Understanding Taxes

Post on: 5 Июль, 2015 No Comment

1. How are dividends taxed? Are they all taxed the same?

That really depends on the dividends that you are talking about. The annual 1099-DIV form that your company will send you shows how much you received in dividend payments, even if it all went to buy more stock. Report all dividends as income on your annual tax return. The dividends are treated as ordinary income and will be taxed at your marginal tax rate. Pretty simple. It’s much like reporting interest from a savings account — a one line entry. You report the dividends you receive on Schedule B, which is used to record interest and dividend income, but only if you receive more than $400 worth in one year. Otherwise, you simply report dividend income on your main 1040 tax form.

Sometimes capital gains can appear where you least expect them, like on a dividend statement related to a stock or mutual fund that you own. It’s good to look closely at the 1099-DIV forms you receive to see if they say anything like Capital Gains Distribution on them.

Most stock dividends are treated as normal, or ordinary, dividends and don’t count as capital gains — and should be reported directly on Schedule B. If your portfolio is pretty much all stocks and no mutual fund shares, this section is unlikely to apply to you. But let’s review it, just in case.

If you see a Capital Gains Distribution mention on a 1099-DIV statement that you receive, report those distributions directly on Schedule D. Just a few years ago, those distributions were required to first be reported on Schedule B (Interest and Dividends). But no longer. Take your capital gains distributions directly to Schedule D (Capital Gains and Losses).

Be aware that some companies don’t send you the form 1099-DIV when the dividend payments that you received for the year amounted to less than $10. The dividends are still taxable, however. Your year-end account statement will show the total amount of dividends that you received. You should report that number as income, just as if you’d received a 1099-DIV.

If you reinvest your dividends, either in mutual funds or dividend reinvestment plans, things are just a little bit trickier. You still pay tax on the dividends that are distributed to you, and the shares purchased with dividends are accounted for exactly as if you had bought them with money sitting in your bank account. So you must keep the statements showing your cost basis on dividend reinvestment-acquired shares just as you do when you make optional cash payments to buy shares. When it comes time to sell, you need to know the cost basis for all of your shares — those bought with reinvested dividends and those bought separately with your hard-earned money.

Finally, one brief word about credit union dividends: Be careful if you receive a statement of dividends paid to you by your credit union. What some credit unions call dividend income is really interest. So even if it says dividend, treat it as interest and include it with interest income.

Money market mutual funds may be a little confusing, as they can generate both interest income and dividend income. You’ll need to pay attention to the statements they send you. Income reported to you on a 1099-INT is interest income and on a 1099-DIV is dividend income.

2. What are the tax consequences of reinvesting my dividends, if any?

Again, the answer really depends on what dividends you are really reinvesting. When you say reinvestment, most people immediately think of mutual funds. So let’s look at those first.

If you reinvest your dividends within a mutual fund, you are really buying more shares of stock, at different times, and at different prices. You are simply eliminating the middle man: Instead of the mutual fund company sending you a dividend check, and then you sending the mutual fund company that same check to purchase more shares, the mutual fund company just purchases the new shares directly. But make no mistake — these are brand spankin’ new shares that you have purchased. You still need to pay tax on the dividends paid to you, and you also need to update your tax basis in your mutual fund in order to account for these additional purchases of shares.

If you’re not updating your mutual fund cost basis for dividends you receive and have reinvested back into a mutual fund in the form of additional shares, you’re going to end up being taxed on them twice. This is a common mistake that many taxpayers make. Reinvested dividends should be considered as additional purchases of stock, at different prices.

And this is basically the same if you are talking about a dividend reinvestment plan (or DRIP). You’ll have to pay income tax on the dividends that you receive that are directly invested in brand new shares of stock. And you’ll want to make sure that you update your cost basis records with your additional purchases from the dividends that you reinvest.

Does this sound like a lot of work? It certainly can be. But if you don’t do the work, you may find yourself paying WAY too much in taxes when you finally decide to cash in your mutual fund or DRIP shares.

3. How does dividend reinvesting impact my taxes? How are dividends that are reinvested taxed?

As we have pointed out above, when you reinvest your dividends, you are really receiving a dividend and then buying additional shares of stock. So you pay income tax on the dividends that are paid to you, and the new shares that are purchased are nothing more than capital assets, just like the original stock purchased. If you hold these shares for a year or less before you sell them, you’ll pay taxes on any gains at your marginal income tax bracket. But if you hold the shares for more than one year, any gain that you realize will be taxed at the preferred capital gains rates.

4. Can you recommend a good software package that will ease my tax burden?

Recommend? Nope. But I can tell you that the main contenders when it comes to tax preparation software are Intuit’s TurboTax and MacinTax, and Kiplinger’s TaxCut. If you’re the type who loves filling out questionnaires and answering questions, you might actually enjoy (gasp!) preparing your taxes this way. It has many advantages:

- You don’t have to gather any forms; they’re all in the program already.

