Lessons from Japan s lost decade why America s experience may be wors Online Library

Post on: 29 Июль, 2015 No Comment

Page/Link:

Page URL:

HTML link:

The ongoing financial and economic difficulties in the United States have not only defied many earlier forecasts of quick recovery, including those from the Federal Reserve, but are also showing signs of stress that many experts are calling the worst since the Great Depression. In spite of the ever-worsening outlook, policy responses from Washington so far have been mostly ad hoc, with the Fed and government officials running with fire extinguishers to Bear Stearns one day and Fannie Mae the next. The debate in Congress has also centered on how to avoid a repeat of the crisis in the future, not how to contain and overcome the ongoing meltdown. Moreover, there seems to be no Plan B or Plan C in case things get even worse.

This lack of comprehensive approach in the face of such massive danger may be due to the fact that the current administration is already a lame duck and those with policy experience from the 1930s who can tell us what to expect are no longer with us. The lack of a thorough diagnosis of the problem and its possible remedies, in turn, has multiplied the fearfulness of both market participants and the general public, greatly worsening the deflationary pressure in the economy. The fact that European and Chinese real estate bubbles are also bursting is adding to the global gloom.

The United States (and the world) is extremely fortunate, however, to have the recent example of Japan before us. The second-largest economy in the world went through something very similar just fifteen years ago, and its experience can tell us volumes about what to expect in this kind of crisis. Although many Americans may scoff at the idea that the United States has something to learn from Japan, the truth is that the magnitude of the house price bubble in the United States from 1999 to 2006 (a 138 percent increase) was virtually identical to the one Japan experienced between 1984 and 1991 (a 142 percent increase). Furthermore, according to the house price futures listed in Chicago Mercantile Exchange, the magnitude of the decline in house prices (33 percent decline from the peak in four years) is nearly the same as that of the earlier Japanese experience (37 percent decline from the peak in four years).

Similarities do not end there. The largest estimate of losses financial institutions may incur in the current crisis was provided by the International Monetary Fund in its 2008 Global Financial Stability Report, which placed the price tag at $945 billion. This amount is virtually identical to the total non-performing loans Japanese banks wrote off during the post-bubble period, $952 billion at the exchange rate of 105 yen to the dollar.

Although the United States has not experienced a lost decade yet, many signs are far worse this time around compared to Japan fifteen years ago. For example, the much-criticized Japanese banking problems in the 1990s never reached the point where the banks distrusted each other in the all-important interbank market and the central bank had to enter the market on the daily basis to make sure banks were able to meet their payment responsibilities. In both the United States and in Europe this time around, however, the lack of trust between the banks is so serious that central banks have been forced to provide liquidity directly for over a year, with no end in sight.

Japanese banks also did not depend much on foreign capital injections, while banks in the United States and some European banks had to beg the sovereign wealth funds of some of the least democratic nations in the Middle East and Asia for capital in order to stay afloat. The credibility of rating agencies and mark-to-market accounting, once heralded as a pillar of transparency and accountability, also collapsed as markets for many highly rated financial assets simply disappeared. It is no wonder that many experts are calling the current crisis the worst since the Great Depression.

The ailment is called a balance sheet recession.

Although there are many differences between the Japanese and U.S. experiences, the Japanese lessons provide the nearest thing to a roadmap of a post-bubble economy, and U.S. policymakers will be able to greatly shorten the pain and suffering of the American people if they put those lessons to good use. In particular, recessions brought about by the bursting of a nationwide asset price bubble are fundamentally different from ordinary recessions in many key aspects.

First, the bursting of a bubble invariably means destruction of many private-sector balance sheets as assets bought with borrowed funds collapse in value while the debt incurred to purchase those assets remains at its original value. Many businesses and households may find themselves with negative net worth. When these businesses and households start paying down debt or increasing savings in order to regain their financial health and credit ratings, the economy enters what may be called balance sheet recession where monetary easing by the central bank fails to stimulate the economy or asset prices. Monetary policy loses its effectiveness because those with debt overhangs are not interested in increasing borrowing at any interest rate.

