Fundamental Stock Analysis

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

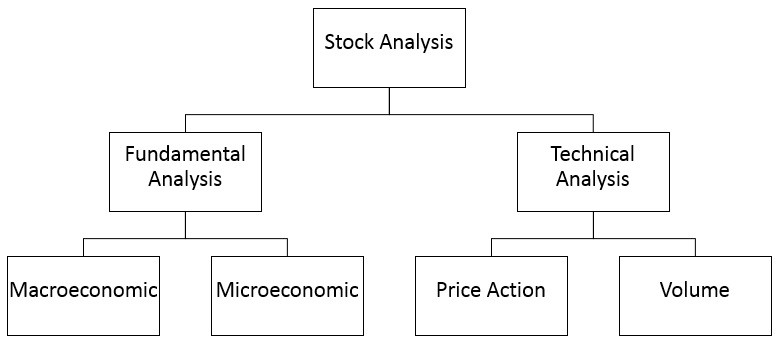

Fundamental Stock Analysis is typically more closely tied to buy and hold investors, whereby day traders use solely technical analysis and most swing traders use both fundamental and technical stock analysis. Technical analysis is specifically important for swing traders with a very short time horizon (that is, a couple of days or just a few weeks). Most swing trading software uses only technical analysis but the Stocknod neural network uses a blended custom recipe of both technicals and fundamentals. Stock fundamental analysis can answer questions that are beyond the scope of technical analysis, such as Why is this security price moving?

Stock Fundamental Analysis (Value, Growth, Income, GARP, Quality)

Many people rightly believe that when you buy a share of stock you are buying a proportional share in a business. As a consequence, to figure out how much the stock is worth, you should determine how much the business is worth. Investors generally do this by assessing the companys financials in terms of per-share values in order to calculate how much the proportional share of the business is worth. This is known as fundamental analysis by some, and most who use it view it as the only kind of rational stock analysis.

Although analyzing a business might seem like a straightforward activity, there are many flavors of fundamental analysis. Investors often create oppositions and subcategories in order to better understand their specific investing philosophy. In the end, most investors come up with an approach that is a blend of a number of different approaches. Many of the distinctions are more academic inventions than actual practical differences. For instance, value and growth have been codified by economists who study the stock market even though market practitioners do not find these labels to be quite as useful. In the following descriptions, we will focus on what most investors mean when they use these labels, although you always have to be careful to double-check what someone using them really means.

Value. A cynic, as the saying goes, is someone who knows the price of everything and the value of nothing. An investors purpose, though, should be to know both the price and the value of a companys stock. The goal of the value investor is to purchase companies at a large discount to their intrinsic value what the business would be worth if it were sold tomorrow. In a sense, all investors are value investors they want to buy a stock that is worth more than what they paid. Typically those who describe themselves as value investors are focused on the liquidation value of a company, or what it might be worth if all of its assets were sold tomorrow. However, value can be a very confusing label as the idea of intrinsic value is not specifically limited to the notion of liquidation value. Novices should understand that although most value investors believe in certain things, not all who use the word value mean the same thing.

The person viewed as providing the foundation for modern value investing is Benjamin Graham, whose 1934 book Security Analysis (co-written with David Dodd) is still widely used today. Other investors viewed as serious practitioners of the value approach include Sir John Templeton and Michael Price. These value investors tend to have very strict, absolute rules governing how they purchase a companys stock. These rules are usually based on relationships between the current market price of the company and certain business fundamentals. A few examples include:

- Price/earnings rations (P/E)

- Dividend yields above a certain absolute limit

- Book value per share relative to the share price

- Total sales at a certain level relative to the companys market capitalization of market value

Growth. Growth investing is the idea that you should buy stock in companies whose potential for growth in sales and earnings is excellent. Growth investors tend to focus more on the companys value as an ongoing concern. Many plan to hold these stocks for long periods of time, although this is not always the case. At a certain point, growth as a label is as dysfunctional as value, given that very few people want to buy companies that are not growing.

Growth investors look at the underlying quality of the business and the rate at which it is growing in order to analyze whether to buy it. Excited by new companies, new industries, and new markets, growth investors normally buy companies that they believe are capable of increasing sales, earnings, and other important business metrics by a minimum amount each year. Growth is often discussed in opposition to value, but sometimes the lines between the two approaches become quite fuzzy in practice.

Income. Although today common stocks are widely purchased by people who expect the shares to increase in value, there are still many people who buy stocks primarily because of the stream of dividends they generate. Called income investors, these individuals often entirely forego companies whose shares have the possibility of capital appreciation for high-yielding dividend-paying companies in slow-growth industries. These investors focus on companies that pay high dividends like utilities and real estate investment trusts (REITs), although many times they may invest in companies undergoing significant business problems whose share prices have sunk so low that the dividend yield is consequently very high.

