The Effective Tax Rate Myth and the Fact

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Key Points

Nonetheless, the White House and Treasury Department continue to assert that the U.S. has a lower METR than Canada by failing to properly account for sales and property taxes.

The U.S. METR varies by industry, from 26.7 percent for transportation to 39.3 percent for communications.

The U.S. average effective tax rate on corporations (AETR) is irregular from year to year due to the complexity and instability of the corporate tax code.

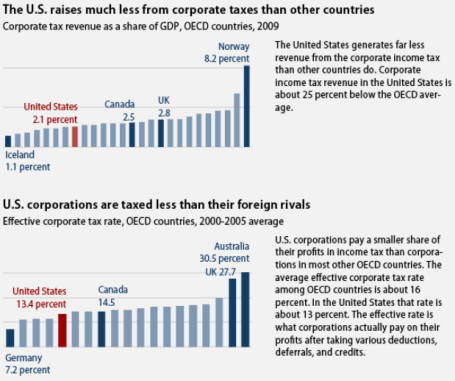

Excessively high U.S. corporate tax rates have shrunk the U.S. corporate sector and reduced corporate tax revenues.

The statutory corporate income tax rate of the United States is infamously one of the highest in the world, while effective tax rates on capital investments appear to be high and dispersed.

For businesses, it is not unusual to see their effective tax rates, regardless of how these are defined, being lower than their statutory tax rates. This results from tax preferences (“loopholes,” if using a pejorative term) that are more generous than the economic costs of generating taxable income.

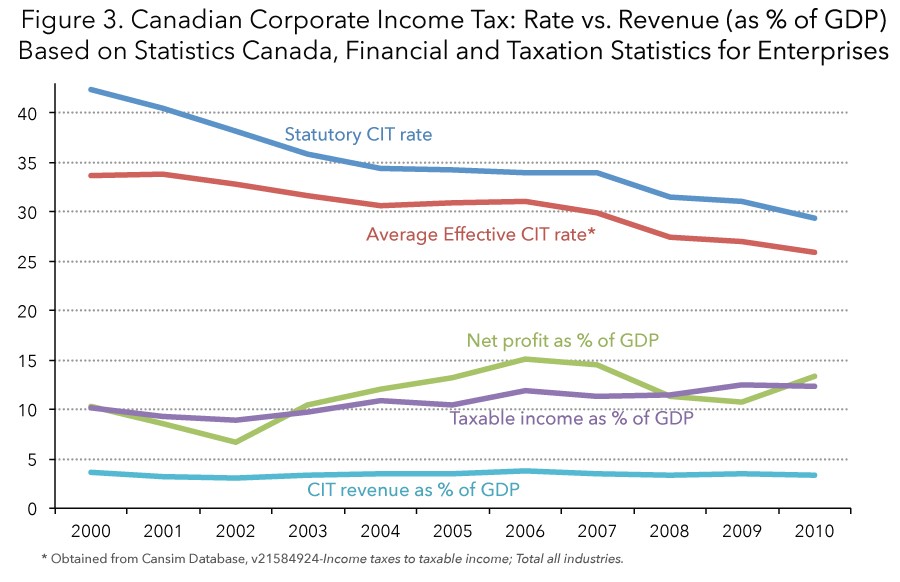

For economists, it is also commonly understood that effective tax rates follow the trend of statutory tax rates in the long run. The long-run divergence between these two rates is not caused by the economic cycle but by irregular provisions of various conditional tax preferences. These irregular conditional tax allowances or credits narrow the tax base, which often goes hand in hand with rather high statutory tax rates.

The combination of a narrow tax base and an otherwise unnecessarily high tax rate hurts business investment in general by benefiting only those investors who can use available tax preferences. This creates an uneven playing field, resulting in a misallocation of capital toward tax-favored activities as well as making the tax system more complex to comply with and administer. The U.S. government, moreover, puts itself at a disadvantage with high statutory corporate tax rates, since businesses are encouraged to shift profits out of the U.S. with transfer pricing and tax-efficient financing structures to low tax rate jurisdictions, thereby reducing revenues that could be used to finance federal government services.

This paper evaluates the U.S. corporate effective tax rate by two general methods: one is the marginal effective tax rate (METR) on new investments and the other is the average effective tax rate (AETR). We conclude that the problem with the U.S. corporate income tax system is much broader than the high federal-state combined statutory tax rate of over 39 percent. The corporate tax system also undermines economic growth with a non-neutral treatment of business activities.

The Corporate Marginal Effective Tax Rate

Marginal effective tax rate (METR) analysis has been a well-documented and extensively applied analytical tool for measuring tax impacts on investment and capital allocation distortions since the 1980s.[1] We have applied this analysis systematically since 2005 for the purpose of ranking Canadian business tax competitiveness among the G-7, the OECD member countries, and an expanding list of other countries.[2]

Tax competitiveness is relevant due to the increased capital mobility across borders associated with globalization. Taxes that impinge on investment reduce the economy’s capacity to produce goods and services in the future, which can be referred to as the “inter-temporal” distortion arising from capital taxation. Taxes that vary by business activity also cause inter-sectoral, inter-asset, financial, and organizational distortions that result in a less than optimal use of capital resources in the economy. A more level playing field among business activities shifts resources from investments earning low pre-tax rates of return on capital to those earning higher pre-tax returns, thereby improving the allocation of capital in the economy.

Therefore, a country’s competitiveness is hurt by taxation that undermines productivity through investment. There is no doubt that the free-market system of the U.S. has been a beacon for entrepreneurs and capital investors. But it can do better with multinational companies if its corporate tax system can be reformed to combine a lower tax rate with a broader tax base that facilitates capital investment in general rather than benefiting only a few who are able to navigate through a complex tax structure.

Marginal Effective Rate Calculation

The marginal effective tax rate measures the tax impact on capital investment as a portion of the cost of capital. In considering a new investment, a firm will, like any rational investor, allocate capital to maximize profit. The assumption that firms are profit maximizers provides a starting point for calculating the METR. Firms increase investment when marginal returns cover marginal costs and reduce scale when marginal returns are less than marginal costs. Since it is only the marginal cost of investment, rather than the marginal return, that is directly observable, the METR uses marginal cost to calculate the measure. The METR is evaluated as the effective tax cost as a share of marginal investment costs net of economic depreciation and risk,[3] which is also the pre-tax rate of return on capital. For example, if the pre-tax rate of return on capital (i.e.. the tax-inclusive cost of capital) is 20 percent at the profit-maximizing point and the post-tax rate of return on capital (i.e.. the tax-exclusive cost of capital) is 10 percent, the METR is 50 percent.

U.S. among Least Competitive on Marginal Effective Tax Rate

In our annual business tax competitiveness ranking,[4] which is based on our calculation of marginal effective tax rates by country, the U.S. has been among the least tax-competitive countries for capital investment over the past nine years (see Table 1). The Canadian METR has been lower than that in the U.S. since 2007 thanks to the steady reduction in corporate income tax rates, elimination of the capital tax on non-financial corporations, and provincial sales tax harmonization that eliminated sales taxes on purchase of capital goods, all of which were a concerted effort made by both the federal and most provincial governments under different political parties over the past decade.