles to reasonable comparisons include:

- different fee schedules for proprietary investments (i.e. investment products offered by the trust company or an affiliate) and for non- proprietary investments;

- additional investment transaction processing fees (i.e. fees for processing purchases or sales of plan investments). These fees may be especially significant for daily valued participant directed investment plans, which may have investment purchases and sales every day;

- variations in levels of service between corporate trustees; and

- differing levels of flexibility for services that may be provided, and investments that may be offered.

Nonetheless, by making some simplifying assumptions, and by expressing aggregate trust fees in terms of basis points (hundredths of a percent of trust assets), we can develop some rules of thumb for assessing the reasonableness of a corporate trustee’s fees.

Our simplifying assumptions are as follows:

- trustees are classified into three categories:

- captive (trustees solely permitting plans to invest in a narrow range of investment products offered by the trust company or one of its affiliates),

- subsidized (trustees permitting plans to invest in both investment products offered by the trust company, its affiliates, and unaffiliated organizations subsidizing the trust company and unaffiliated and unsubsidized investment products); and

- unsubsidized (trustees permitting plans to invest in totally unaffiliated and unsubsidized investment products).

Generally, captive trust companies are an adjunct service for bundled recordkeeping and investment service providers, and offer little additional service relative to the bundled arrangement without trust services (e.g. if the bundled provider offers tax reporting and filing services, these services are offered whether or not the captive trust company acts as trustee). Consequently, the primary incremental value of the captive trust company stems from the distribution of fiduciary liability afforded by a corporate trustee, and the potential for limited scope audit opinions.

Captive trust companies generally charge a flat annual fee for being named as plan trustee, and issuing certain trust reports. The flat fee is typically $500 to $2,000 per year.

Generally, subsidized trust companies are operated by financial services companies that offer investment management or brokerage services. Usually, the financial services company will also offer its investment management or brokerage services to plan sponsors without involving its trust company; however, when the trust company is not involved with a plan, most of the administrative services typically associated with corporate trustees will not be available to the plan (investment only arrangements).

Trust service fees are generally subsidized by investment management fees, and/or revenue sharing arrangements with unaffiliated mutual fund companies or other entities, and consequently are generally lower than. unsubsidized trustee fees. For example, the Charles Schwab Trust Company (an affiliate of the Charles Schwab Corporation) offers discounted trustee fees for plans investing in certain funds, such as the Schwab 1000 mutual fund (Schwab receives investment management fees from this fund) or the Janus Fund (Schwab maintains a revenue sharing arrangement with this fund).

Subsidized trust companies also permit investments in funds that do not subsidize trustee fees. Generally, fees for these types of investments are at or above market rates, to encourage use of the subsidized funds.

Most subsidized trust companies have a minimum annual fee of between $1,500 and $3,000.

A typical subsidized trust company fee schedule is as follows: