European Sovereign Debt Crisis Causes

Post on: 16 Март, 2015 No Comment

Highlights

- The Maastricht accords required low debt levels that euro-area countries ignored.

- Germany buckled down with its own reforms, while other countries had a party.

- Troubled countries regard Germany’s austerity measures as bitter medicine.

Banking » European Sovereign Debt Crisis Causes

European debt crisis

Video

In a nutshell, the European sovereign debt crisis is the result of three separate but interrelated plots: crushing levels of government debt in some countries, problems in the banking sector and the slow growth in Europe. Tying them up in a neat bow is the fact that the euro-area countries are yoked together by a common currency, but they have little else in common economically or culturally.

Convergence

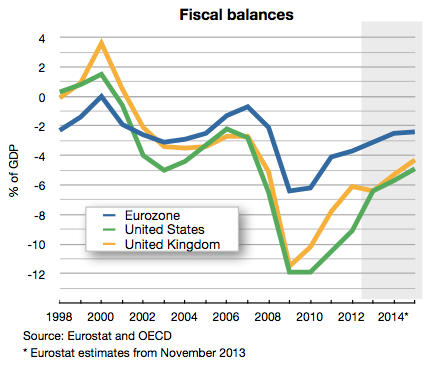

When the monetary union was formed, the countries involved agreed to fiscal requirements called the Maastricht accords, also known as the convergence criteria. The agreement required that government debt not exceed 60 percent of the country’s gross domestic product, or GDP, and that the budget deficit amount to no more than 3 percent of GDP.

They were broken almost immediately, by other countries as well as France and Germany, so people didn’t pay much attention to them, says Michael Klein, professor of international economic affairs at The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University.

Adherence to the convergence criteria is more strictly enforced these days. But the unification under the euro brought some unintended consequences for the individual economies of the euro-area countries since they no longer controlled the fate of their currency.

At the time they joined the euro, they had lost their competitiveness. And this had to do with the fact that they could not devaluate their own currencies any longer as they had been doing over the past 40 or 50 years, says Werner Bonadurer, a clinical professor of finance at the W.P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University.

In 2003, Germany decided to turn everything around within its own country by introducing a series of labor market reforms, known as the Hartz reforms, which were part of a broader reformation known as Agenda 2010. The reforms resulted in very competitive labor costs, and welfare benefits were cut.

Now, if you compare the growth rate of input costs, labor costs in Germany over the last 10 years, with the labor cost increases in southern Europe, the fact is labor costs in Germany barely increased maybe 10 percent over 10 years, while some of Europe had labor cost increases to the tune of about 120 percent, says Bonadurer.

While Germany remodeled its economy, other countries enjoyed the benefits of living under one currency — and received oodles of easy credit.

That came from a quirk of banking regulation that gave bonds issued by governments a zero-risk weighting. Bonds issued in foreign currencies by governments with a certain credit rating or above were viewed as risk-free. Sovereign debt issued in the bank’s own currency wasn’t subject to a credit rating threshold. So French banks could buy lots of Greek bonds for a little extra yield and count them as risk-free.

Banking regulations also allow financial institutions to count risk-free investments, such as sovereign debt, as part of their required liquidity, or available cash.

In 2009 when the full extent of the problems in Greece came to light, banks all over Europe that had bought piles of Greek debt suddenly had a lot less liquidity and began having trouble finding credit. In Spain and Ireland, the banking problems were compounded by bursting housing bubbles.

There’s a real estate crisis in Spain, so you have very high unemployment now because of the collapse of the construction sector, Klein says. In Ireland, there’s a real estate bust as well, and that imperiled a lot of banks and the government was put in a bad situation because the way the government raised revenues was through turnover taxes. When you sold a house you paid a tax and since the real estate market was so active, they got a lot of revenue from that. With the advent of the real estate bust, that source of revenue dried up.

Greece had deep structural problems that were hidden by the economic growth but when that dissolved, they became very apparent, he says. High levels of debt, low levels of tax compliance and government largesse combined to bring an end to the party in Greece.

By late 2009, Greek debt had ballooned to 113 percent of GDP. Once the credit rating agencies began downgrading Greece, their borrowing costs soared and the Greeks quickly found themselves unable to pay the interest rate on the debt. The bailouts followed.

Saving the irreversible euro

As Germany has the strongest economy in the euro area, it’s largely been footing the bill for the bailouts, much to the unhappiness of German taxpayers. For countries that need bailouts, such as Greece, the three official creditors — the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the International Monetary Fund — have budgetary requirements that must be satisfied before they’ll fork over a loan. Their requirements are known as austerity measures and call for government spending and entitlements to be slashed.

As a consequence, no one is very happy. In fact, it remains to be seen if Greece will even meet the budget requirements to qualify for the next loan payment. Its economy is under siege by a deep recession and high unemployment — in excess of 25 percent. In late October, amid low expectations for success, it was rumored that the three creditors — the IMF, the ECB and the European Commission — were in the process of cutting a deal with Greece that would give the country two more years to hit budget targets. The official report from the troika is due in the first half of November.

The only way forward, according to the European Commission, is for the 17 euro-area countries to become more closely connected with a single banking supervisor for all the banks in the region and a real fiscal union.

Knowing the history of Europe, whether the Italians will ever agree to somebody in Brussels determining their tax rates and their budget deficits and their retirement programs, I don’t know, says William R. Gruver, the Howard I. Scott Clinical Professor of Global Commerce, Strategy and Leadership at Bucknell University in Lewisburg, Pa. There is great national pride and there are different languages and so on. But that is the challenge.