- You can revise and revise and revise, without making a mess with white-out or an eraser. Enter your information, see what your tax liability is, and then you can make adjustments, playing out different scenarios to see which is most cost-effective. (You might see that it’s smart to realize some capital gains this year, for example.)

- The software can assist you with decisions. It will ask you questions and either make decisions for you (regarding which forms to use, for example) or offer you some information and ask you to make a choice.

- You can pay less attention to details. Once the program has certain information, it will make sure that it’s carried over to all required places. You don’t have to worry about that.

- Carryovers from year to year get taken care of automatically — if you used the same program to prepare your return last year.

There are, of course, some disadvantages to electronic tax return preparation. The main one is that you have to trust the software, even though you’re still the one responsible for filing your return. There’s always a small chance that the software could cause an error — or that you provided an incorrect number and generated the error yourself. (Of course, even manually prepared returns may contain errors.)

Our best advice regarding tax preparation software is that you try it — at least once. Consider using it as a cross-check for yourself the first year. In other words, fill out your return the old-fashioned way and then do it electronically. Compare the results and you’ll get a much better feeling for how accurate and/or helpful the software is. You can choose whether you want to file your original return or the computer-generated one, and you’ll probably have an idea of which approach to use the following year.

Perhaps the most powerful advantage of tax preparation software is that it lets you play what if games. Once you’ve entered the necessary information, change one variable and see how the bottom line is affected. See what will happen if you get a big raise at work or if you sell some stocks for a sizable capital gain. This can be enormously valuable if you think you might have to pay estimated taxes. The software can help you figure out whether or not you’ll have to pay estimated taxes.

When buying tax preparation software, make sure that the package includes state tax forms for your state if you’d like it to prepare those forms, as well. Verify that it is indeed compatible with your computer system. Make sure that it contains all the forms you’ll need. If you buy the software early in the year, make sure you get an updated final version later in the year, so that you’re preparing your return incorporating the latest information and tax code revisions. You can read more about available software at the software company Web sites — and in many cases, you can get demo versions there as well. Keep in mind that you can often prepare your return online without even buying the software — by using a special Web site and paying a fee online instead.

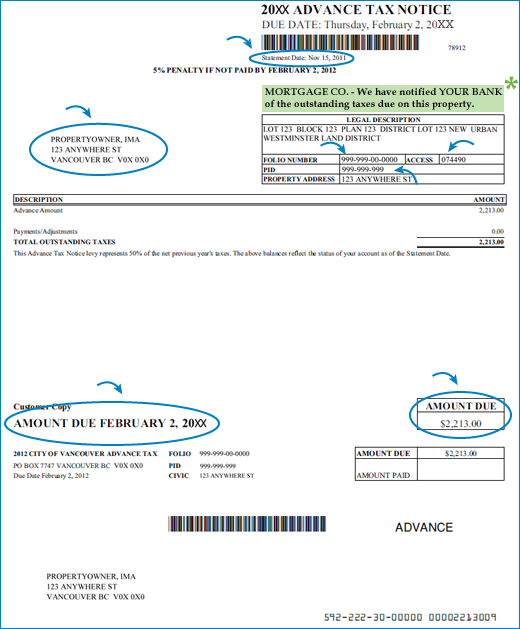

5. What tax form(s) do I receive and from whom?

You’ll generally receive a tax forms package from Uncle Sammy right around the first of the year. That package will include forms that the IRS feels that you might need, based on the forms that you filed last year. If your tax return was prepared by your accountant last year, it’s likely that all that you’ll receive is a post card with your official IRS name and address sticker. That post card will also allow you to order forms if you so chose.

If you find that you need additional forms, your local public library and/or post office will likely have some of the main forms. But some of the more technical forms may not be found there. If you find that you need additional forms, you can order them from the IRS by calling 800-TAX-FORM (800-829-3676). You can also download forms and instructions directly from the IRS Web site. You’ll need an Acrobat reader, but if you don’t have one, you can download one from the Web site at no cost.

6. Do you have any tricks and tips for keeping track of my cost basis? It seems that by investing on a monthly basis and reinvesting the dividends I’m creating a nightmare when I sell stock and have to determine my cost basis.

No real tricks, just hard work — especially if you are doing it by hand. You must simply learn how the tax laws work when dealing with computing your cost basis in your shares, regardless if the shares are in mutual funds or dividend reinvestment plans, and then make the computations.

But, as you suggest, even if you understand this accounting system completely, the paperwork can be a hassle. At the Fool we use our Portfolio Tracker software to do all of the dirty work for our real-money Drip Portfolio online. It’s available for a reasonable price from FoolMart. There are also other computer programs that do the job, such as Quicken from Intuit.

