What Exactly Are 12b1 Fees Anyway

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Regulators fret that too many investors don’t understand what they’re paying. Here’s where your dollars are going.

Journal Report

So will this be the year the regulators take action on 12b-1s?

SEC Chairman Mary Schapiro has made clear that’s her intent, and she has asked the agency’s staff for a proposal on 12b-1s this year. We need to critically rethink how 12b-1 fees are used and whether they remain appropriate, she said in a speech in May.

But there’s also a long history of SEC officials talking about overhauling or at least better disclosing 12b-1 fees, followed by no action. Sweeping change could be complex because these fees—often 0.25% of assets a year, but sometimes as much as 1%—are deeply woven into the intricate system for distributing funds to individual investors. Some in the fund industry also say there isn’t any fundamental problem that needs to be fixed.

In most cases, 12b-1 charges (which are named for the 1980 SEC rule that authorized them) are used to pay the companies and individuals through which investors buy fund shares. So investors are paying those agents indirectly, through charges that reduce their funds’ returns.

ENLARGE

Richard Borge

For instance, many do-it-yourself investors use discount-brokerage fund supermarkets to buy and sell funds from hundreds of companies without any transaction fees. But that doesn’t mean supermarket operators, including Charles Schwab Corp. and Fidelity Investments, aren’t getting paid. When an investor holds shares of a fund on one of those firms’ no transaction fee platforms, the fund and/or its manager typically must pay 0.4% of the value of those shares to the firm each year. Many of the funds, in turn, charge investors a 0.25% 12b-1 fee to partially cover that cost. (Why not the full 0.4%? Because a fund can have a 12b-1 charge of up to 0.25% and still call itself a no-load, or no-commission, fund.)

When funds are sold through full-service brokerage firms, fund companies often charge investors a 0.25% 12b-1 fee and use the proceeds to make payments to the brokerage firm for its services and to individual advisers at the firm for their continuing assistance to investors. That 12b-1 fee can be in addition to a front-end load. Issuers of some fund shares, usually identified as Class C shares, compensate the selling company and broker solely through a high 12b-1 fee, often 1%.

In some 401(k) plans, 12b-1 fees are used to make payments that help cover the plans’ administrative costs.

How can I find out the charges and uses at my funds?

Check the expense table in the fund prospectus for the existence and magnitude of a 12b-1. There’s usually some further information in the prospectus or the separate Statement of Additional Information on where the dollars go.

Overall, about 70% of funds have at least one share class with a 12b-1 fee, according to the Investment Company Institute trade group. A few fund companies, including Vanguard Group and T. Rowe Price Group Inc. don’t generally have 12b-1 charges on their funds for direct purchase by individual investors; as a result, investors who buy these funds at other companies’ fund supermarkets must generally pay transaction fees to do so.

Are there advantages in having these expenses paid out of fund assets?

Many in the fund industry say it’s simpler for the funds to pay these charges in bulk. It’s also more tax-efficient for investors. Paying this way can reduce investors’ taxable income from their funds. If they paid separately, many people wouldn’t be able to deduct the expenses on their tax returns.

A more cynical answer is that fund sponsors and securities firms prefer to charge investors in ways that attract little if any scrutiny. One reason fund firms started using 12b-1 charges to replace front-end loads was that investors hated seeing large sums deducted from each fund purchase to pay an adviser.

Are there disadvantages in paying these expenses through 12b-1 charges?

Smart shoppers weigh benefits against costs; if investors don’t realize how much they are paying their financial firms and advisers through this indirect route, they may not be carefully considering whether the services they get are worth what they are paying.

At fund supermarkets, investors making large, long-term purchases could pay less over time by paying transaction fees to buy and sell funds that have lower annual expenses because they don’t have 12b-1 charges.

More fundamentally, there’s a potential conflict of interest when current fund shareholders bear expenses intended to boost sales, which is how 12b-1s were initially envisioned. The fund’s management firm, whose fee is a percentage of fund assets, clearly benefits if the fund grows—but existing investors may not benefit.

When the SEC first allowed such spending in 1980, the fund industry had just gone through a long period of investor redemptions. Because of the conflict concerns, the SEC required fund directors to annually approve a fund’s 12b-1 plan. Many fund directors hate the current system, because they are asked to bless these fee arrangements but have no power to negotiate the outside firms’ charges.

What’s the prognosis for SEC action?

Adjustments are more likely than a repeal of Rule 12b-1, which would force these various charges out of funds’ expense ratios. Andrew Donohue, director of the SEC’s Division of Investment Management, says one approach under consideration by the SEC would treat any 12b-1 charges above 0.25% of assets as a load that is paid over time; since there are rules capping sales commissions, C shares would have to convert after some number of years to shares with no more than a 0.25% 12b-1. That’s the approach the American Funds complex uses now. A proposal from the SEC staff is also likely to require clearer disclosure of the common 0.25% 12b-1s and is expected to spell out updated responsibilities and rules for fund directors weighing 12b-1 plans.

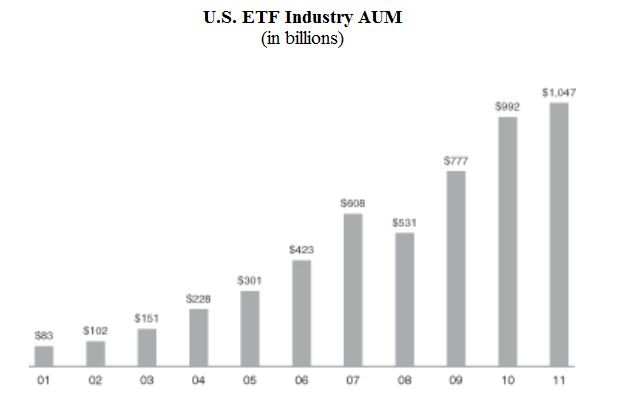

Ironically, over the many years that a 12b-1 overhaul has been discussed but never enacted, some concerns have become less pressing. Sales of fund share classes that rely on high 12b-1 fees to compensate advisers have fallen sharply. More advisers are charging investors clearly disclosed fees for their services, rather than collecting commissions that are built into fund shares. Some advisers who charge fees favor institutional share classes that don’t include 12b-1 fees. Finally, many investors and advisers are choosing exchange-traded funds, which generally don’t have 12b-1 fees and thus usually require the payment of a brokerage commission or a fee to an adviser.