Quality. Most investors today use a hybrid of value, growth, and GARP approaches. These investors are looking for high-quality businesses selling for reasonable prices. Although they do not have any shorthand rules for what kind of numerical relationships there should be between the share price and business fundamentals, they do share a similar philosophy of looking at the companys valuation and at the inherent quality of the company as measured both quantitatively by concepts like Return on Equity (ROE) and qualitatively by the competence of management. Many of them describe themselves as value investors, although they concentrate much more on the value of the company as an ongoing concern rather than on liquidation value.

Warren Buffett of Berkshire Hathaway is probably the most famous practitioner of this approach. He studied under Benjamin Graham at Columbia Business School but was eventually swayed by his partner, Charlie Munger, to also pay attention to Phil Fishers message of growth and quality.

GARP. Aside from being the name of the title character played by Robin Williams in John Irvings The World According to Garp, is an acronym for growth at a reasonable price. The world according to GARP investors combines the value and growth approaches and adds a numerical slant. Practitioners look for companies with solid growth prospects and current share prices that do not reflect the intrinsic value of the business, getting a double play as earnings increase and the price/earnings (P/E) ratios at which those earnings are valued increase as well.

One of the most common GARP approaches is to buy stocks when the P/E ratio is lower than the rate at which earnings per share can grow in the future. As the companys earnings per share grow, the P/E of the company will fall if the share price remains constant. Since fast-growing companies normally can sustain high P/Es, the GARP investor is buying a company that will be cheap tomorrow if the growth occurs as expected. If the growth does not come, however, the GARP investors perceived bargain can disappear very quickly.

Quantitative Stock Fundamental Analysis Buying Based on Numbers

Pure quantitative analysts look only at numbers with almost no regard for the underlying business. The more you find yourself talking about numbers, the more likely you are to be using a purely quantitative approach. Although even fundamental analysis requires some numerical inputs, the primary concern is always the underlying business, focusing on things like managements expertise, the competitive environment, the market potential for new products, and the like. Quantitative analysts view these things as subjective judgments, and instead focus on the incontrovertible objective data that can be analyzed.

In recent years as computers have been used to do a lot of number crunching, many quants, as they like to call themselves, have gone completely native and will only buy and sell companies on a purely quantitative basis, without regard for the actual business or the current valuation a radical departure from fundamental analysis. Quants will often mix in ideas like a stocks relative strength, a measure of how well the stock has performed relative to the market as a whole. Many investors believe that if they just find the right kinds of numbers, they can always find winning investments.

Company Size. Some investors purposefully narrow their range of investments to only companies of a certain size, measured either by market capitalization or by revenues. The most common way to do this is to break up companies by market capitalization and call them micro-caps, small-caps, mid-caps, and large-caps, with cap being short for capitalization. Different-size companies have shown different returns over time, with the returns being higher the smaller the company. Others believe that because a companys market capitalization is as much a factor of the markets excitement about the company as it is the size, revenues are a much better way to break up the company universe. Although there is no set breakdown used by all investors, most distinctions look something like this:

MICRO — $100 million or less

SMALL — $100 million to $500 million

MID — $500 million to $5 billion

LARGE — $5 billion or more

Arguments Against Quantitative Fundamental Stock Analysis. Because quantitative analysis hinges on screens that anyone can use, as computing horsepower becomes cheaper and cheaper many of the pricing inefficiencies quantitative analysis finds are wiped out soon after they are discovered. If a particular screen has generated 40% returns per year and becomes widely known, and if lots of money flows into the companies that the screen identifies, the returns will start to suffer.

As fuzzy as fundamental analysis might be, there are often times that knowing even a little about the company you are buying can help a lot. For instance, if you are using a high-relative-strength screen, you should always check and see if the companies you find have risen in price because of a merger or an acquisition. If this is the case, then the price will probably stay right where it is, even if the screen you used to pick this company has generated high annual returns in the past. All Stocknod fundamental and technical analysis filters this fuzzy data which allows pinpointed buy and entry signals for any market.

Stock Technical Analysis — What would you do if you truly believed that all information about publicly traded companies was efficiently distributed and that nobody could get an edge on anyone else by either understanding the business or analyzing the numbers? You might consider simply giving up on beating the markets returns by buying an index fund. Some investors have taken an alternate route to find this technical stock analysis. There are several technical analysis software programs available, but all require a steep learning curve and long hours of tedious homework.