How the recession turned middleclass jobs into lowwage jobs The Washington Post

Post on: 10 Май, 2015 No Comment

By Brad Plumer February 28, 2013 Follow @bradplumer

The U.S. job market is slowly improving, and most economists expect that gradual recovery to continue this year. Yet one of the most disturbing trends of the recession is still very far from being reversed. America’s middle-class jobs have been decimated since 2007, replaced largely by low-wage jobs.

A recent presentation from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco lays out the situation clearly. The vast majority of job losses during the recession were in middle-income occupations, and they’ve largely been replaced by low-wage jobs since 2010:

Mid-wage occupations, paying between $13.83 and $21.13 per hour, made up about 60 percent of the job losses during the recession. But those mid-wage jobs have made up just 27 percent of the jobs gained during the recovery.

By contrast, low-wage occupations paying less than $13.83 per hour have utterly dominated the recovery, with 58 percent of the job gains since 2010. (This data all comes from an earlier report (pdf) from the National Employment Law Project.)

That’s put downward pressure on wages: [M]any middle-class workers have lost their jobs and, if they have been able to secure new employment at all, find themselves earning far lower wages post-recession, the San Francisco Fed notes. [O]n average over the next 25 years, these workers will earn 11% less than similar workers who retained their jobs through the recession.

The jobs of the future? (Washington Post)

So what types of low-wage jobs are we talking about? Nearly 40 percent of the jobs gained since the recovery began — about 1.7 million — have come from three low-wage sectors: food services, retail, and employment services (that last is a sweeping category encompassing jobs like office clerks and sales representatives).

As the San Francisco Fed presentation notes, just four low-wage sectors now make up nearly 12 percent of the workforce in 2011: retail sales, cashiers, office clerks, and food preparation and service workers. [T]hese occupations are crucial to the support and growth of major industries across the country, but many of these workers do not earn enough to adequately support their families, even at a subsistence level.

By contrast, many mid-wage industries, such as construction, manufacturing, insurance, real estate and information technology, have either stagnated or grown too slowly to make up for their pre-recession losses.

What’s more, the NELP report notes, budget cuts to state and local governments have taken away a major source of mid- and higher-wage jobs. And a separate chunk of middle-wage jobs — including carpenters, painters, and electricians — are still waiting for the U.S. housing market to recover.

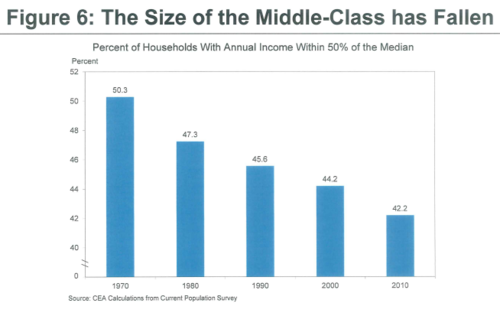

This isn’t a new phenomenon: Over the past decade high-wage and low-wage jobs have been growing at a decent clip. But that middle rung continues to get hollowed out. Mid-wage jobs endured a major drop after the 2001 recession, largely stagnated during the 2000s, and have now declined even further in the most recent downturn. (See this graph for a look at the historical trend.)

Are robots to blame? (Getty)

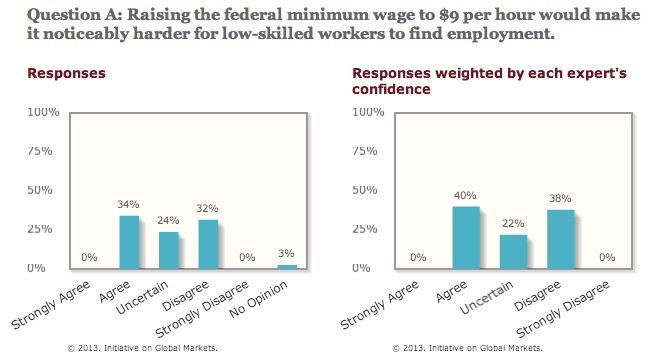

Economists have been debating the underlying causes of this growing divergence for years now. Some, such as Harvard’s Lawrence Katz and Claudia Goldin, argue that new technologies and machines are now displacing mid-wage jobs at the assembly line and elsewhere. Others, such as Larry Mishel of the Economic Policy Institute, point to explicitly political factors, from the decline of labor unions to trade liberalization to the dwindling minimum wage.

Yet whatever the cause, the hollowing-out of mid-wage jobs has been accelerating sharply during the recession. And if the trend continues, the NELP report notes, it’s very likely to exacerbate income inequality in the United States.

The San Francisco Fed presentation, for its part, spends some time discussing how to lift people out of that lower-middle-income rung — though it shies away from ideas like raising the minimum wage or bolstering labor unions. Instead, there’s a lot of focus on vocational training for workers, which has had only mixed success of late:

[Business, banks, and nonprofit groups] noted that many unemployed [lower-middle-income] individuals, seeing few employment opportunities for which they are qualified on the job market, return to school to improve their qualifications. When students graduate from vocational training programs or community college coursework, however, they must compete with one another in a tight job market.

Respondents explained that some students do not graduate or complete their training programs before dropping out due to expenses, household demands, or other conflicts. Additionally, whether or not they have graduated, these students now have varying degrees of student debt, layered on top of existing debt accumulated while they were unemployed.

The presentation goes on to suggest a few other small-bore remedies, from affordable-housing programs to making job-training programs cheaper and easier. But there’s a larger trend taking place in the U.S. economy — in which low-wage jobs are displacing middle-wage jobs — that’s becoming increasingly difficult to fight against with small policy tweaks.

Further reading:

—One recent theory for the disappearance of middle-class jobs is that robots and technology are displacing workers in manufacturing and other mid-wage occupations. Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee have a fuller explanation of this theory in this essay. which is worth reading.

—A separate theory is that political trends deserve much of the blame, including: a stagnant minimum wage, the decline of unions, trade liberalization, and deregulation of key industries. See Dylan Matthews for more on this (often heated) debate among economists.