The Bank of Japan brought interest rates down from over 8 percent in 1991 to almost zero in 1995, but there was absolutely no response from the economy or asset prices, which continued to fall. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke brought interest rates down from 5.25 percent in September 2007 to 2 percent by April 2008 in the fastest monetary easing in the Fed’s history, but the economy and house prices continued to fall. With so many banks and households in the United States worried about the health of their balance sheets, further monetary easing by the Fed is likely to fare no better than the Japanese easing to zero interest rates fifteen years earlier.

With nobody borrowing money and everybody paying down debt or increasing savings, even at zero interest rates, the deflationary spiral becomes a real possibility in this type of recession. This is because those unborrowed savings and debt repayment represent leakage to the income stream, and if left unattended, the economy will continue to lose aggregate demand equivalent to the unborrowed amount until either private sector balance sheets are repaired, or the sector has become too poor to save any money. The United States fell into this spiral during the Great Depression, the largest of balance sheet recessions, and lost 46 percent of its GDP in just four years. The unemployment rate also rose to 25 percent by 1933.

In contrast, Japan’s GDP never fell below the bubble peak both in nominal and real terms, and the unemployment rate never reached 6 percent. This is a remarkable achievement in view of the fact that commercial real estate prices in Japan fell a whopping 87 percent nationwide from their peak and Japan’s corporate sector continued to pay down debt for a full ten years from 1995 to 2005. Net debt repayments by companies in some years reached as much as [yen]30 trillion or 6 percent of Japan’s GDP.

Japan’s GDP never fell in spite of the massive drop in asset prices and massive increase in private-sector debt repayment because the government borrowed and spent the increased savings and debt repayment that represented the leakage to the income stream. With the government actively putting this sum back into the income stream through its fiscal policy, there was no reason for the GDP to contract. In other words, Japan proved to the world that, even if real estate prices decline by 87 percent and the private sector is obsessed with debt minimization instead of profit maximization, it is still possible to keep the GDP from falling as long as the government puts in an appropriate-sized fiscal stimulus from the beginning and maintains that stance until private-sector balance sheets are repaired.

Moreover, with the government keeping the GDP from falling, people will have the income to pay down debt. As long as they have the income to pay down debt, at some point, the debt overhang will be removed. Once it is removed, the economy returns to the normal or textbook world where people are again looking forward. With the private-sector obsessed with paying down debt, there is also no danger of government spending crowding out private-sector investments.

These are hugely important lessons for the United States, where house prices are still falling and some financial assets have lost more than 80 percent of their values. With its employment rate falling for eight months in a row, it is probably safe to say that the United States is now fully into a balance sheet recession.

This means the key policy response should be an increase in government spending to keep GDP from falling, so that households and banks have the revenue to repair their balance sheets. Microeconomic responses, such as what to do with Bear Stearns or Fannie Mae, are important, but they are no substitute for a comprehensive macroeconomic response to maintain GDP because without revenue, no attempt to repair private-sector balance sheets will succeed. Monetary easing is probably better than nothing, but it should not be relied on as the principle policy response when the private sector is minimizing debt and is in no position to respond to lower interest rates.

When the private sector is obsessed with their balance sheet woes and the danger of falling into a deflationary spiral is real, increasing government spending is far more efficient than a tax cut in boosting domestic demand. It is more efficient because the entire amount of government spending will add to aggregate demand while a large part of any tax cut may be used by the private sector to increase savings or decrease debt as we have seen in the recent U.S. income tax rebate. Japan tried both, but it was largely the government spending that kept its GDP and employment from falling.

Not everything went well in Japan. Because the concept of balance sheet recession was not yet known in economics in the 1990s, trial-and-error solutions with largely ineffective monetary, structural, and other policies continued. Moreover, because of the lack of conceptual understanding, the critical importance of fiscal policy in maintaining an income stream in this type of recession was never fully appreciated, with the result that every time the economy showed signs of recovery with fiscal stimulus, it was assumed that the conventional pump-priming had worked, and the stimulus itself was cut in order to rein in the budget deficit. But no sustained recovery is possible in a balance sheet recession without the recovery of private-sector balance sheets, and premature withdraw of stimulus invariably resulted in economic downturn. That prompted another fiscal stimulus, only to see it cut again after the improvement in the economy. This stop-and-go fiscal stimulus lengthened the total time of Japan’s recession by at least five years, if not longer. In the United States, a similar premature withdrawal of fiscal stimulus in 1937 also lengthened the duration of the Great Depression until the onset of World War II.

The United States would do well to make sure that this mistake is not repeated. In particular, Washington should enact a medium-term (at least three to five years) seamless package of government spending to assure the public that they can count on the government to keep the economy going for the entire period. Such a commitment will go a long way in removing the fear of falling into a deflationary spiral and allow the public to plan for an orderly repair of balance sheets. This stance by the government should be maintained until private-sector balance sheets are repaired and people are willing to look forward again. If and when that point is reached, the government must embark on fiscal consolidation in order to avoid crowding out private-sector investments.

THE SECOND FRONT IN FIGHTING A BALANCE-SHEET RECESSION

The credit crunch brought about by the lack of capital in the battered banking system is the second front in fighting balance sheet recession. A credit crunch, which makes everything more difficult as the blood circulation of the economy is impaired, must be stopped before it stops the economy. The Fed’s survey of senior loan officers of U.S. banks already indicates that this crunch is well underway, especially in the areas of housing and commercial real estate.

This problem was dealt with in Japan by the government injecting capital into the banks first in March 1998 and again in March 1999. These two blanket injections virtually eliminated the crunch. The United States will do well to implement similar measures for its banks once it becomes politically feasible to do so.

The political dimension here is extremely important because bailing out rich fat bankers is unpopular in any country. In Japan, it was Prime Minister Kiichi Miyazawa who first proposed to repair the banks with public funds back in 1992, or just two years after the bursting of the bubble. Unfortunately, he was shouted down by the angry and ignorant media, who argued that bankers must repent their sins and cut their salaries first. The public outcry not only forced Miyazawa to retract his proposal, but also made it impossible for politicians in Japan to talk about such proposals for a full five years. The devastating credit crunch which started in late 1997 finally made people realize that healthy banks are in their own interest, but precious time was lost in the meantime.

It was indeed ironic to see Japan’s Finance Minister Fukushiro Nukaga telling U.S. Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson about the need to use public funds to fix the U.S. banks at the G7 meeting held in Tokyo in February 2008. Paulson agreed with the need to strengthen U.S. bank capital, but could not commit his government to do so. The conversation between the two men was the exact replica of the exchange that took place between U.S. and Japanese officials prior to 1998, but with the parties reversed.

Some may argue that U.S. banks have already replenished their capital via foreign sovereign wealth funds. However, there are over 8,400 banks in the United States today, and only the top twenty of them are probably in a position to avail themselves of foreign help. The rest are unlikely to find much help in Abu Dhabi or Beijing. But with so many banks having the same problem at the same time, it is difficult for individual banks to raise capital at home. The only option left for these banks to meet capital-asset ratios, therefore, is to cut lending.

The Fed has already lent tons of liquidity to the banks so that they can meet their daily clearing requirements, as noted above. But what banks need in order to assume risk and resume their lending is capital, not liquidity. And only the government can provide capital; the Fed can only provide liquidity.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation has already indicated that there are over one hundred banks on their watch list. That is bad enough. But from a macro perspective, it is the rush by the remaining 8,300 banks to cut lending in order to meet capital-asset ratios and avoid being put onto the FDIC watch list that is far more damaging to the economy. Since a credit crunch can easily sink the economy, Washington would do well to put together a program of capital injection to avoid that outcome.

If and when that becomes possible, the Japanese experience suggests that government should not impose too many conditions on the injection when the goal of such injection is to end the credit crunch. This is because banks have the fight to refuse a government capital injection if the conditions appear too burdensome. But if they reject the injection, the credit crunch will not abate, and the broader economy will suffer.

Indeed, when the Japanese government passed the law authorizing capital injection with many conditions attached as requested by the U.S. government, not a single bank applied for capital injection. The bankers’ decision was easy: observers ranging from bank analysts to the Financial Times all agreed that banks should not take the money but instead cut lending to make themselves lean and mean. Even though that was the right thing to do at the level of individual banks, if all banks moved in that direction at the same time, the economy would have collapsed. In the end, the government dropped the conditions and after much arm-twisting reminiscent of the capital injection implemented by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1933 on which the Japanese scheme was modeled, the banks finally accepted the capital and the credit crunch was ended.

Fixing the health of individual banks and ending the credit crunch are two often contradictory goals. Faced with the choice, policymakers should prioritize ending the credit crunch first because it can kill both the economy and the banks if left unattended. The health of the individual banks should be pursued by government regulators only after the systemic risk to the economy and the banking system has subsided.

Critics will also argue that limiting government help to banks is not fair. But this is akin to the kidney and liver complaining when heart gets the special treatment. If the heart stops, everybody dies. Moreover, the U.S. and Japanese capital injections in 1933 and 1999 respectively ended up costing taxpayers nothing, as banks paid back the money in due course. Lastly, Citibank and others are paying upwards of 11 percent or more for capital from foreign sovereign wealth funds. The U.S. government replacing foreign sovereign wealth funds will keep that money within the United States, an important consideration when the country is already running such a large current account deficit.

The Japanese experience suggests that, in a balance sheet recession, a medium-term seamless program of government spending and a program of blanket injection of capital to the banks are needed to provide a floor to the economy. Although a full recovery will have to wait for the recovery of private-sector balance sheets, these two measures will eliminate the danger of falling into a deflationary spiral and provide the revenue for the private sector to repair its balance sheets. These measures are needed not just in the United States, but also in parts of Europe and China. If one or both components of Plan B remain unattainable for policymakers, however, investors and the public in general may want to stay cautious, as private-sector efforts to repair balance sheets have the potential to tip the economy into a 1930s-like deflationary spiral.

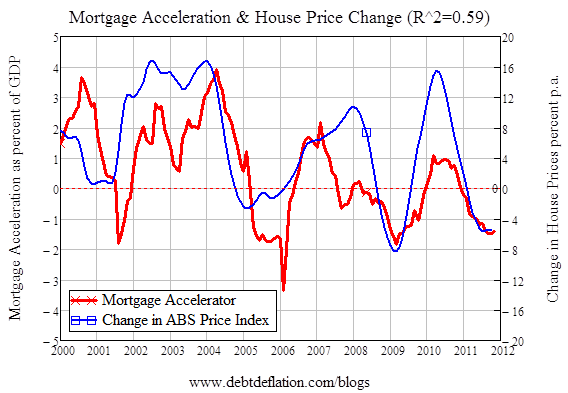

[ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

It was indeed ironic to see Japan’s Finance Minister Fukushiro Nukaga telling U.S. Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson about the need to use public funds to fix the U.S. banks at the G7 meeting held in Tokyo in February 2008. Paulson agreed with the need to strengthen U.S. bank capital, but could not commit his government to do so. The conversation between the two men was the exact replica of the exchange that took place between U.S. and Japanese officials prior to 1998, but with the parties reversed.

Richard Koo, formerly with the New York Federal Reserve, is the chief economist of Nomura Research Institute in Tokyo and the author of the recently published book, The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics: Lessons from Japan’s Great Recession (John Wiley and Sons, Singapore, 2008).