If you’d rather track your investments by hand, that’s perfectly acceptable and — allow us to say — even quite fanciful (maybe turn off the power and light candles while working, too). Many people track their direct investments in a ledger, much like an accountant would in the good old days. One downside is that it’ll be difficult to track your actual performance because share price accounting isn’t automatic when using paper and pencil. The choice is yours.

7. If I sell just part of my holdings in a particular stock, may I use an average cost computation, just like I can with my mutual funds?

Nope. Sorry. When you are dealing with individual shares of stock (and that would also apply to DRIP shares), you have only two options when determining the basis (or cost, for tax purposes) of shares. They are: Specific Identification Method

First In-First Out Method (FIFO)

First, the specific identification method:

Let’s say that you made the following purchases:

June 1, 2000: 100 shares @ $10 each

June 5, 2000: 200 shares @ $11 each

June 10, 2000: 300 shares @ $13 each

The stock is now trading at $15 a stub. You decide you want to sell 300 shares. You also know that you want to sell the shares you originally bought on June 10, 2000. You very emphatically tell your broker that those are the shares that you want to sell, and not the 100 shares bought on June 1, nor the 200 bought on June 5.

Why would you want to do this? Because of the tax implications. If you sell the first 300 shares that you bought, your capital gains will be $1,300 (not including commission adjustments). But by selling the later shares, your capital gains only amount to $600. That could be a tax saving of almost $280 — just by making a simple decision and specifically identifying the shares that you want to sell.

It’s important to think about your current tax and income situation and what you expect your situation to be in the next few years. If you’re getting out of school soon and expect that you’ll soon be in a higher tax bracket, you might want to sell the earliest shares and take a bigger tax hit now. This might make sense if you plan to have a much heftier salary next year and perhaps expect that the stock will have appreciated considerably, as well. On the other hand, if the last shares you bought have not yet been held long enough to qualify for the lowest capital gains tax rate, it might be worth it to sell the ones you’ve held longer. Look at your options from many different perspectives and see which one saves you the most money — both now and in the long run.

If you decide to use the FIFO method (which is actually the default method that you must use if you can’t qualify for the specific share method), the first securities you bought are the first ones sold. The basis of the stock for capital gains purposes is the cost of the first securities you purchased. In the example above, using the FIFO method could very well have cost you an additional $280 in tax dollars. For more details on using the specific share method, click here.

8. Whose social security number do I submit on a custodial account, and who pays the taxes?

Remember that while you (or someone else) may be the custodian of this type of account, the account really belongs to the child. The custodian is simply involved in managing the account, protecting the assets in the account, and generating growth and/or income within the account. Since the account belongs to the child, so do any income or gains (and the associated taxes) generated by the account. This is one reason that custodian accounts are so very popular: The earnings and gains shift to the child and are (usually) taxed at a lower rate. Because of this fact, the tax return is filed by the child (or by the custodian on behalf of the child), and the child’s social security number is used to report the income and gains.

But let’s not forget the kiddie tax. While this income still belongs to the child, some of it could very well be taxed at your personal tax rate via the kiddie tax rules. Obviously, having the child’s income taxed at your individual tax rate will cancel some of the tax benefits of establishing a custodian account — so it’s something that you’ll want to manage as carefully as possible. For more on the kiddie tax, click here.

It’s very important to remember — always — that these funds really do belong to the child. They aren’t yours to do with as you please. And when your child reaches the age of majority, look out. Because the money is all his or hers, to do with as they please. Let that thought haunt you for a few minutes.

(We pause to permit the haunting)

Okay, now let’s look at the various kinds of custodial accounts that are out there. Two of the biggies are the UGMA and the UTMA. Ugma? Utma. Gee, that sounds like a caveman asking a cave woman out on a date. Nevertheless, the Uniform Gift to Minors Account and the Unified Transfers to Minors Account are the two main types of custodial accounts that you’ll see. And if you are interested in establishing an custodial account, it’s virtually certain that you’ll use one of these two account types. Get all the information you’ll need about investing for your kids here.

9. What’s the difference between short-term and long-term capital gains? How do I know which one I should pay?

What rate applies to you specifically? Well, it all depends on:

- the type of asset you sold

- your cost basis

- the length of time you held the asset before selling it

- your income level

Qualifying for the lowest new rates are stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and many other capital assets. Taxed at a slightly higher rate are business or rental real estate, collectibles, depreciation, and some other things. For this question, we’ll be referring to the rates and rules pertaining to securities investments.

There are two holding periods for capital assets sold. Assets held for a year or less are considered short term. Those held for more than one year are considered long term.

Here’s the bottom line:

If you’re in the 15% tax bracket: