In an M A deal what is an accretion

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Related Topics

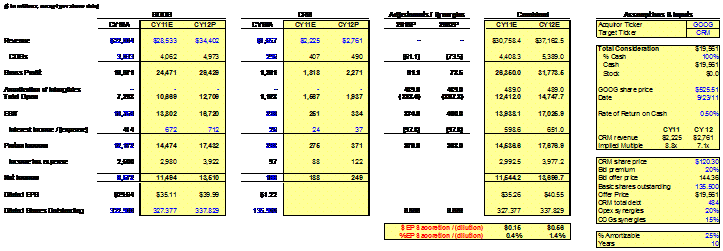

When you buy a company, it's difficult to tell whether it will ultimately be helpful to your earnings (accretive) or hurtful to your earnings (dilutive). an accretion-dilution analysis is a way to help clear that up for you.

If you are the acquirer (Company A) and you want to acquire Company B, you take your operating earnings and combine it with Company B's. However, in a transaction, there are also other effects that need to be considered in your analysis.

Synergies / Dis-synergies: In most cases, M&A deals don't happen just to happen — there has to be something in it for the acquirer to want to pay up for Company B (cut operating expenses, gain economies of scale, revenue growth through added distribution, etc), and there may be some negative side-effects of the transaction (if A used to be a customer of B, then the revenues that B used to get from A will go away once A acquires B; if competitors of A are customers of B, ownership by A may be enough to make A's competitors take their business elsewhere, etc).

Integration Spend: Once A acquires B, it's not likely that synergies will be able to be realized without some investment to make the companies fit together. This might include things like technology integration, severance pay for duplicate positions, money spent on hiring consultants to help with the integration effort, etc.

Additional Amortization of Intangibles: When A buys B, they're likely pay a premium to what B is currently trading at (assuming B is a public company). This premium typically amounts to anywhere from 15% — 30% above B's equity market value (control premium). By acquiring B's shares, A is taking on everything B has on its balance sheet (assets and liabilities; as you may recall, the book value of equity is what you get when you take assets and subtract out liabilities). Market value of equity is rarely equal to book value of equity; in most cases, the market value is higher because the market's expectations of future growth are built into it. This difference in value needs to be accounted for somehow; maybe B's brand is worth something (goodwill) or there are other intangibles (e.g. customer lists, patents, etc) that have some worth. You make an assumption about how much these intangibles are worth, and allocate a percentage of the excess purchase price (market value equity — book value of equity) to intangibles. However, while goodwill doesn't get amortized, other intangibles do (customer lists aren't good forever); you make an assumption about how many years the written-up intangibles have value for and divided the intangibles by this to figure out your annual amortization expense.

Financing Fees: Did A raise debt to acquire B? Or did they simply use equity? If they raised debt, there is now new interest expense that needs to be included. If A used an investment bank to help raise the debt, the financing fees paid to the bank need to be capitalized and amortized (similar to intangibles, above)

Fees: Assuming A hires an investment bank to help facilitate the transaction, they will have to pay them an advisory fee. This is usually just a one-time fee that is taken after transaction close, but it still needs to be included in the analysis.

So now you have A's operating income + B's operating income + Pre-tax adjustments (ie: net synergies, integration, amortization including amortization of financing fees, interest expense, and M&A fees). Add these together to get your pro forma operating income. Tax-effect it to get your pro forma net income. The pro forma count of number of shares outstanding for A depends on whether they issued any equity to acquire B. If they did, you add the amount of equity issued to their current standalone shares outstanding count and divide pro forma net income by pro forma share count (If no shares were issued, pro forma share count will equal standalone share count).

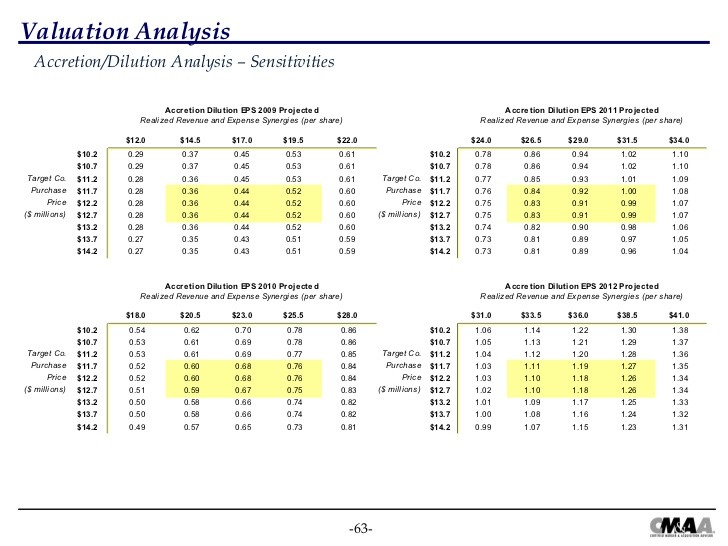

What you're left with is pro forma earnings per share. Compare this against A's standalone earnings per share for the year the transaction is expected to close, and the following 2 or 3 years (need to give some time for the synergies to kick in). If pro forma EPS is less than A's standalone EPS, then the transaction is dilutive; if it is greater, then it's accretive. Take the difference between pro forma EPS and standalone EPS and divide that by standalone EPS to determine the percentage accretion.

Probably easier to see this done in a spreadsheet, Macabacus might be helpful if you want an example to go off of: Accretion/Dilution | M&A Model | Macabacus